On January 11, 2021 the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act Power (CLCPA) Generation Advisory Panel met as part of the Climate Action Council Scoping Plan development process. The meeting tested a consensus building process to address the “problem” of peaking power plants. This post addresses that discussion.

On July 18, 2019 New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), which establishes targets for decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing renewable electricity production, and improving energy efficiency. I have written extensively on implementation of the CLCPA closely because its implementation affects my future as a New Yorker. I have described the law in general, evaluated its feasibility, estimated costs, described supporting regulations, listed the scoping plan strategies, summarized some of the meetings and complained that its advocates constantly confuse weather and climate. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

Last summer I wrote that New York State energy and environmental policy is more about optics than facts as exemplified by opinion pieces, reports, and even policy proposals related to peaking power plants in New York City. The perception that they have significant local impacts and have no use in the future has now invaded the CLCPA implementation process.

The optics post summarized three detailed technical posts all related to the PEAK Coalition report entitled: “Dirty Energy, Big Money”. The first post provided information on the primary air quality problem associated with these facilities, the organizations behind the report, the State’s response to date, the underlying issue of environmental justice and addressed the motivation for the analysis. The second post addressed the rationale and feasibility of the proposed plan relative to environmental effects, affordability, and reliability. Finally, I discussed the Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers (PSE) for Healthy Energy report Opportunities for Replacing Peaker Plants with Energy Storage in New York State that provided technical information used by the PEAK Coalition.

In brief, peaking power plants are used to ensure that there is sufficient electricity at the time it is needed most. The problem is that the hot, humid periods that create the need for the most power also are conducive to the formation of ozone. In order to meet this reliability requirement ~ 100 simple cycle turbines were built in New York City in the early 1970’s that were cheap and functional but, compared to today’s standards, emitted a lot of nitrogen oxides that are a precursor to ozone. The Peak Coalition report claims that peaking units operate when energy load spikes, are mostly old, and have high costs. However, they expand the definition of peaking units to just about every facility in the City including units that are new, have low emission rates, and have lower costs than claimed. Environmental Justice advocates claim that the expanded definition peaking power plants are dangers to neighboring environmental justice communities. However, my analyses found that the alleged impacts of the existing peaking power plants over-estimate impact on local communities relative to other sources.

There is a category of existing simple cycle peaking turbines in New York City that are old, inefficient and much dirtier than a new facility and clearly should be replaced. However, they reliably produce affordable power when needed most. PSE and the PEAK Coalition advocate a solar plus energy storage approach and that has become the preferred approach of the majority of the Power Generation Advisory Panel members. It is not clear, however, if that is a viable option.

Peaking Power Plant Status

By definition, for EPA reporting purposes 40 CFR Part 75 §72.2, a combustion unit is a peaking unit if it has an average annual capacity factor of 10.0 percent or less over the past three years and an annual capacity factor of 20.0 percent or less in each of those three years. As noted previously the utility industry considers the combustion turbines built expressly for peak periods as the New York City peaking plants. PSE chose to select peaking power plants based on the following criteria: fuel type: oil & natural gas; Capacity: ≥ 5 MW; capacity factor: ≤15% (3-yr. avg.); unit technology type: simple cycle combustion turbine, steam turbine & internal combustion; application: entire peaker plants & peaking units at larger plants; and status: existing and proposed units.

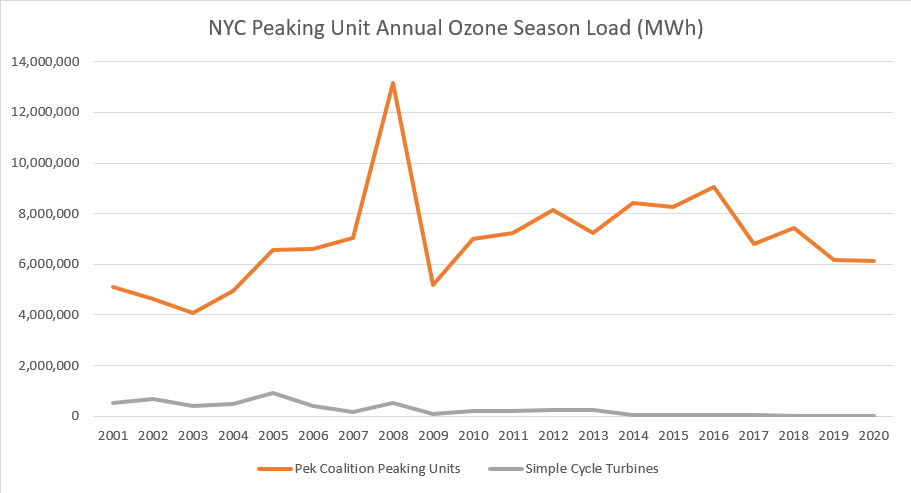

There is another nuance to the peaking units story. Because the primary concern with the combustion turbines that run so little is ozone attainment, they only are required to report data during the Ozone Season (May 1 to September 30). The NYC Peaking Unit Annual Ozone Season Load graph shows the trend of the simple cycle combustion turbine peaking unit and the Peak Coalition peaking unit ozone season load. Since 2001, the simple cycle turbines load trend is down and in 2020 the ozone season total energy produced was only 8,155 MWh compared to a peak over this period of 897,939 MWh in 2005. On the other hand, the Peak Coalition peaking units have only been trending down since 2017. Over that short a period the effects of weather may be the primary driver of any load changes.

The New York City Ozone Season Trends table categorizes the units as simple cycle turbines (the industry “peakers”), all the other turbines, boilers that provide electricity and steam boilers that provide steam. In the last 20 years a number of combined cycle combustion turbines that are more efficient than the simple cycle turbines and the boilers. In 2020, that category provided the most energy of any of the units considered displacing most of the simple cycle turbine output and a big chunk of the boilers producing electricity. As shown in the table, in 2020 the “peakers” only generated 8,155 MWh and emitted 6,927 tons of CO2 and 28 tons of NOx. The combined cycle turbines produced 3,968,562 MWh, 1,772,752 tons of CO2 and 103 tons of NOx and the boilers produced 2,172,185 MWh in 2020, 1,654,514 tons of CO2 and 752 tons of NOx in the 2020 Ozone Season.

Alternatives

I don’t think that many of the members of the power generation advisory panel really understand the electric system. Although the simple cycle turbine peaking units have run less and less, completely eliminating them is still a significant undertaking. Nonetheless, last year the Department of Environmental Conservation promulgated a new regulation that will shut them down on a schedule based on complete assurance that equally reliable options are available. In order to eliminate the units in the Peak Coalition report is a much more difficult problem. Unfortunately, to the ill-informed it is a simply a matter of political will.

The apparent preferred option is to use energy storage ultimately powered using renewables. In December 2020, 74 Power Global and Con Edison announced the signing of a seven-year dispatch rights agreement for the development of a 100-megawatt battery storage project, the East River Energy Storage System, in Astoria, Queens. The NRG Astoria Gas Turbine facility presently consists of 24 16MW simple cycle turbines is also located at the same location. The East River Energy Storage System is rated to provide 4 hours at 100 MW capacity or 400 MWh. On the other hand, those 24 16MW turbines can run all day if the need arises to produce 9,216 MWh or 23 times more energy.

Unfortunately, that is not the end of the bad news for energy storage. Last year I estimated the energy storage requirements of the CLCPA based on a NREL report Life Prediction Model for Grid-Connected Li-ion Battery Energy Storage System that describes an analysis of the life expectancy of lithium-ion energy storage systems. The abstract of the report notes that “The lifetime of these batteries will vary depending on their thermal environment and how they are charged and discharged. To optimal utilization of a battery over its lifetime requires characterization of its performance degradation under different storage and cycling conditions.” The report concludes: “Without active thermal management, 7 years lifetime is possible provided the battery is cycled within a restricted 47% DOD operating range. With active thermal management, 10 years lifetime is possible provided the battery is cycled within a restricted 54% operating range.” If you use the 54% limit the 400 MWh of energy goes down to 216 MWh and the existing turbines can produce over 42 times as much energy in a day.

The mantra of the environmental justice advocates on the power generation advisory panel is that “smart planning” and renewables will be sufficient to replace fossil generation peaking plants. In the absence of what is exactly meant by “smart planning” I assume that it will be similar to the New York Power Authority agreement to “assess how NYPA can transition its natural gas fired ‘peaker’ plants, six located in New York City and one on Long Island with a total capacity of 461 megawatts, to utilize clean energy technologies, such as battery storage and low to zero carbon emission resources and technologies, while continuing to meet the unique electricity reliability and resiliency requirements of New York City.” Beyond the press release however, is a major technological challenge that if done wrong will threaten reliability.

Moreover, the costs for this technology seem to be an afterthought. The Energy Information Administration says the average utility scale battery system runs around $1.5 million per MWh of storage capacity. That works out to $600 million for the East River Energy Storage System. NYC currently peaks at around 13,000 MW– just to keep the city running. I get the impression that one aspect of “smart” planning is to shave peaks but the CLCPA targets will require electrification across all sectors. I don’t think that any peak shaving programs can do much to reduce the current summer peak and the peak will certainly shift to the winter when peak shaving and shifting of heating is unrealistic. Assuming the same peak level and that the daily total peak above the baseline requires 104,000 MWhr, that means that 481 East River Energy Storage Systems operating at the NREL 54% limit would be needed to cover the peak at a cost of $289 billion. Throw in the fact that the life expectancy is ten years and I submit this unaffordable.

NYC Solar

Even if you have enough energy storage, the mandates of the CLCPA require the use of solar and wind resources to provide that energy. There are specific in-city generation requirements for New York City that have been implemented to ensure there is no repeat of blackouts that were caused by issues with the transmission and generation system. It is not clear to me how this will be handled within the CLCPA construct but there is a clear need for in-city generation. Clearly massive wind turbines are a non-starter within NYC so that leaves solar. The problem is that a 1 MW solar PV power plant will require between 2.5 acres and 4 acres if all the space needed for accessories are required. Assuming that panels generate five times their capacity a day 43.2 MW of solar panels can generate the 216 MWh of energy available from the East River Energy Storage System and that means a solar array of between 108 and 173 acres. To get the 104,000 MWh needed for the entire NYC peak between 10 and 16 square miles of solar panels will be needed.

Public Policy Concerns

I have previously described how the precautionary principle is driving the CLCPA based on the work of David Zaruk, an EU risk and science communications specialist, and author of the Risk Monger blog. In a recent post, part of a series on the Western leadership’s response to the COVID-19 crisis, he described the current state of policy leadership that is apropos to this discussion:

“The world of governance has evolved in the last two decades, redefining its tools and responsibilities to focus more on administration and being functionary (and less on leadership and being visionary). I have written on how this evolution towards policy-making based on more public engagement, participation and consultation has actually led to a decline in dialogue and empowerment. What is even more disturbing is how this nanny state approach, where our authorities promise a population they will be kept 100% safe in a zero-risk biosphere, has created a docilian population completely unable and unprepared to protect themselves.”

His explanation that managing policy has become more about managing public expectations with consultations and citizen panels driving decisions describes the Advisory Panels to the Climate Action Council. He says now we have “millennial militants preaching purpose from the policy pulpit, listening to a closed group of activists and virtue signaling sustainability ideologues in narrowly restricted consultation channels”. That is exactly what is happening on this panel in particular. Facts and strategic vision were not core competences for the panel members. Instead of what they know, their membership was determined by who they know. The social justice concerns of many, including the most vocal, are more important than affordable and reliable power. The focus on the risks of environmental justice impacts from these power plants while ignoring the ramifications if peaking power is not reliably available when it is needed most does not consider that a blackout will most likely impact environmental justice communities the most.

Conclusion

There are significant implementation issues trying to meet the CLCPA mandates in New York City. Energy storage at the scale needed for any meaningful support to the NYC peak load problem has never been attempted. The in-city generation requirements have to be reconciled with what could actually be available from solar within the City. All indications are that the costs will be enormous. Importantly, I have only described the over-arching issues. I am sure that there are many more details to be

reconciled to make this viable and there are as yet unaddressed feasibility issues.

I have previously shown that the Peak Coalition analysis of peaking plants misses the point of peaking plants and their environmental impacts. The primary air quality health impacts are from ozone and inhalable particulates. Both are secondary pollutants that are not directly emitted by the peaking power plants so do not affect local communities as alleged. While nothing detracts from the need to retire the old, inefficient simple cycle turbines, replacing all the facilities targeted by the Peak Coalition is a mis-placed effort until replacement technologies that can maintain current levels of affordability and reliability are commercially available. At this time that is simply not the case.