I have regularly prepared updates on the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) annual Investments of Proceeds report. Last year I combined the update with lessons to be learned concerning the relative emission reduction effectiveness of the different investments categories used in the reports. This post updates my past summaries and summarizes the implications relative to the recently completed Third Program Review.

Dealing with the RGGI regulatory and political landscapes is challenging enough that affected entities seldom see value in speaking out about fundamental issues associated with the program. I have been involved in the RGGI program process since its inception and have no such restrictions when writing about the details of the RGGI program. I have worked on every cap-and-trade program affecting electric generating facilities in New York including RGGI, the Acid Rain Program, and several Nitrogen Oxide programs, since the inception of those programs. I also participated in RGGI Auction 41 successfully winning allowances and holding them for several years. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

RGGI is a market-based program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) (Factsheet). It has been a cooperative effort among the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont to cap and reduce CO2 emissions from the power sector since 2008. New Jersey was in at the beginning, dropped out for years, and re-joined in 2020. Virginia joined in 2021 but has since withdrawn, and Pennsylvania has joined but is not actively participating in auctions due to on-going litigation. According to a RGGI website:

The RGGI states issue CO2 allowances that are distributed almost entirely through regional auctions, resulting in proceeds for reinvestment in strategic energy and consumer programs.

Proceeds were invested in programs including energy efficiency, clean and renewable energy, beneficial electrification, greenhouse gas abatement and climate change adaptation, and direct bill assistance. Energy efficiency continued to receive the largest share of investments.

Despite claims about the success of RGGI, the reality is that the only thing it is good at is raising money. Suggestions that RGGI has been responsible for the observed reductions in CO2 emissions over the life of the program ignore the importance of fuel switching and the poor performance of RGGI auction proceed investments in reducing emissions. I document these observations below.

Proceeds Investment Report

The 2023 investment proceeds report was released on July 16, 2025. According to the press release: “In 2023, $852 million in RGGI proceeds were invested in programs including energy efficiency, clean and renewable energy, beneficial electrification, greenhouse gas abatement, and direct bill assistance. Over their lifetime, these 2023 investments are projected to provide participating households and businesses with $2.7 billion in energy bill savings and avoid the emission of 7.8 million short tons of CO2.” The report breaks down the investments into major categories. The 2023 investment report explains:

Energy efficiency makes up 64% of 2023 RGGI investments and 56% of cumulative investments. Programs funded by these investments in 2023 are expected to return about $1.9 billion in lifetime energy bill savings to more than 181,000 participating households and 1,083 businesses in the region and avoid the release of 5.3 million short tons of CO2.

Clean and renewable energy makes up 6% of 2023 RGGI investments and 12% of cumulative investments. RGGI investments in these technologies in 2023 are expected to return over $647 million in lifetime energy bill savings and avoid the release of more than 1.9 million short tons of CO2.

Beneficial electrification makes up 9% of 2023 RGGI investments 4% of cumulative investments. RGGI investments in beneficial electrification in 2023 are expected to avoid the release of 436,000 short tons of CO2 and return over $94 million in lifetime savings.

Greenhouse gas abatement and climate change adaptation makes up 2% of 2023 RGGI investments and 7% of cumulative investments. RGGI investments in greenhouse gas (GHG) abatement and climate change adaptation (CCA) in 2023 are expected to avoid the release of more than 49,000 short tons of CO2.

Direct bill assistance makes up 15% of 2023 RGGI investments and 15% of cumulative investments. Direct bill assistance programs funded through RGGI in 2023 have returned over $128 million in credits or assistance to consumers.

This official story about the virtues of RGGI investments does not square with reality.

Emission Reductions

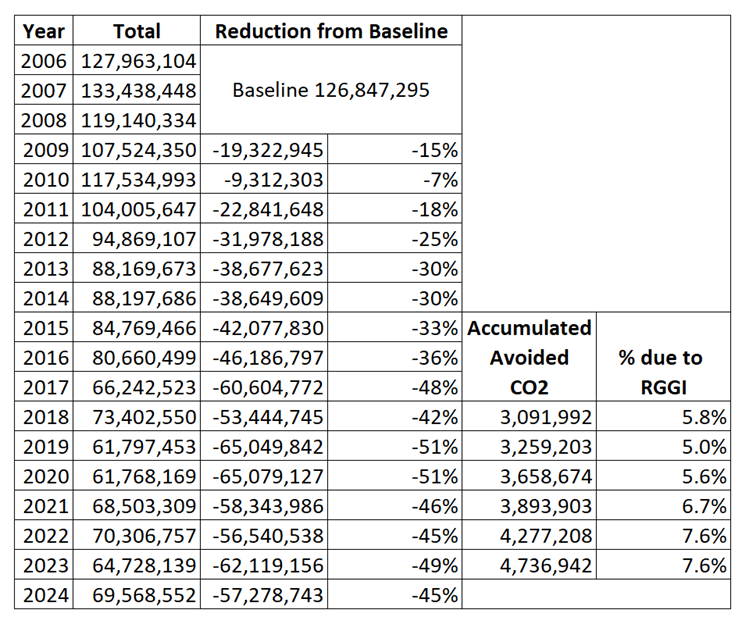

All my summaries of the RGGI Investment Proceeds reports have found the same results. Since the beginning of the RGGI program, RGGI funded control programs have been responsible for a small fraction of the observed reductions – only 7.6% in 2023 (Table 1). The primary reason for the observed reductions has been fuel switching away from coal and oil to natural gas. Importantly, the availability of potential fuel switching in the RGGI fleet of electric generating units is running out. Consequently, future reductions will have to rely on the deployment of zero-emission generating resources and load reductions which makes cost-effective emission investments important.

Table 1: State-Level CO2 Emissions for Nine RGGI States 2009 to 2024

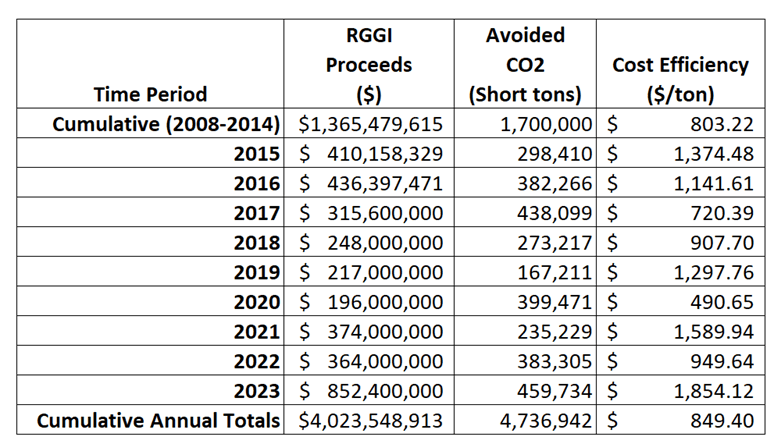

The importance of cost-effective investments for emission reductions is unacknowledged. I calculate cost effectiveness by dividing the RGGI total investments divided by the estimated avoided CO2 emissions. In 2022 the CO2 emission reduction efficiency was $949 per ton of CO2 reduced but in 2023 the cost per ton reduced increased to $1,854. Because there is no obvious change in investment strategies, I think the differences are due to changes in the calculation methodology. This cannot be confirmed because there is insufficient documentation.

Table 2: Accumulated Annual RGGI Proceeds, Avoided CO2, and Cost Efficiency

Emission Reduction Costs

RGGI is supposed to be an emissions reduction program. On July 3, 2025, RGGI announced the results of the Third Program Review that modified the requirements for future reductions. Based on my analysis of the planned revisions, the RGGI States only delayed the inevitable reckoning of the futility of this program to achieve the goal of a “zero-emissions” electric system. The RGGI summary of the revisions states that the revised mandated reductions will “decline by an average of 8,538,789 tons per year, which is approximately 10.5% of the 2025 budget” from 2027 to 2033.

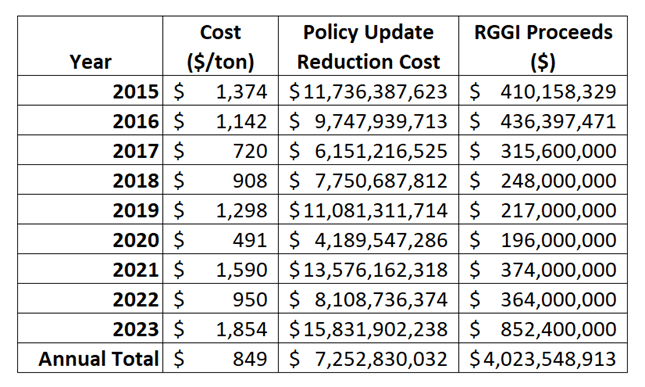

Table 3 lists the cost per ton of CO2 removed of the RGGI investments from 2015 to 2023, the cost to reduce 8,538,789 tons per year using their observed costs, and the RGGI proceeds for each year. In 2023 the Third Program Review mandated annual emission reduction multiplied by the cost per ton ($1,854) totals $15.8 billion but the RGGI proceeds were only $0.85 billion. Even using the cost over the entire period of $849 per ton, it would cost $7.25 billion to make the reductions mandated. This is still far short of the proceeds available.

Table 3: Annual RGGI Cost Efficiency, Cost to Meet 2027 RGGI Annual Reduction, and Annual Proceeds

Investment of Proceeds Summary

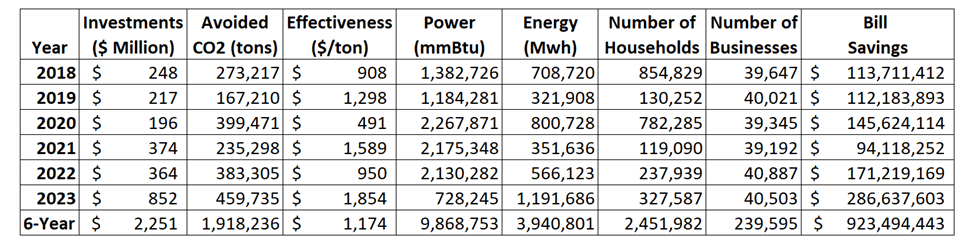

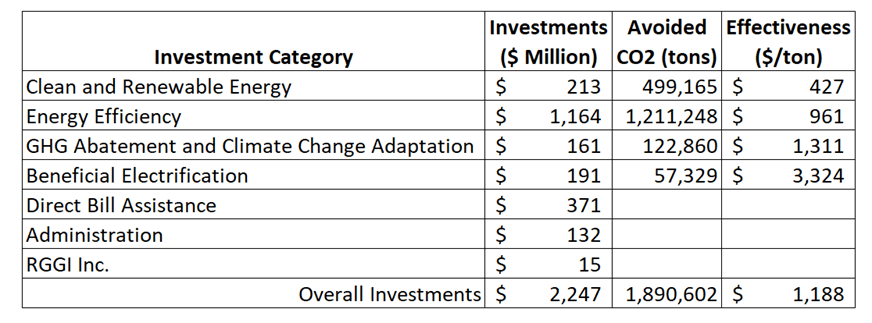

The 2023 investment proceeds report breaks down the investments into major categories. I added the annual values for each category to provide the following summary (Table 4). Note that the overall cost effectiveness is $1,174 per ton avoided. Clearly the proceed investment strategy is not emphasizing emission reduction effectiveness. It is encouraging that savings of $924 million are claimed but total investments are $2,251 million. In my opinion, these numbers are inconsistent with claims that RGGI is successful.

Table 4: RGGI Proceeds Report Investment Category Annual Totals

Cost Effectiveness Implications

One of my big concerns about any cost on carbon emissions is that it is a regressive stealth tax on energy. There is a tradeoff between trying to minimize those impacts and reducing emissions. In the last six years $371 million or 16% of the RGGI auction proceeds went to direct bill assistance, which is good but that means that much less was available to reduce emissions (Table 5). Throw in the $132 million over the last 6 years for administration that means that 23% of the RGGI auction proceeds were not used to reduce emissions.

Table 5: Summary of Recent RGGI Categorial Investments and Avoided Emissions Over the Last 6 Years

This article compares the cost effectiveness of emission reductions for the following investment categories: energy efficiency, clean and renewable energy, beneficial electrification, greenhouse gas abatement and climate change adaptation (Table 3). For the investment categories that provided emission reductions Clean and Renewable Energy was the most effective way to reduce emissions. As far as I can tell this category provides the most funding for projects that directly reduce emissions. It is encouraging that the energy efficiency is right around the average over all categories. This means that energy efficiency programs targeted at low- and middle-income households most affected by this energy tax will provide effective emission reductions but only at a cost near $1,000 per ton.

On the other hand, programs promoting the research and development of GHG abatement and climate change adaptation are less effective at reducing emissions. Perhaps a greater emphasis on programs promoting reduction of emissions in the power generation sector and advanced energy technologies and less emphasis on programs for the reduction of vehicle miles traveled, tree-planting projects designed to increase carbon sequestration, and climate adaptation and community preparedness initiatives would improve emission reduction efforts consistent with the emission reduction goal of RGGI.

The worst emission reduction programs are associated with beneficial electrification that are “designed to reduce fossil fuel consumption by implementing or facilitating fuel-switching to replace direct fossil fuel use with electric power.“ This category was added recently. There are two ways to look at the high numbers. On one hand, it could be that it recognizes that reductions of overall fossil fuel consumption require efforts across all sectors. On the other hand, I think it inappropriately transfers costs to the electric sector that do not provide efficient emission reductions.

Discussion

As noted previously, since the beginning of the RGGI program RGGI funded control programs have been responsible for a small fraction of the observed reductions (e.g., only 7.6% in 2023). The primary reason for the observed reductions has been fuel switching away from coal and oil to natural gas. There are limited opportunities to make further fuel switching changes. Consequently, future reductions will have to rely on the deployment of zero-emission generating resources. This means that compliance with the RGGI emission caps is out of the control of the affected generating units and that RGGI investments must fund much of the reductions needed.

New York’s Value of Carbon guidance estimates that the 2025 cost of carbon at a 2% discount rate is $133.75. Per this guidance, when used for a damages-based approach to valuing greenhouse gas emissions, the value of carbon provides a monetary estimate of the impacts on society from activities that are a source of greenhouse gas emissions. The estimated emission reductions cost per ton removed exceeds that limit for every year and every investment category. This suggests that the emission reduction costs exceed the societal benefits expected.

The ostensible purpose of RGGI is to reduce emissions. In theory the auction proceeds would be invested to facilitate emission reduction programs but categorial investments do not reflect that as a priority. The beneficial electrification category is the worst. It illustrates the tendency for government funding priorities to shift away from the original priorities of the program.

The RGGI funding priorities do not reflect the necessary funding required to meet the annual reduction mandates in the recently approved Third Program Review modifications. Using the future mandated emission reduction and the observed 2023 reduction efficiency (8,538,789 tons multiplied by the cost per ton $1,854) totals $15.8 billion. However, the RGGI proceeds in 2023 were only $0.85 billion. These results show that RGGI investments will not provide the emission reductions mandated. That leaves the question – where will the reductions come from?

Conclusion

These results support my conclusion that RGGI can only claim to raise money effectively. Claims that RGGI is a successful emission reduction program are inconsistent with the following observations. The investment costs exceed the expected societal benefits. The amount raised falls far short of the funds necessary to reduce RGGI emissions in accordance with Third Program Review requirements. Investment priorities are inconsistent with the emission reduction objectives. Finally, emission reductions associated with RGGI investments only account for 7.6% of the observed reductions.

Someday, the shortcomings of the RGGI approach will result in serious problems. When the only compliance option available to generating plants is to reduce operations, then an artificial energy shortage will result.