On July 18, 2019 New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), which establishes targets for decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing renewable electricity production, and improving energy efficiency. The CLCPA established a council, advisory panels and three working groups. This is a background post on the Climate Justice Working Group which consults with the advisory panels that recommended enabling strategies to the Climate Action Council.

I have written extensively on implementation of the CLCPA because I believe the solutions proposed are not feasible with present technology, will adversely affect affordability and reliability, that wind and solar deployment will have worse impacts on the environment than the purported effects of climate change, and, at the end of the day, meeting the targets cannot measurably affect global warming when implemented. I briefly summarized the schedule and implementation of the CLCPA. I have described the law in general, evaluated its feasibility, estimated costs, described supporting regulations, summarized some of the meetings and complained that its advocates constantly confuse weather and climate in other articles. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

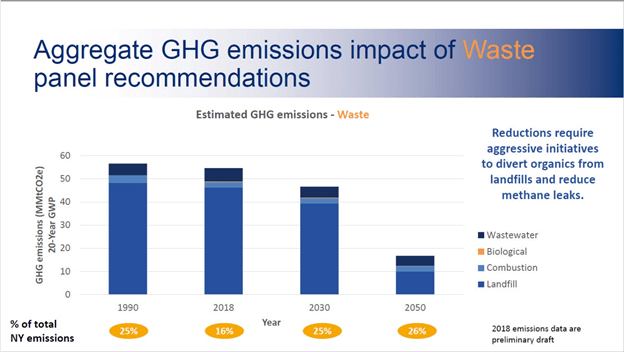

The CLCPA targets are ambitious: relative to a 1990 baseline there is a mandate for a 40% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 and 85% reduction in GHG emissions by 2050 as well as a requirement for 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040. There is no requirement for an assessment of technology and cost feasibility. In order to develop the plans to meet these targets the CLCPA set up ten groups to develop the plan to meet the greenhouse gas emission reduction targets of the law: the Climate Action Council, six advisory panels, and three working groups.

The Climate Action Council (§ 75-0103) consists of 22 members: 12 agency heads, 2 non-agency expert members appointed by the Governor, 6 members appointed by the majority leaders of the Senate and Assembly, and 2 members appointed by the minority members of the Senate and Assembly. Given that 14 members are appointed by the Governor and six more members are appointed by the Democratic majority that passed the legislation there isn’t any pretense for unbiased recommendations.

Climate Action Council Advisory Panels (§ 75-0103, provide recommendations to the council on specific topics, in its preparation of the scoping plan, and interim updates to the scoping plan, and in fulfilling the council’s ongoing duties. The law established advisory panels on transportation, energy intensive and trade-exposed industries, land-use and local government, energy efficiency and housing, power generation, and agriculture and forestry and another panel on waste was added last fall. The panels are also supposed to provide input to the state energy planning board’s adoption of a state energy plan which will incorporate the recommendations of the council. Ostensibly the members of these panels were supposed to be subject matter experts but the reality is that the majority of members did not understand the complexities of the subjects of their panel and were more interested with social justice concerns and their personal advocacy agendas.

Consider, for example, the makeup of the power generation advisory panel. Because electrification of everything is a key implementation strategy, it can be argued that this is the most important panel. The CLCPA states that the “council shall convene advisory panels requiring special expertise”. It is no simple matter understanding how the New York electric system works and I believe that it requires a hard science education or electric sector experience. In my opinion, only five of the fourteen Power Generation panel members have the special expertise necessary. The draft and final enabling initiatives produced by this panel have been described as showing that New York has no idea whatsoever how to “decarbonize” its electric grid.

The Council and the advisory panels were populated mostly by people with overt agendas for greenhouse gas mitigation means that the scoping plan for decarbonizing the NY system will be based more on ideology than reality. Unfortunately, it gets worse because the CLCPA includes three working groups that make not attempts whatsoever to incorporate alternate considerations. The Just Transition, Environmental Justice, and Climate Justice Working Groups were all included in the CLCPA to cater to specific political demographics with only peripheral consideration of the alleged goal to address the “existential” threat of climate change.

The first group, Just Transition Working Group (§ 75-0103), was included to appease organized labor because the closure of fossil-fired power plants will have direct effects on union jobs. This panel is supposed to:

Prepare and publish recommendations to the council on how to address: issues and opportunities related to the energy-intensive and trade-exposed entities; workforce development for trade-exposed entities, disadvantaged communities and underrepresented segments of the population; measures to minimize the carbon leakage risk and minimize anti-competitiveness impacts of any potential carbon policies and energy sector mandates.

They are also charged with preparing a report that includes: the number of jobs created to counter climate change, which shall include but not be limited to the energy sector, building sector, transportation sector, and working lands sector; the projection of the inventory of jobs needed and the skills and training required to meet the demand of jobs to counter climate change; and workforce disruption due to community transitions from a low carbon economy. Note that there is no explicit requirement to determine the number of jobs lost directly due to the CLCPA or indirectly when businesses have to flee the state because of higher energy costs.

This post addresses the other implementation working group, the Climate Justice Working Group (§ 75-0111). The advisory panels are required to “coordinate with the climate justice working group”. The draft scoping plan that outlines how the CLCPA targets will be achieved “shall be developed in consultation with the climate justice working group”. Not surprisingly the final scoping plan has to also be “developed in consultation with the climate justice advisory group”. The group is also responsible for defining “disadvantaged communities” and will meet annually thereafter to review the criteria and affected communities.

The final working group established by the CLCPA is a permanent organization. The Environmental Justice Working Group (§ 75-0101). During the implementation phase each advisory panel is required to coordinate with the environmental justice advisory group and both the draft and final scoping plan are to be developed in “consultation with the environmental justice advisory group”.

The Climate Justice and Environmental Justice working groups have explicit charges. As noted, they are both supposed to coordinate with the advisory panels during the development of the draft and final scoping plans. The Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) may establish an alternative compliance mechanism to be used by sources subject to greenhouse gas emissions limits to achieve net zero emission and are required to “consult with the council, the environmental justice advisory group, and the climate justice working group. In addition, the Climate Justice working group has specific requirements.

The CLCPA has an 85% emission reduction target but it also is “net zero”. The emissions from the remaining 15% are supposed to be offset by §75-0101,10 “Greenhouse gas emission offset projects”. These projects include: “natural carbon sinks including but not limited to afforestation, reforestation, or wetlands restoration; greening infrastructure; restoration and sustainable management of natural and urban forests or working lands, grasslands, coastal wetlands and sub-tidal habitats; efforts to reduce hydrofluorocarbon refrigerant, sulfur hexafluoride, and other ozone depleting substance releases; anaerobic digesters, where energy produced is directed toward localized use; and carbon capture and sequestration; ecosystem restoration” The final type of emission offset projects are those recommended by the council in consultation with the climate justice working group that “provide public health and environmental benefits, and do not create burdens in disadvantaged communities”.

In order to engender support for the Climate Act, legislators included §75-0115, community air monitoring program. This mandate requires DEC to prepare a program demonstrating community air programs in consultation with the climate justice working group. It is currently fashionable for environmental justice advocates to claim that the current air monitoring network established by the Clean Air Act to protect human health is inadequate. The “solution” is to do hyper-local air quality monitoring. I wrote a post on this topic concluding that inadequate monitoring technology and quality control specifications make the results from these systems barely credible.

Nonetheless, the CLCPA includes a second associated mandate that requires DEC, in consultation with the climate justice working group, to develop a strategy to reduce emissions of toxic air contaminants and criteria air pollutants in disadvantaged communities affected by a high cumulative exposure burden. I believe that the basis for this strategy will rely at least in part on the results from the community air monitoring program. One of the primary targets of this campaign against sources in disadvantaged communities are peaking power plants and I have written a series of posts on this topic. As far as I can tell, ozone and inhalable particulate health impacts provide the basis for the claims that these power plants are dis-proportionally affecting environmental justice communities. The fact that both are secondary pollutants that do not directly affect the neighborhoods around these power plants has been ignored to date.

The point should be made that participation on these panels is a burdensome chore. Over the past year, participants have had to endure many meetings and working sessions as well as reviewing information in preparation for the meetings. Many of the participants work for companies that will directly benefit from the transition like renewable energy developers and many more work for non-governmental advocacy organizations whose primary purpose is to foist the clean energy transition on the public in the name of solving the “existential” crisis of climate change. It is not immediately clear why environmental and social justice advocates would be willing to invest their time in this process. Cynic that I am I believe that following the money is a primary motivator.

Section § 75-0117, Investment of funds of the CLCPA mandates that:

State agencies, authorities and entities, in consultation with the environmental justice working group and the climate action council, shall, to the extent practicable, invest or direct available and relevant programmatic resources in a manner designed to achieve a goal for disadvantaged communities to receive forty percent of overall benefits of spending on clean energy and energy efficiency programs, projects or investments in the areas of housing, workforce development, pollution reduction, low income energy assistance, energy, transportation and economic development, provided however, that disadvantaged communities shall receive no less than thirty-five percent of the overall benefits of spending on clean energy and energy efficiency programs, projects or investments and provided further that this section shall not alter funds already contracted or committed as of the effective date of this section.

The point has often been made that the 40% goal is the floor and that more is appropriate. Of course, the primary discussion is just what programs should be funded and the Climate Justice Working Group is positioning itself to be the final arbiter of those decisions.

Unfortunately, the reality is that the CLCPA is supposed to be a greenhouse gas mitigation program and that funding of any project that does not directly lead to emissions reductions dilutes the cost-effectiveness of the investments. For example, the investments made with the proceeds of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative have only been responsible for 5% of the observed reductions at a $858 per ton reduced rate because monies have been diverted like this mandate and because clean energy and efficiency programs are not very cost effective. Coupled with the facts that mitigation efforts are going to be expensive and the CLCPA does not incorporate a funding mechanism, this mandate will make reaching the targets even more difficult.

Climate Justice Working Group

This section describes the specific mandates of the Climate Justice Working Group (§ 75-0111).

The climate justice working group has been created within DEC. There are representatives from: environmental justice communities, DEC, the Department of Health, the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority, and the Department of Labor.

Environmental justice community representatives shall be members of communities of color, low-income communities, and communities bearing disproportionate pollution and climate change burdens, or shall be representatives of community-based organizations with experience and a history of advocacy on environmental justice issues, and shall include at least three representatives from New York city communities, three representatives from rural communities, and three representatives from

upstate urban communities.

I think the biggest responsibility of the working group is to develop the criteria that define disadvantaged communities. The working group is supposed to work with DEC and the departments of health and labor, the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority, and the environmental justice advisory group to “establish criteria to identify disadvantaged communities for the purposes of co-pollutant reductions, greenhouse gas emissions reductions, regulatory impact statements, and the allocation of investments”.

The CLCPA establishes guidelines for the disadvantaged communities criteria. In general, there are supposed to be identified based on geographic, public health, environmental hazard, and socioeconomic criteria. Of course, the devil is in the details but those criteria “shall include but are not limited” to:

- Areas burdened by cumulative environmental pollution and other hazards that can lead to negative public health effects;

- Areas with concentrations of people that are of low income, high unemployment, high rent burden, low levels of home ownership, low levels of educational attainment, or members of groups that have historically experienced discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity; and

- Areas vulnerable to the impacts of climate change such as flooding, storm surges, and urban heat island effects.

Once the draft guidelines are prepared there are requirements for hearings, a public comment period and “meaningful opportunities for public comment for all segments of the population that will be impacted by the criteria, including persons living in areas that may be identified as disadvantaged communities under the proposed criteria”. Once the criteria have been established the group will meet no less than annually to review the criteria and methods used to identify disadvantaged communities. They “may modify such methods to incorporate new data and scientific findings”. Finally the climate justice working group shall annually “review identities of disadvantaged communities and modify such identities as needed”.

Membership

I researched the background of the nine at large members and four members from state agencies and summarized that information here. There is a significant spread of the quality of the at large members. Several are nationally recognized experts on environmental justice issues. Others have extensive experience advocating for environmental justice. Those people all are working at well known organizations. On the other hand, a few have little environmental justice background and seem to have been chosen to fulfill the geographical requirements.

With regards to the geographical requirements for three each representing New York City, Upstate Urban and Rural communities I don’t think rural disadvantaged communities are represented well. In the first place two represent the Adirondacks. That area is a special case with unique constraints for communities within the Adirondack State Park. No one comes from the communities in Appalachia and I think the needs and interests of those disadvantaged communities should have been represented.

There is another important point. While the background of many of the members is well suited for the charge to advise the Climate Action Council with respect to climate justice issues for disadvantaged communities, I did not see any member with appropriate technical education or experience to critique the technical enabling strategies of the advisory panels with one exception. There are some members with planning experience that could provide meaningful comments to the land use and local government advisory panel. As a result. I don’t think that technical criticisms from this working group on the advisory panel enabling strategy recommendations should carry much weight.

Conclusion

Similar to all the other panels and working groups, the membership of the Climate Justice Working Group is a mixed bag. Some are clearly experts in their fields. However, that does not necessarily mean that their opinions on all topics are meaningful. Moreover, given that advocacy appears to have been a primary criterion for membership the passion for their “cause” should be considered in the context of society as a whole.

At the time of this writing there isn’t much to draw any conclusions on the value of their recommendations. They have commented on a couple of advisory panel enabling strategies which I will discuss in an upcoming post but they have not proposed criteria for the definition of disadvantaged communities. Because at least 35 to 40% of the CLCPA project funding will be targeted to those communities that definition is important. Cynically, I believe that designs on that funding is a prime driver of the rationale to become a member.