For the first two months of 2024 the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and the New York Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) have been working on the New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) Program stakeholder engagement process. As part of the stakeholder engagement process there was a webinar describing the Preliminary Scenario Analyses. One thing that caught my attention was the claim that health benefits could be as much as $15.7 billion in 2035 because of NYCI implementation.

Two recent blog posts described a literature article about the development of the Linear No Threshold (LNT) model for cancer risk that is the basis of the NYCI health benefits claim. This post describes the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene paper by Edward Calabrese “Cancer risk assessment, its wretched history and what it means for public health” and the NYCI health benefits claims.

I have followed the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 400 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. It includes an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% reduction by 2030 and a requirement that all electricity generated be “zero-emissions” by 2040. The Climate Action Council (CAC) is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlines how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” In brief, that plan is to electrify everything possible using zero-emissions electricity. The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to develop the Draft Scoping Plan outline of strategies. After a year-long review, the Scoping Plan was finalized at the end of 2022. In 2023 the Scoping Plan recommendations were supposed to be implemented through regulation, PSC orders, and legislation. Not surprisingly, the aspirational schedule of the Climate Act has proven to be more difficult to implement than planned. NYSERDA and DEC are attempting to promulgate rules for NYCI so that the program starts in 2025 and the regulatory package will claim significant health impacts that I think are unjustified.

Linear No Threshold Model

The weekly newsletter “The Week That Was: 2024-03-23” produced by the Science and Environmental Policy Project includes a section titled “Lack of Science Integrity” that describes the Edward Calabrese “Cancer risk assessment, its wretched history and what it means for public health” paper. That post walks the reader through the paper with extensive quotes including the introduction:

The story about to unfold in this commentary will be disturbing but perhaps not too surprising now in contemporary society. You will be taken on a path of discovery that explores the history of cancer risk assessment for radiation and chemical carcinogens. This commentary is about a history of errors made by scientific leaders that have long remained hidden and uncorrected. The evidence shows that major biases led to deliberate misrepresentations (i.e., blatant dishonesties) of the scientific record by the very people society was supposed to trust, including multiple Nobel Prize winners. Equally troubling have been the dishonest actions of organizations, such as major advisory bodies, including the US NAS and the journal Science that have repeatedly succumbed to violations of the public trust. As disappointing and upsetting as such statements are, it is hard to believe that this historical record could get even more corrupt, but it does. It has become known that major US scientists conducting important mutation and cancer studies hid data and deliberately withheld results from the public and scientific community. Why? Because the findings didn’t fit their preconceived beliefs and would not enhance opportunities to obtain more funding for themselves and their programs. Yes, the destructive self-interest of the research community, especially governmental and university scientists, in this case, presents a prominent but long hidden dimension that unfolds in a complex journey of discovery.

Society is faced with questions over who can be trusted in today’s world: government, scientists, prestigious advisory groups, like the United States National Academy of Sciences (US NAS), and major journals like Science, Nature, The Lancet, and others. These have historically all been the entities that society has trusted for decades. The historical record presented here, therefore, involves powerful and high-profile individuals and groups that manipulated the public for personal gain and is presented in the following eight-part expose.

If you are interested, then I encourage you to read the rest of the SEPP newsletter and the article itself but the implications are not immediately obvious without background. Originally, I thought I would use this post as the basis for describing the background of problems identified in the Calabrese paper. However, Francis Menton wrote a post doing just what I was planning to do.

Menton notes that:

Calabrese’s article is long (18 two-column single-space pages) and goes into detail of the names involved, the particular pieces of evidence suppressed along the way, the manipulation of members of committees to get to desired outcomes, and so forth. It has a lengthy bibliography, including references to multiple prior articles of his own where he has been piecing together and building the story of the LNT fraud for years. If you are interested in this subject, I highly recommend this article.

Menton argues that this approach is a candidate for the greatest scientific fraud of all time. He writes:

This fraud goes by the common acronym of “LNT,” which stands for the “linear no threshold” hypothesis of causation of diseases, particularly cancer, from environmental factors. The LNT hypothesis is the basis for huge swaths of enormously costly regulation, probably the large majority of environmental regulatory cost outside the sphere of “climate.” In a March 7 article in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, a guy named Edward Calabrese makes the case that the LNT hypothesis has been advanced by means of intentional fraud since its inception nearly 100 years ago. The title of the article is “Cancer risk assessment, its wretched history and what it means for public health.”

He describes the basis of the approach:

The LNT hypothesis theorizes that if a chemical or phenomenon (e.g., radiation) is established as dangerous at some dosage, no matter how high, then it must also be dangerous at small dosages, no matter how tiny. That conclusion follows if the relation of dose to danger is linear, with no threshold below which the danger goes away. A tiny dose may have a tiny danger, but as long as the dose/danger relationship is linear without threshold, then there is no safe dose.

This approach was originally developed to address cancer risk from nuclear radiation exposure, but the principle is now applied in other ways.

Calabrese’s article provides a thorough history of the origins of the LNT hypothesis, and how it was advanced and promoted by the suppression of definitive contrary evidence. By the 1970s the LNT hypothesis had the backing of the National Academy of Sciences and had been adopted by the EPA as the basis for regulating hazardous chemicals and radiation. The EPA continues to use the LNT approach in its regulatory efforts today, even as evidence accumulates that it is wrong and has been based on fraud from the outset. And thus, the LNT hypothesis is the fundamental reason why nuclear power plants are so expensive and difficult to build; why no long-term solution for storage of spent nuclear fuel can be found; why EPA constantly proposes new regulations lowering allowable levels of emissions of chemical substances like mercury or PCBs; why pesticides and herbicides like glyphosate become the subject of multi-billion dollar liability disasters; and so forth.

Menton goes on to explain:

The LNT hypothesis may at first seem intuitively likely to be true. For example, it is established that large doses of radiation can induce mutations that can lead to cancer. So why then couldn’t a single item of radiation, like one alpha particle or a single gamma ray, induce the mutation that initiates the disease? But Calabrese points out that the LNT hypothesis presumes that mutations are rare, and that the body has no capacity to repair ongoing mutations. What research has revealed is that, far from being rare, mutations are extremely common; and the body has a large capacity to repair them. Thus, a small external source of mutations, like background or low-dose radiation, is easily dealt with, and if anything helps to stimulate and exercise the body’s natural repair system. Only when an external force causes very extensive mutations exceeding the body’s capacity to repair — i.e., when some threshold is crossed — does the external force increase the risk of cancer or other disease. From Calabrese, page 16:

[T]he most dominating cause of evolution is our metabolism which induces millions of mutations per day in each cell, with 99.99999% being repaired each day. If our repair systems were not so exceptionally good, life would not exist. Our metabolism produces about 200 million times more genetic damage events per cell per day than that induced by background radiation. There is no contest between the two. What this means is that our body is our biggest enemy; it also means that it is also our best friend. The body’s great repair mechanisms evolved not to prevent and repair damage from background radiation but to fix the damage that our metabolism induces each day. Thus, the body’s repair systems are designed by nature to protect our bodies against ourselves, with background radiation being a very tiny and insignificant factor.

Sadly, this approach is widely used and now provides “justification” for many environmental regulations. Proponents calculate a relationship between health effects at two high levels then extrapolate the dose response curve to ridiculously low levels. Even though there is a tiny effect multiplying the impact over a large population provides scary projections for things like asthma exacerbation. Menton explains why it has become so pervasive.

So how did the LNT hypothesis gain such enormous sway, and become the basis for extensive and destructive government decision-making for decades? Calabrese points out that, by contrast to the threshold hypothesis, the LNT hypothesis has the potential to induce great fear in the public, and thus to stimulate large opportunities for funding and career advancement:

[T]he experts got the radiation and chemical mutation idea wrong from the start but they convinced many that they were correct and created debilitating fear in the population at the same time. We also learned that one of the reasons that these great scientists created such fears was to advance their careers and to get a constant flow of government grant monies.

In the next section I will show how NYSERDA and DEC have used this approach for NYCI. Menton provides a good segue to that section:

Meanwhile, our government and its “experts” merrily go forth regulating on the basis of the LNT hypothesis, and imposing enormous costs on society for no benefit. From Calabrese’s Conclusion:

[The scientists who promoted the LNT hypothesis] were driven by ideological and self-serving professional biases that would lead to both falsifications of the research record and suppression of key scientific findings, all to establish the LNT model for hereditary and cancer risk assessment, replacing the threshold dose-response model. This troubling history has now been revealed in a long series of peer-reviewed publications by the author and summarized in a broad conversational manner in this Commentary. This troubling history remained hidden from regulatory agencies around the globe since its inception. These groups simply and uncritically accepted a flawed and corrupt history, assuming that it was accurate and reliable. Yet this path of historical ignorance led the US EPA, and other national regulatory agencies, to accept a dishonest foundation upon which to base and frame cancer risk assessment, terribly failing in their public service mission.

New York Cap and Invest Health Impacts

The purpose of this article is to show the basis for the projected health effects of NYCI. At the January 26, 2024 webinar the methodology for the health effects was described. In brief, fuel consumption changes by sector projected by their modeling were used to estimate changes in emissions. The changes in emissions reduce ambient air quality levels and this leads to the alleged health benefit improvements. Because the emissions estimates cannot be broken down into detail the air quality impacts also are broad estimates. EPA’s CO-Benefits Risk Assessment Health Impacts Screening and Mapping Tool uses the LNT approach to estimate health impacts, primarily for improvements in inhalable particulate matter that is 2.5 microns or smaller.

The projected health impacts description claims that there are substantial benefits.

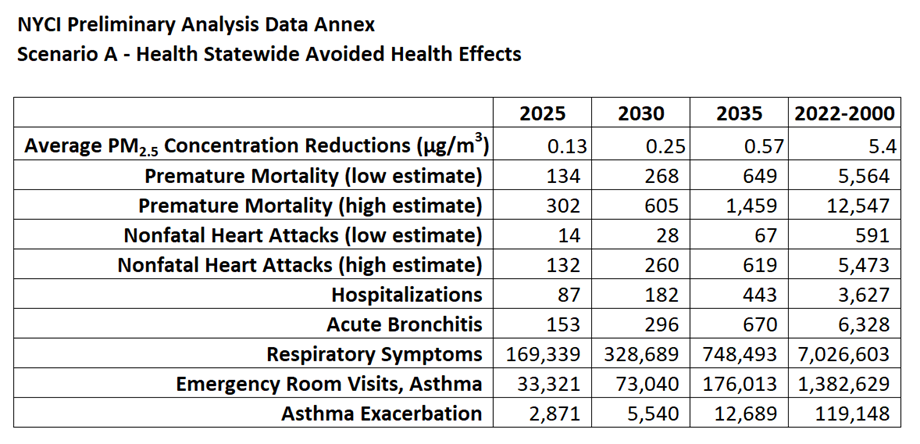

The NYCI Preliminary Analysis Data Annex spreadsheet includes supplementary health effects data for the webinar presentation and a table that estimates impacts on air quality and health. The following table excerpts some of the health benefits projections. Frankly, I think that all these improvements are well within normal variation so the whole exercise has little value. Note that I expected that each of the benefits would be linearly proportional to the change in concentrations but applying the ratio of 2025 to 2030 improved concentrations to the health benefits did not match exactly. In all cases the assumed proportional benefit was less than the benefits shown.

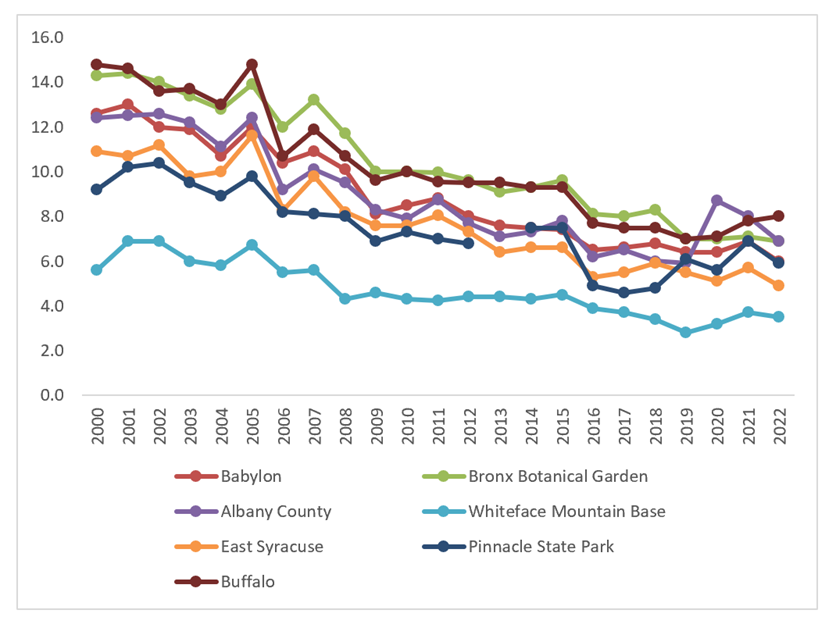

Despite the lack of an exact linear match, I believe the results are close enough to use them to project health benefits between the inhalable particulate concentrations in 2000 relative to 2022. The Department of Environmental Conservation runs a network of inhalable particulate monitoring stations across the state and summarizes the results in its Ambient Air Quality Reports. I extracted the annual average concentrations for seven widely ranged sites with the longest records. All the stations show significant improvements in the inhalable concentrations over the period of record. I calculated the average of these sites in 2000 11.4 micro grams per cubic meter and 2022 6.0 micro grams per cubic meter for a statewide improvement of 5.4.

New York State Annual Average Inhalable Particulate Air Quality (micro grams per cubic meter) Trend

The following table compares the observed improvement in air quality and projects health benefit improvements proportional to the change in inhalable particulates. If there has been an observed reduction of over one million emergency room visits for asthma between 2000 and 2022 then I will believe the NYCI health benefit projections. I have never seen anyone verify this health benefit model which should be easy to do. I expect that the results would be inconvenient, and proponents of this methodology know this so it has never been done.

Conclusion

In every instance I have checked the Hochul Administration has overstated the benefits and understated the costs of the net-zero transition. New York’s cap-and-invest projected health benefits are a vivid example of how NYSERDA manipulates the narrative to claim benefits that far exceed any reasonable interpretation. I think Menton’s conclusion is an appropriate: “As of today, there is no evident retreat by EPA or other U.S. regulatory agencies from the LNT model. Fear sells, and they have no ability or incentive to self-correct.”