The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a carbon dioxide control program in the Northeastern United States. One aspect of the program is a program review that is a “comprehensive, periodic review of their CO2 budget trading programs, to consider successes, impacts, and design elements”. This post describes my comments at the start of the third program review public participation process.

I have been involved in the RGGI program process since its inception. I blog about the details of the RGGI program because very few seem to want to provide any criticisms of the program. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

RGGI is a market-based program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It is a cooperative effort among the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia to cap and reduce CO2 emissions from the power sector. According to a RGGI website:

“The RGGI states issue CO2 allowances which are distributed almost entirely through regional auctions, resulting in proceeds for reinvestment in strategic energy and consumer programs. Programs funded with RGGI investments have spanned a wide range of consumers, providing benefits and improvements to private homes, local businesses, multi-family housing, industrial facilities, community buildings, retail customers, and more.”

Proponents tout RGGI as a successful program because participating states have “cut carbon pollution from their power plants by more than half, improved public health by cutting dangerous air pollutants like soot and smog, invested more than $3 billion into their energy economies, and created tens of thousands of new job-years”. Others have pointed out that RGGI was not the driving factor for the observed emission reductions. My work supports that conclusion and points out that the cost-effectiveness of the investments from this carbon tax reduce CO2 emissions at a cost of $858 per ton which is far greater than the social cost of carbon metric. In other words, this is not a cost-effective way to reduce CO2 emissions.

Third Program Review

According to the program review link on the RGGI website:

The RGGI states completed the First Program Review in February 2013 and completed the Second Program Review in December 2017, resulting in the 2017 Model Rule. Now the states have initiated the Third Program Review to consider further updates to their programs.

On February 2, 2021, the RGGI states released a statement announcing the plan for the Third Program Review, and in Summer 2021 the states released a preliminary timeline for conducting the Third Program Review. Note that this timeline is subject to change and may be revised over time.

To support the Third Program Review, the states will:

-

-

- Conduct technical analyses, including electricity sector modeling, to inform decision-making related to core Program Review topics, such as the regional CO2emission cap.

- Solicit input from communities, affected groups, and the general public on the Program Review process and timeline, core topics and objectives, modeling assumptions and results, and other policy and design considerations.

- Convene independent learning sessions with experts and other interested parties on key design elements.

-

Public participation is a key component of a successful Program Review. The RGGI states will conduct public engagement throughout Program Review, including periodic public meetings and accompanying open comment periods, to share updates and solicit public feedback.

RGGI has released a list of issues to be considered in its Topics for Public Discussion. The RGGI states are seeking comments on the future size and reduction trajectory of the allowance caps and the allowance bank. Comporting with the current fad they are also considering environmental justice and equity considerations. The RGGI program includes auction mechanisms and they have asked for comments on them. They also asked for comments on the compliance mechanism and the offset program.

In brief, my comments recommend making no changes. In the next few years, the RGGI allowance market will change to the unprecedented emissions trading situation in which the majority of the RGGI allowances are held by entities who purchased allowances for investment rather than compliance purposes. No one knows how the market will react and the compliance mechanisms are working well as is so there is no need to change anything at this time. The purpose of this post is to describe why I believe changes to the allowance cap and reduction trajectory are unnecessary.

I have prepared a simple analysis that projects the margin between allowances available and emissions (Table 1) for a first cut estimate of the RGGI allowance market and compliance requirements. I downloaded CO2 mass, heat input, and primary fuel use data from the EPA Clean Air Markets Division database from 2009 to 2020 for Acid Rain Program units rather than RGGI program units so that I could include data from New Jersey and Virginia.

While Table 1 lists totals for five categories of fuel use: natural gas, coal, residual oil, diesel oil, and other fuels, it is instructive to look at a breakdown of the fuels over time. Table 2 lists the CO2 mass, heat input and calculated CO2 rate (lbs/hr) by fuel category for the combined nine states that have been in RGGI since 2009, New Jersey and Virginia. The final row lists the percentage change between the first three years of RGGI and the latest three years. In nine-state RGGI CO2 mass is down 39%, heat input is down 28% and the CO2 rate is down 16%. However, the fact that the CO2 rates for New Jersey and Virginia are down more than the RGGI states indicates that the economics of fuel switching to natural gas is the primary reason that CO2 emissions have decreased as observed in the RGGI region.

Table 1 lists the allowance cap and adjusted cap from 2009 to 2030 in the first three data columns. The observed CO2 mass and heat input totals for the five fuel categories are in the last columns. Starting in 2021, the estimated total allowances available expected at the end of each year are listed. The 2021 value is based on the latest Potomac Economics report on the secondary market report. From a compliance standpoint the key parameter is the margin between the allowances available and the emissions. For each year subsequent to 2021 the allowances available equals the previous year allowances minus that year’s emissions plus the allowances from the adjusted cap through 2025 and unadjusted cap through 2030.

Based on the observation that fuel switching is the primary CO2 reduction methodology to date, the emission projection in the table forces coal, residual oil and diesel oil to go to zero by 2030. The projected emissions are summed and the margin (difference between allowances available and emissions) is calculated. Using these assumptions, the allowance bank and the margin continue to decrease suggesting that there will be no major upheavals in compliance strategies or allowance prices. Of course, projecting future emissions is fraught with difficulties and uncertainties but this approach is probably conservative and actual reductions will likely be greater.

It is also appropriate to review the emission reduction results of RGGI relative the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) cost-effectiveness parameter. I believe that the only reductions from RGGI that can be traced to the program are the reductions that result from direct investments of the RGGI auction proceeds. Information necessary to evaluate the performance of the RGGI investments is provided in the RGGI annual Investments of Proceeds updates. In order to determine reduction efficiency, I had to sum the values in the previous reports because the reports only report lifetime benefits. In order to account for future emission reductions against historical levels and to compare values with the SCC parameter, the annual reduction parameter must be used. Table 3, Accumulated Annual RGGI Benefits, lists the sum of the annual avoided CO2 emissions generated by the RGGI investments from previous reports. The total of the annual reductions is 2,259,203 tons while the difference between the baseline of 2006 to 2008 compared to 2019 emissions is 72,908,206 tons. Therefore, the RGGI investments are only directly responsible for less than 5% of the total observed reductions since RGGI began in 2009. Also note that the cumulative annual RGGI investments are $2,795,539,789 and that means that the cost per ton reduced is $857.74.

Based on comments in previous program reviews there will undoubtedly be calls to make the allowance cap “binding” that is to say force emission reductions to meet a particular emission reduction trajectory. While the projections above do not reduce emissions as much as the arbitrary 3% reduction target from the previous program review, there are potential consequences if a more stringent reduction is mandated.

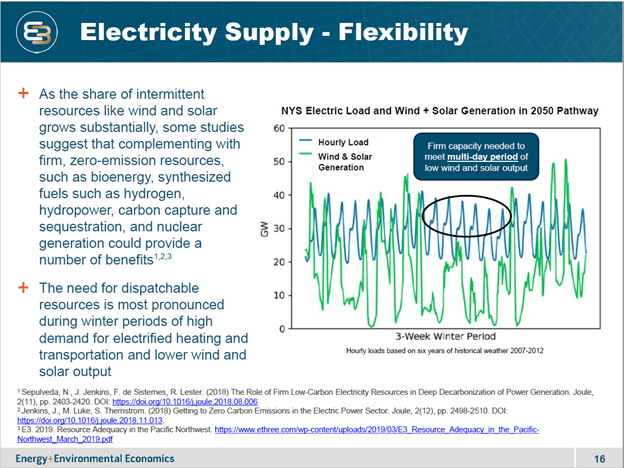

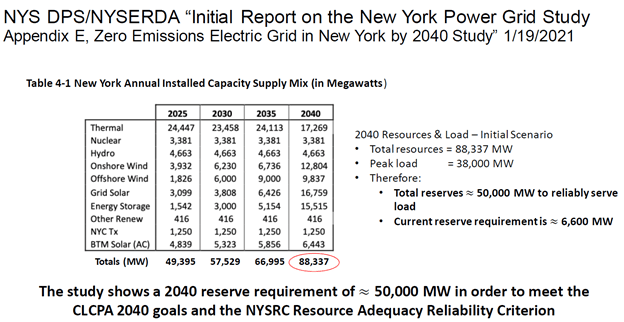

The most important consideration to keep in mind is that CO2 control is different than sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and particulate matter because there are no cost-effective controls available for existing facilities. As the data show, fuel switching is the primary reason for the observed emission reductions but once the facility has changed to a lower emitting fuel the only options at a power plant is to become more efficient and burn less fuel or stop operating all together. Fuel costs are a major factor affecting the price of generation so keeping that price as low as possible to improve competitiveness has always been a priority objective. Consequently, it is unlikely that this could be a source of many future reductions. If it ever comes to the point that allowances are unavailable to operate that could threaten reliability, so it is imperative that RGGI never tighten the cap so low that affected sources are unable to operate due to unavailable allowances.

Theory suggests that as the market gets tighter that the allowance price will rise. If the allowance price exceeds the Cost Containment Reserve trigger price, then allowances equal to 10% of the cap will be released to the market. Because that is greater than the 3% reduction target, that suggests that discouraging a tight market supports greater emission reductions.

Conclusion

As the RGGI states embark on another program review process I hope that they will consider the actual results of the program to date. RGGI has demonstrated that a cap-and-auction emissions trading program can be set up and work well. However, the fact is that any emissions trading approach for CO2 has to acknowledge that there are limited options for cost-effective reductions. I believe that political considerations have diluted the effectiveness of RGGI investments for emission reductions so that the investments are not cost effective relative to the social cost of carbon value of reductions.

I believe that the goal of RGGI should be to balance the allowance cap with observed emissions so that the allowance bank is only used for year-to-year variations in weather-related excess emissions. Over time as RGGI investments fund zero-emission energy sources it may become necessary to adjust the emission reduction trajectory but that should be based on observations and not model projections. If this recommended approach is chosen then the RGGI program can continue to operate without threatening reliability and continue to produce revenues for the RGGI states.