The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) became effective on January 1, 2020 and establishes targets for decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing renewable electricity production, and improving energy efficiency. The law mandated the formation of the Climate Action Council to prepare a scoping plan to outline strategies to meet the targets. This is one of a series of posts describing aspects of that process. This post is my reaction to the Power Generation Advisory Panel’s initial strategies.

I am very concerned about the impacts of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) on energy system reliability and affordability. There are very few advocates for the typical citizen of New York who has very little idea about the implications of the CLCPA on energy costs and personal choices. I am a retired electric utility meteorologist with nearly 40-years-experience analyzing the effects of meteorology on electric operations. I believe that gives me a relatively unique background to consider the potential quantitative effects of energy policies based on doing something about climate change. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Power Generation Strategy Comments

I am disappointed by this panel’s strategies. Arguably the strategies from this panel are the most important because a basic tenet of decarbonization is electrification of everything. If the proposed strategies are not realistic then everything else fails. I have no seen no sign that there is sufficient focus on strategies that address reliability and affordability of a completely transformed electric sector.

In a post on the peaking power plant problem in New York City I included a section on public policy concerns. I have previously described how the precautionary principle is driving the CLCPA based on the work of David Zaruk, an EU risk and science communications specialist, and author of the Risk Monger blog. In a recent post, part of a series on the Western leadership’s response to the COVID-19 crisis, he described the current state of policy leadership that is apropos to this panel. He explains that managing policy has become more about managing public expectations with consultations and citizen panels driving decisions than trying to solve problems. He says now we have “millennial militants preaching purpose from the policy pulpit, listening to a closed group of activists and virtue signaling sustainability ideologues in narrowly restricted consultation channels”. That is exactly what is happening on this panel in particular. Facts and strategic vision were not core competences for the panel members. Instead of what they know, their membership was determined by who they know. The social justice concerns of many, including the most vocal, are more important than affordable and reliable power. The emphasis on the risks of environmental justice impacts from the power generation sector is detracting from the need to develop a scoping plan that ensures affordable and reliable electricity.

It is not clear that the members even understand the enormity of the challenge. I used the panel’s email address for public comments last October to suggest a workshop to explain how energy systems work and quantify how much energy is needed and where to provide reliable power to give the panel members a common basis. I even included an overview of the energy system to show why the workshop is needed. There is no sign that anyone on the panel is aware of my comments and there hasn’t been a workshop. I naively believed that that the deep decarbonization workshop would address this need. Unfortunately, the workshop did not provide any discussion of the reliability challenges. Instead, the workshop mostly reinforced the notion that CLCPA targets will be met because of the political will of the State. Long-duration energy storage is the key need and a presentation on that was useful but it did not address the availability or applicability to New York so it is not clear if there is a viable solution to this critical requirement in the timeframe needed. The keynote, hydrogen, and carbon sequestration presentations all sound great superficially but no context relative to New York needs was given and they all have serious technological or implementation issues.

The panel organized itself into four sub-groups: equity, barriers, solutions for the future, and resource mix. They presented ten strategies in the presentation to the Climate Action Council. I address their strategies below.

The equity sub-group presented three strategies. I don’t think these should be stand-alone strategies. Instead, these concerns should be incorporated into strategies for the transition similar to how equity considerations were handled by all the other panels.

The first strategy addressed community Impact suggesting the development of recommendations to identify and proactively address community impacts relating to health concerns, access to renewables and energy efficiency, and siting. Four equity concerns are described:

-

-

-

- Reduce disproportionate impacts in overburdened communities (e.g. the operation of high emission power generation facilities result in significant health concerns for neighboring communities)

- Consider means for increasing access to energy efficiency, solar, and community distributed generation projects to specifically assist disadvantaged communities

- The siting of renewable projects and their potential impact on local communities both in the short and long term, particularly in rural areas

- The impacts on communities (e.g. jobs, revenues, etc.) where energy facilities are being retired

-

-

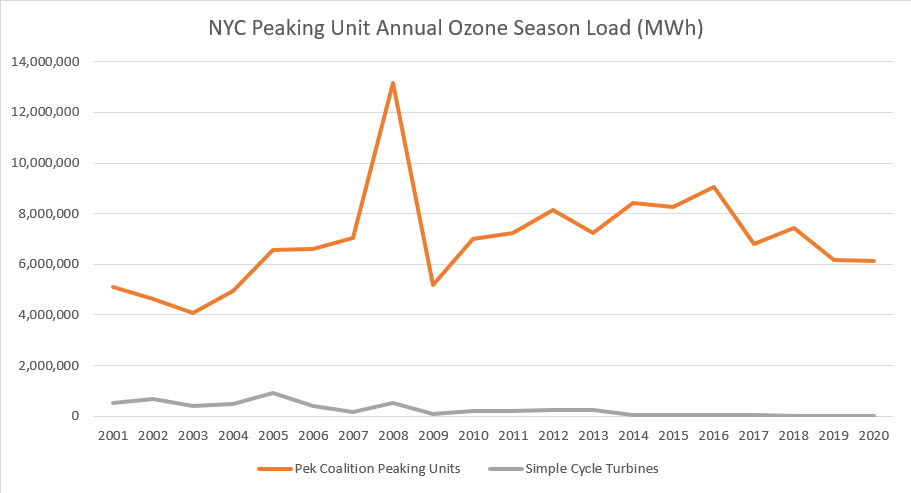

The operation of high emission power generation facilities refers to peaking power plants which has become a rallying topic for environmental justice advocates. Its inclusion confirms my suspicions that panel members need to be provided background information because there are some basic misunderstandings. I prepared and submitted a comment to powergenpanel@dps.ny.gov explaining that the presumption that these peaker plants are contributing to local health impacts because of ozone and particulate matter impacts is simply a wrong premise. I described another problem in another comment that explained that there is a mis-understanding which New York City power plants are for peaking purposes and which ones are used for other services.

Considering means to increase energy efficiency, solar, and community distributed generation projects to specifically assist disadvantaged communities is also problematic. This is a power generation strategy so energy efficiency is a different panel’s concern. In my opinion if this is included then this approach for peaking power should have been a stand-alone strategy. The rationale is to provide equity but in order to do that there are technological challenges that have to be addressed. There are so many challenges that it deserves its own focus but the naïve under-estimation of the challenges emphasized the goal itself over the implementation effort needed. The remaining two equity concerns are non-controversial and could have been easily incorporated into other implementation strategies as necessary.

The second strategy is “Access and Affordability for all (Enabling) –Develop recommendations to ensure New Yorkers have access and can afford to participate meaningfully in NYS’s clean energy future”. Inherent in this strategy is the belief that people want to be able to access clean energy presumably by participating in a community project if they cannot install solar panels at home. Forgotten is the fact that ratepayers have had the opportunity to purchase “green” energy for years but that subscription to those offerings has always been low. Overlooked is the fact that if participating means lower prices for participation in specific programs it also means that everyone not participating in those kinds of programs is footing the bill for everyone who does. As long as there are any people with already unacceptable energy burdens this strategy may do more harm than good.

The final strategy from this subgroup is “Workforce Development (Enabling) –Develop recommendations to enable an equitable clean energy workforce”. Again, this clearly is more appropriate as an equity concern in implementing strategies rather than as a stand-alone strategy.

The Barriers sub-group presented two strategies both of which should get higher priority than suggested by the presentation:

-

-

-

- Clean Energy Siting

- Energy Delivery & Hosting Capacity

-

-

Because the primary decarbonization strategy is electrification, clean energy siting is a primary consideration. This sub-group listed eight issues to explore:

-

-

-

- Optimizing new transmission builds

- Collocated storage with renewable energy projects

- Correctly designing clear and transparent price signals for both energy and interconnection costs

- How to properly track progress and make course corrections as process progresses

- Provide standardized property tax assessments for renewable projects

- Encouraging more robust host community and PILOT plans to increase benefits for community members

- Explore reducing timeframe and restrictions for siting on brownfields and unused industrial land

- Siting projects closer to end user areas

-

-

The first four issues are fundamental implementation issues. Because wind and solar energy is diffuse, transmission has to be developed to get it where it is needed. Because wind and solar energy is intermittent, it is not dispatchable and energy storage is needed to get it when it is needed. New York’s electricity system is de-regulated so the market will dictate whether these resources are developed. The ambitious schedule of the CLCPA targets means that tracking progress is a fundamental requirement to achieve those targets. I agree with them all. The remaining four issues are less important because they address comparatively minor implementation concerns.

Energy delivery and hosting capacity is another primary consideration. The sub-group listed six issues to consider:

-

-

-

- Upgrading aging infrastructure and optimizing the location and operation of new transmission projects, including transmission of off-shore wind, and removing regulatory barriers that make optimization difficult

- Upgrading the transmission system to be able to host more distributed energy resources

- Easing interconnections on both the bulk and distribution levels

- Energy delivery extends beyond transmission to include storage, especially as the saturation of intermittent resources increases

- How should the economic tradeoff between new transmission, energy curtailment, and energy storage be considered

- How to properly track progress and make course corrections as needed

-

-

All of these are fundamental consideration issues. There is one glaring omission however. Wind and solar energy produce asynchronous generation but the transmission grid is synchronous. The need for ancillary services to provide that support must be included.

Solutions for the future addresses the fact that implementation of the CLCPA targets is pushing the limits of technological capabilities. Unfortunately I believe that is contrary to the presumption of many that meeting the goals is only a matter of political will. Two issues were raised:

-

-

-

- Technology and Research Needs

- Market Solutions –Maximize the market participation of different technologies in a way that adds to system efficiency & send correct price signals to resources over time

-

-

The rational for technology and research noted that:

-

-

-

- Adoption of new technology to enable CLCPA goals must be integrated with more traditional investments for continued safe and reliable operation of the grid

- Timeframes for adoption of new technology on the electric grid must be accelerated from the typical timeline of 5+ years from initial commercial product availability to deployment at scale

-

-

Unfortunately, reality as expressed as a potential implementation challenge is that “demonstration and validation of technology frequently requires large scale projects in real world use cases that are both costly and require coordination of many entities.” Clearly there is need for a feasibility study to determine what can be counted on from existing technology and what new technology is needed either for feasibility or affordability. Last year the International Energy Agency (IEA) published “Special Report on Clean Energy Innovation” that concludes that innovation is necessary for jurisdictions to fulfill their de-carbonization targets. The Energy Transition Plan Clean Energy Technology Guide summarizes 400 component technologies and identifies their stage of readiness for the market. It should be used in a feasibility study to rate the potential availability of any technology proposed.

The other issue of market solutions should be a big concern. New York’s electricity system is de-regulated so the market is expected to provide the necessary resources. However, uncertainty is a problematic issue with investors. As a result, new technology may require guarantees for market investors to provide the support that market advocates believe will appear.

The resource mix subgroup presented three strategies:

-

-

-

- Growth of renewable generation and Energy Efficiency

- Effectively Transitioning away from Fossil Fuel Energy Generation

- Deploying Energy Storage and Distributed Energy Resources (DERs)

-

-

The rational for the first strategy sums up the basis for my concerns very well:

“The CLCPA requires 70% renewable electricity by 2030 and 100% carbon free electricity by 2040. We anticipate demand growth of 65% to 80%, dependent on the scale and timing of electrification and whether there are clean alternatives for transportation and buildings, such as bioenergy. The level of electrification needed to achieve GHG reduction goals will increase overall electric load and shift the system peak from summer to winter. There remains a large amount of renewables that must be procured and developed to reach the goals and NYS needs to incorporate flexibility and controllability as we electrify these sectors in order to create a more manageable system.”

As noted before, a feasibility study for the technology is needed. A primary prerequisite is an official estimate of the projected loads when other sectors are electrified. However, I have an even more basic feasibility concern. As a party to the Department of Public Services (DPS) resource adequacy matters proceeding, docket Case 19-E-0530, I have submitted comments (described here and here) based on my background as a meteorologist who has lived in and studied the lake-effect weather region of Central New York. Both E3 and the Analysis Group have done studies of the weather conditions that affect solar and wind resource availability in New York. However, to my knowledge (neither consultant has ever responded to my question on this topic), they have not considered the joint frequency distribution of wind and solar or used solar irradiance data from the NYS Mesonet. In my opinion, both parameters have to be considered together and using airport data or models for cloud cover are inadequate. The Mesonet data set is the only way to have information that adequately represents the local variations in cloud cover caused by the Great Lakes. In order to adequately determine the combined availability of wind and solar I recommend using that data set for the renewable resource availability feasibility study.

The second strategy, “Effectively Transitioning away from Fossil Fuel Energy Generation” could be used as the outline for all the strategies of the panel. The rationale states: “As renewable penetration increases, how do we transition away from fossil fuels while maintaining reliability and safety standards?” The normal convention for priority ranking is to put the most important issues first in the presentation. It is discomforting that this is placed ninth of the ten strategies. It brings up the question just what are the priorities of this panel if reliability and safety concerns are ranked so low?

The final strategy from this workgroup was “Deploying Energy Storage and Distributed Energy Resources (DERs)”. In my opinion, there was insufficient emphasis on technological feasibility in the discussion of energy storage in this strategy. As mentioned earlier, a major shortcoming in these strategies is the lack of any mention of the need for transmission ancillary services. There is recognition that long duration storage will be needed but the fact that the few large battery systems currently deployed are being used for ancillary services and not storage is an obvious barrier that has not been included. Another concern I have with this strategy is that the definition of DER has changed to exclude distributed generation using fossil fuels. Has anyone thought to ask the hospitals with DER systems whether they can put up with the limitations of renewable DERS for their obviously critical need for constant electric power? An ice storm that knocks power off for days will quickly over-tax the capabilities of any renewable and energy storage system to keep a hospital running.

Missing Points

I have mentioned previously that the major missing point in these strategies is that ancillary services are not mentioned. Someone, somewhere has to address the frequency control and reactive power needs of the grid. Obviously, that has to be included in the strategies. It goes beyond simply adding it to a strategy because it is not clear how those services can be incorporated into the market signal to provide them. For example, there are advocates for a carbon price on electricity generation. In this approach any generator that emits CO2 will have to include a carbon price in their bid which serves to provide the non-emitting generators with more revenue. However, solar and wind generators are not paying the full cost to get the power from the generator to consumers when and where it is needed. Because solar and wind are intermittent, as renewables become a larger share of electric production energy storage now provided by traditional generating sources will be needed but there is no carbon price revenue stream for that resource. Because solar and wind are diffuse, transmission resources are needed but solar and wind do not directly provide grid services like traditional electric generating stations. Energy storage systems could provide that support but they are not subsidized by the increased cost to emitting generators. When the carbon pricing proposal simply increases the cost of the energy generated, I think that approach will lead to cost shifting where the total costs of fossil fuel alternatives have to be directly or indirectly subsidized by the public. This result is not in the best interests of low-income ratepayers.

Funding and affordability considerations received short shrift from this panel. In light of the fact that the New York Independent System Operator has proposed a carbon pricing initiative for the electric sector it would seem that a strategy to address that approach or something else should be included. There is another aspect of affordability that should also be addressed. The Department of Environmental Conservation recently released its guidance on the value of carbon. Because the electric sector has documented control costs, this panel should include a strategy to determine if the marginal abatement cost approach should be used for recommendations to the Climate Action Council.

Conclusion

This was the only panel that included specific strategies to address environmental justice concerns. All the other panels incorporated those concerns within their strategies and it would have been appropriate to do the same here. It appears that the idealogues on this panel are more concerned about those concerns than affordability and reliability. In my opinion those should be the primary concerns of this panel because those factors will impact the disadvantaged people of New York the most.

Because of the importance of power generation to the electrification needed to reduce GHG emissions in all sectors, this panel should focus its attention on the challenges of a transition to an electric system that is dependent upon wind and solar resources. I recommend that strategies include a feasibility study of technology needed for the transition, a resource availability study and a cumulative environmental impact analysis. Until this feasibility studies are complete any strategies are simply guessing and the absence of a cumulative environmental impact assessment could mean that the impacts from the cure are worse than impacts from the disease.