The Applied Economics Clinic (AEC) report titled ”A Community Assessment of Health Impacts from the Pittsfield Generating Facility on Local Communities”, prepared on behalf of the Massachusetts Clean Peak Coalition has to be in the running for the most egregious example of inflammatory peaker power plant fear-mongering of all time. This post compares the claims against reality.

I am an air pollution meteorologist and have studied the relationship between atmospheric conditions and air pollution for nearly 50 years. My background in air pollution control theory, implementation, and extensive personal experience with peaking power plants and their role during high energy demand days is particularly well-suited to this topic. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

Environmental non-governmental organizations have latched onto peaking power plants as an example of power company greed and disregard for neighboring communities. For example, the PEAK coalition has stated that “Fossil peaker plants in New York City are perhaps the most egregious energy-related example of what environmental injustice means today.” The influence of this position on current environmental policy has led to this issue finding its way into multiple environmental initiatives. However, I have found that the presumption of egregious harm is based on selective choice of metrics, poor understanding of air quality health impacts, and ignorance of air quality trends. The AEC report takes the claims to ridiculous levels.

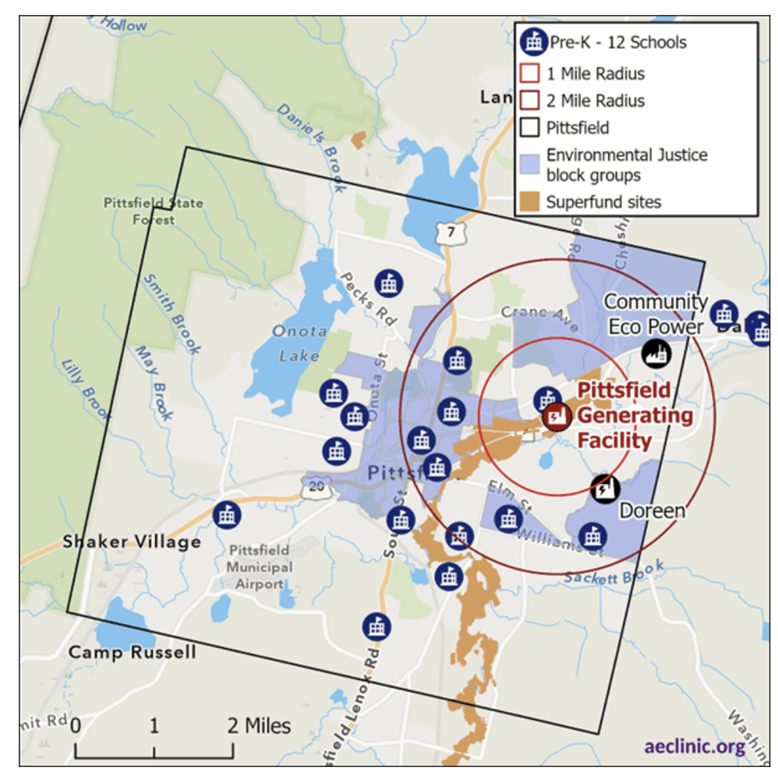

The AEC report example is extreme even compared to the Peak coalition accusations. Researcher Jordan Burt, Assistant Researcher Elisabeth Seliga, Researcher Tanya Stasio, PhD, Research Assistant Lila McNamee, and Principal Economist Liz Stanton, PhD, prepared a report that summarizes the negative health impacts of fossil fuel-fired emissions on communities living near the Pittsfield Generating Facility (Figure 1). They claim that the facility exacerbates negative health outcomes of overburdened residents and asserts there are three key takeaways:

- First, as long as the Pittsfield Generating Facility is in operation, it has the potential to produce much higher greenhouse gas emissions and co-pollutants in any given year.

- Second, Pittsfield’s vulnerable populations live in close proximity to the Facility, putting them at a disproportionate risk for the negative health impacts associated with fossil fuel-fired generation.

- Lastly, replacing the Facility with clean energy resources can not only improve the health outcomes for residents, but also aid the Commonwealth in achieving its decarbonization goals.

Figure 1: Pittsfield Generating Station in Relative to Pittsfield, MA

This article addresses these takeaways.

Pittsfield Generating Company

According to the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) Final Operating Permit Renewal for the facility:

The Pittsfield Generating Company LP is an electric power generation facility located at 235 Merrill Road in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The facility largely consists of three (3) General Electric (GE) Frame 6 6001B combustion turbines, known as Emission Units (EU) – 1, 2, and 3, which are each equipped with steam injection and a selective catalytic reduction system for control of nitrogen oxides (NOX) emissions. Each combustion turbine has a maximum heat input rate of 430.25 million British thermal units per hour (“MMBtu/hr”) and is exhausted to an associated Deltak heat recovery steam generator (“HRSG”). The steam generated in the three (3) heat recovery steam generators is combined to supply a single (1) GE steam turbine. Emission Units 1, 2, and 3 burn natural gas or #2 fuel oil and operate in combined-cycle mode with a net total output of nominally 165-megawatts.

A common claim about peaking power plants is that they are old, dirty, and inefficient units, but these units are modern, well-controlled, and efficient generating units. Despite their efficiency, in the last seven years the units have only run less than 10% of the time which qualifies them to be peaking units. By definition, for EPA reporting purposes 40 CFR Part 75 §72.2, a combustion unit is a peaking unit if it has an average annual capacity factor of 10.0 percent or less over the past three years and an annual capacity factor of 20.0 percent or less in each of those three years. Note that because peaking plants run so little the units can be designed for that mode of operation. The specifications for those units are primarily focus on costs. The Pittsfield units include all the pollution control equipment associated with units designed to run as much as possible. They became peaking units because of market conditions that priced them out of the market, so they simply run less. Nonetheless, they serve an important reliability role providing dispatchable power when needed on high energy demand days.

Takeaway 1

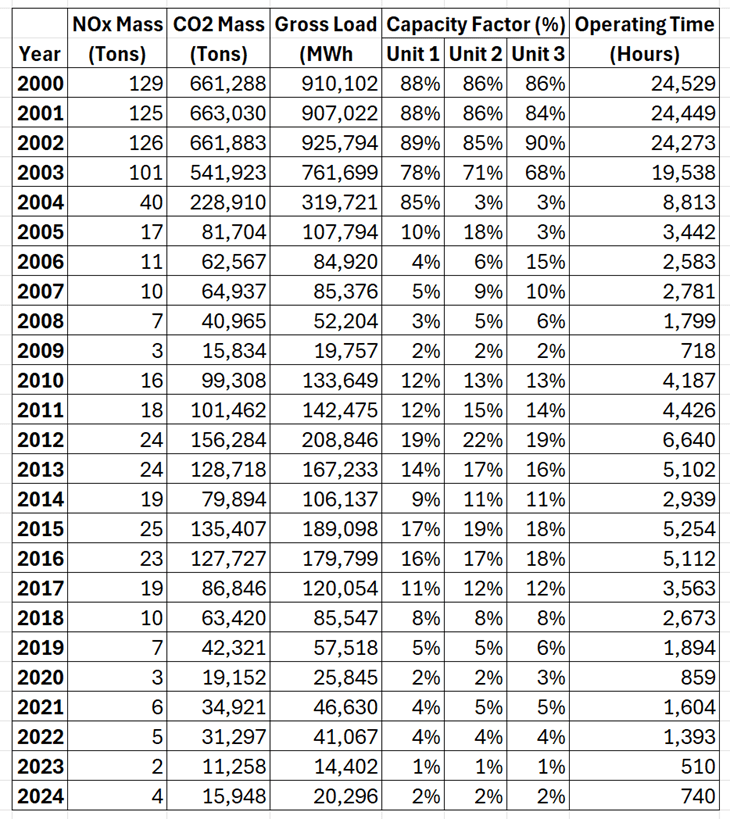

AEC claims that the facility has the potential to produce much higher greenhouse gas emissions and co-pollutants in the future. Table 1 lists the annual emissions and operating information for the last 25 years from the EPA Clean Air Markets Division website. That potential may exist but the historical data show that there has been vast operating and emission reductions since 2000. As a result, any alleged impacts from the facility should have improved significantly over time.

Table 1: Pittsfield Generating Company Facility Emissions and Operating Parameters

Takeaway 2

In the second takeaway AEC states that Pittsfield’s vulnerable populations live near the Facility, putting them at a disproportionate risk for the negative health impacts associated with fossil fuel-fired generation. They offer no estimates of the potential health impacts.

Last year I published a detailed critique of a General Accounting Office (GAO) report “Information from Peak Demand Power Plants” that discussed air quality impact evaluation. The fundamental air quality presumption has always been that the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) is the primary metric used to determine health impacts. As an air pollution meteorologist one of my jobs was to run air quality models to determine the air quality impacts of existing and proposed facilities. The essential consideration was whether the modeling proved that the projected impacts from a facility were less than the NAAQS limits. Industry and regulatory agencies believed that when an applicant showed compliance with those standards, they proved that they were protecting the health of “sensitive” populations such as asthmatics, children, and the elderly. Regulatory agencies are required to ensure that any facility that cannot show compliance with the NAAQS must modify its permitted operations, or it cannot be allowed to operate. The Massachusetts DEP only issues air permits if they are confident that the facility attains the NAAQS, so I am sure that Pittsfield Generating meets those standards.

The air quality pollutant of concern is nitrogen oxides or NOx. The DEP set an emission limit of 22.8 lb NOx/hr. I calculated the average hourly emission using the total NOx mass and the operating hours as 10.4 lb NOx/hr. This is well below the emission rate that we know attains the NAAQS. It is beyond the scope of this analysis and my presently available computer capabilities to quantify specific NOx impacts. However, I only recall doing impacts assessment of power plants that used tons per hour not pounds per hour for an emission rate. My point is that a pounds per hour rate is extraordinarily small and my experience suggests that local impacts at those levels would be so low that they would be difficult to measure and if they cannot be measured there is little chance of any health impact.

Takeaway 3

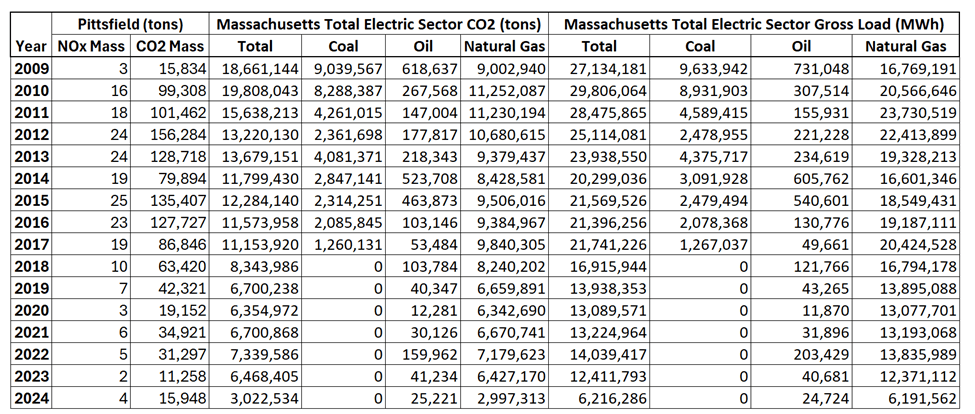

AEC asserts that “replacing the Facility with clean energy resources can not only improve the health outcomes for residents but also aid the Commonwealth in achieving its decarbonization goals.” Environmental justice organizations will read this without understanding the background. In context, the impacts of this facility are well within the NAAQS, probably could not be measured, and the carbon emissions are a negligible fraction of the state total (Table 2). In the last five years the CO2 emissions have been less than or equal to 0.5% of the state total.

Table 2: Pittsfield Emissions Relative to Total Massachusetts Emissions and Operating Characteristics

This table brings up other questions. In New York the coal and oil generation was displaced to natural gas, but the overall Massachusetts generation has dropped significantly while there was a shift away from coal and oil. The Massachusetts CO2 reduction from 2009 to 2023 was 84% while New York only dropped 38%. I do not know why they managed such a substantial decrease.

Pragmatic Concerns

Pragmatic environmentalism is all about tradeoffs. There is no question that disadvantaged communities have suffered and continue to suffer disproportionate environmental impacts, but it is important to understand what causes the harm, balance expectations, and determine potential solutions.

In this instance, it is likely that transportation sources have a bigger impact on air quality for Pittsfield’s vulnerable population. There are just under 44,000 residents in the city, there are 19,566 households, and the average number of cars per household is 2. I assume the estimated 39,132 cars drive two thirds of the Massachusetts average 12,117 miles per year within the city and that means that city mile traveled equals 316,108,296 miles per year. The estimated U.S. average vehicle NOx emission rate per automobile in 2023 was 0.00129 lb. per mile. The result is that in 2023 automobiles emitted 204 tons of NOx. That is more than double the annual emissions from the power plant since 2003 and 57 times higher than the 2024 emissions from the power plant. In addition, auto emissions are close to the ground while the power plant emissions are from elevated stacks so the auto emissions have a greater impact. Clearly, the vilification of the emissions from the power plant is unwarranted.

AEC proposes that the plant be replaced with an “alternative, cleaner energy source like a solar plus storage facility can help reduce community exposure to pollution”. The Title V permit says that emission units 1, 2, and 3 have a “net total output of nominally 165-megawatts.” I estimate that 165MW of solar would cover 973 acres. However, to ensure reliable reinforcement of a gas plant requires more than a one for one replacement. Based on this reference, the solar required would be 660 MW covering 3,894 acres. The storage system may need to be oversized as well, potentially requiring 410 MW of 4-hour storage to replace 100 MW of gas peaker capacity. Replacing perfectly good power plant with solar plus storage prematurely does not seem to be a good investment.

AEC claims that the solar plus storage option would reduce exposure to pollution. However, there are substantive safety concerns with currently available battery energy storage systems. On January 16, 2025 a fire was reported at the Vistra Moss Landing Energy Storage Facility located in Moss Landing, California. The fire burned at a temperature of between 2500 – 5000 degrees Fahrenheit. Since the fire heavy metals have been measured at levels 100 to 1,000 times higher than normal in soil within a mile of the facility. During the fire there was an evacuation zone within 1.5 miles of the facility. In my opinion, the risks of environmental impacts from a battery fire far outweigh the “benefits” of eliminating the minimal emissions of this facility.

Moreover, there is no currently available technology that has been proven at the scale necessary that can replace fossil-fired generation safely, reliably, and affordably. If those characterized are not prioritized, then it could easily result in an electric system that does not maintain current standards. More importantly, problems associated with reliability impact disadvantaged communities most so those concerns must be considered when decisions are made about peaking power plants benefits and potential impacts.

Conclusion

This analysis epitomizes my frustration with pragmatic tradeoffs for peaking power plants. AEC claims that the facility has the potential to produce much higher greenhouse gas emissions and co-pollutants in the future ignoring the fact that emissions have gone down significantly since the plant started operating. AEC also claims that Pittsfield’s vulnerable populations live near the Facility, putting them at a disproportionate risk for the negative health impacts associated with fossil fuel-fired generation. AEC overlooks the fact that facility emissions are so small that adverse health impacts are unlikely from the plant and that transportation emissions are much higher which means adverse air quality impacts are more likely from other sources. AEC’s final takeaway claim is that “replacing the Facility with clean energy resources can not only improve the health outcomes for residents but also aid the Commonwealth in achieving its decarbonization goals.” That is true in theory, but it ignores the fact that there are other emission reduction strategies that are likely to be more effective and pose less risk to the electric system than shutting down a dispatchable generating resource. Fear mongering based on emotion and not facts is not in the best interests of a reliable electric system and this report is the best example of this folly I have seen to date.