Note: When this was written and posted the recording was not available. The Session recording was posted on August 30, 2021

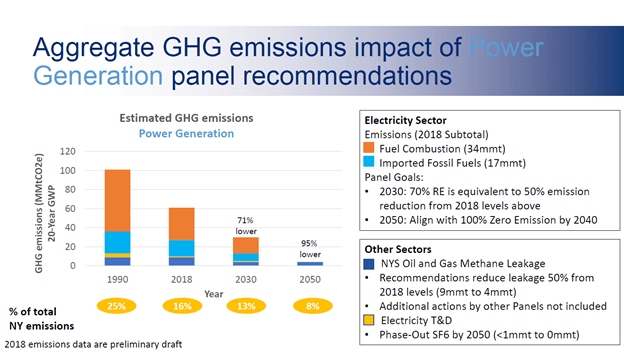

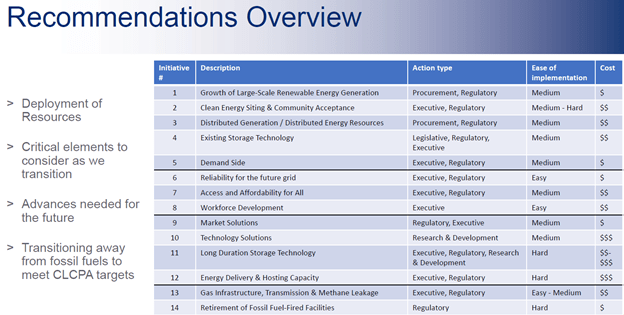

On July 18, 2019 New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), which establishes targets for decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing renewable electricity production, and improving energy efficiency. Over the last year Advisory Panels to the Climate Action Council have developed and submitted recommendations for consideration in the Scoping Plan to achieve greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions economy-wide. This is one in a series of articles about this process.

On August 2, 2021, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) held a Reliability Planning Speaker Session to describe New York’s reliability issues to the advisory panels and Climate Action Council. All the speakers but one made the point that today’s renewable energy technology will not be adequate to mantain current reliability standards and that a “yet to be developed technology” will be needed. This post addresses the study that was the basis for the claim by Vote Solar that “integrating renewables into the grid while maintaining reliability is possible, and in fact cost effective” is fatally flawed.

I have written extensively on implementation of the CLCPA because I believe the solutions proposed will adversely affect reliability and affordability, will have worse impacts on the environment than the purported effects of climate change, and cannot measurably affect global warming when implemented. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

This post is a follow up to an earlier description of the presentations made at the NYSERDA Reliability Planning Speaker Session on August 2, 2021. The first article was a detailed description of the following presentations:

- New York State Reliability Council (NYSRC) – Mayer Sasson, Steve Whitley, & Roger Clayton

- New York Independent System Operator (NYISO) – Zach Smith

- Utility Consultation Group – Margaret Janzen (National Grid) and Ryan Hawthorne (Central Hudson)

- New York State Department of Public Service (DPS) – Tammy Mitchell

- Vote Solar – Stephan Roundtree

- New York Department of State Utility Intervention Unit – Erin Hogan

The article included background information on the organizations as well as highlights from each presentation. I also prepared a condensed version that was edited down even further and published at Natural Gas Now.

The advisory panels who are charged with providing recommendations to the Climate Action Council and the Council itself have been working on implementation plans for the last year. During the development of the advisory panel recommendations, it was obvious that reliability was only receiving token consideration and that many of the panel and council members did not understand the issues and requirements for a reliable energy system. As a result of many comments, this briefing on the topic of electric system reliability was set up.

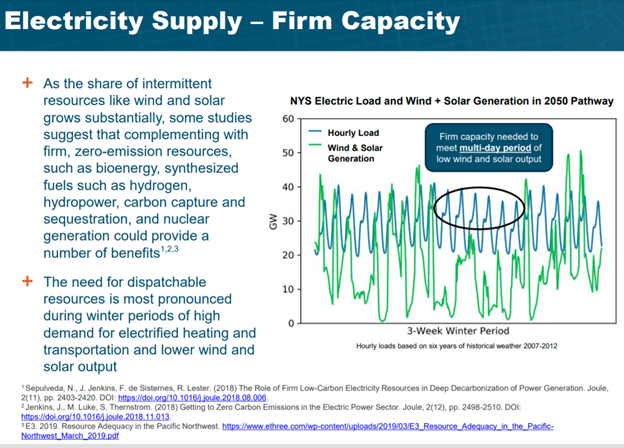

In my previous articles I concluded that there was a common warning admonition in most of the presentations: today’s renewable energy technology is insufficient to develop a reliable electric system with net-zero emissions. The NYSRC notes that “substantial clean energy and dispatchable resources, some with yet to be developed technology, over and above the capacity of all existing fossil resources that will be replaced” needs to be developed. The NYISO explicitly points out that a “large quantity of installed dispatchable energy resources is needed in a small number of hours” that “must be able to come on line quickly, and be flexible enough to meet rapid, steep ramping needs” but only implicitly points out that these are magical resources that do not exist yet for utility-scale needs. The utility consultation group explains that “technology development and diversity of clean resources are essential for long term success” but provide no details of the enormity of that task. Even the DPS makes the point that “evaluating and implementing advanced technologies to enhance the capability of the existing and future transmission and distribution system” is necessary for future reliability. The Utility Intervention Unit does not provide a comparable warning but does stress the importance of planning and the need to address new technologies. Obviously relying on as yet unproven technology to transition the electric system on the schedule of the CLCPA is a serious threat to reliability.

There was one exception to this message. Vote Solar claimed that “integrating renewables into the grid while maintaining reliability is possible, and in fact cost effective”. In my previous articles I blamed the speaker’s inexperience and lack of background on this flawed argument. Since then, and thanks to an unnamed colleague, I have found the likely source of his mis-information as described below.

Local Solar Roadmap

Late last year the report, “Why Local Solar for All Costs Less,” described the results of a new distributed energy resources (DER) planning model. According to a trade press story: the “planning model that includes what most integrated resource plans and solar cost-benefit analyses still leave out — a detailed and long-term view of the distribution system”. “Developed by industry consultants Vibrant Clean Energy (VCE), the model provides a Local Solar Roadmap rooted in a super-granular and highly mathematical view of grid planning. Power flows and resources on the distribution system are looked at in slices of 5 minutes and 3 square kilometers. The operational variables built into the model are equally detailed, encompassing multiple applications for energy storage, emerging technologies such as hydrogen, and increasing stress on the system due to climate change.” Given that Vote Solar was one of the sponsoring organizations and the use of common graphics and tables I am sure that this is the basis for the alternative view presented by Vote Solar.

The results are summarized in a slide presentation and there is an overview summary report that provide a general overview of the approach and results. The executive summary in the report explains that:

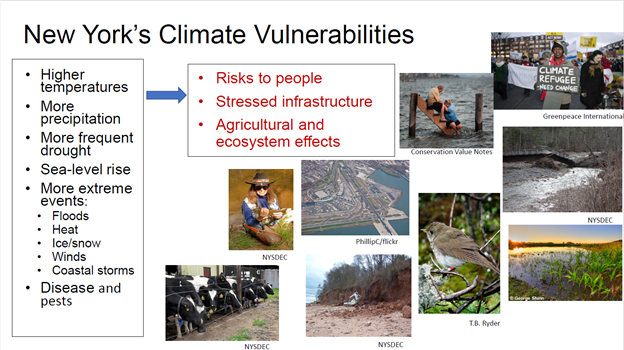

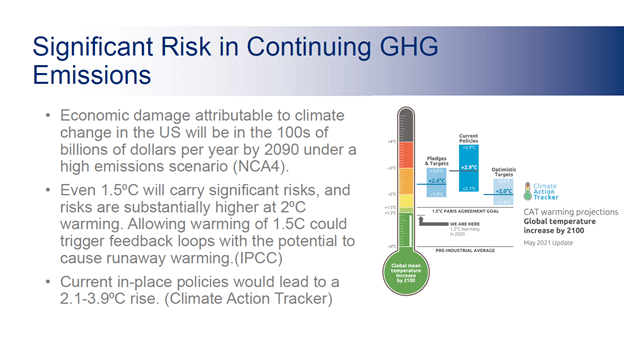

The electricity system in the United States (US) is considered to be one of the largest machines ever created. With the advent of clean and renewable technologies, a widespread evolution is occurring. The renewable technologies are lower cost than fossil thermal generation on a levelized cost basis, but their variability creates new and unique constraints and opportunities for the electricity system of the next several decades. Superimposed on the changing structure of the electricity system is a damaged climate that will continue to worsen as mankind continues to emit greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution into the atmosphere.

The first problem with the report shows up in the first paragraph of the executive summary: “renewable technologies are lower cost than fossil thermal generation on a levelized cost basis”. Levelized cost is defined as “a measure of the cost of an energy generation system over the course of its lifetime, which is calculated as the per-unit price at which energy must be generated from a specific energy source in order to break even. The levelized cost of an energy generation system (LCOE) reflects capital and operating and maintenance costs, and it serves as a useful measure for comparing the cost of, say, a solar photovoltaic plant and a natural gas-fired plant.” The problem is that comparing costs using this measure only incorporates the costs of the facility itself not the cost to provide reliable power when and where it is needed. Storage, load balancing and grid integration needs to be developed and those costs are necessary to cover for the intermittent and diffuse nature of wind and solar. Not acknowledging those costs is a common trick of renewable energy advocates when claiming lower costs.

This analysis “proves” that not only are renewable energy sources the best approach but also goes on to claim that it is not necessary to rely on utility-scale wind and solar facilities. Their work supposedly proves that large additions of distributed energy resources (DER) are the best approach for the future. They describe conventional thinking as follows:

The new, smarter approach is described as follows:

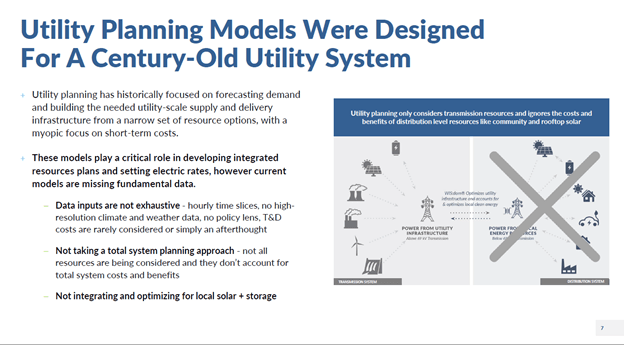

Obviously, renewables are emphasized but their grid of the future has at least ten times more local solar and storage. The basis of the claim is new and better models. The summary slide presentation goes on to argue that the new model is needed to because “utility planning models were designed for a century old utility system”.

The authors claim that “These models play a critical role in developing integrated resources plans and setting electric rates, however current models are missing fundamental data” and that one of the missing pieces is “high resolution climate and weather data”. It is not clear to me whether they don’t know or choose to ignore that current utility planning relies on multiple models. The reliability presentations described models used to explicitly address reliability issues that incorporate historical weather data. In the past it was not necessary to consider short-term (less than one hour) weather variations because the generating facilities did not fluctuate as much as wind and solar. However, the work that NYSRC and NYISO are doing now does consider those fluctuations and uses shorted term data.

The complaint that transmission and distribution costs are “rarely considered or simply an afterthought” may be true elsewhere but New York’s current reliability planning process does consider them. I also consider the claim that “they don’t account for total system costs and benefits” disingenuous for anyone that invokes the levelized cost basis to “prove” that wind and solar are cheaper than traditional generating facilities. The point of all these arguments is that a new and better model is needed.

WIS:dom®-P

The overview summary report describes the new model that “proves” their claims:

The present study demonstrates, quantifies and evaluates the potential value that distributed energy resources (DERs) could provide to the electricity system, while considering as many facets of their inclusion into a sophisticated grid modeling tool. The Weather-Informed energy Systems: for design, operations and markets planning (WIS:dom®-P) optimization software tool is utilized for the present study. A detailed technical document of the WIS:dom®-P software can be found online. The modeling software is a combined capacity expansion and production cost model that allows for simultaneous 3-kilometer, 5-minute dispatch and power flow along with multi-decade resource selection. It includes detailed representations of fossil generation, variable resources, storage, transmission and DERs. It also contains policies, mandates, and localized data, as well as engineering parameters and constraints of the electricity system and its components. Some novel features include highly granular weather inputs over the whole US, climate change-induced changes to energy infrastructure, land use and siting constraints, dynamic transmission line ratings, electrification and novel fuel production endogenously, and detailed storage dispatch algorithms.

WIS:dom®-P is described as a “state of the art, fully combined capacity expansion and production cost model , developed to process vast volumes of data”. It simultaneously “co-optimizes for: “(1) Capacity expansion requirements (generation, storage, transmission, and demand side resources); and (2) Dispatch requirements (production costs, power flow, reserves, ramping and reliability)”.

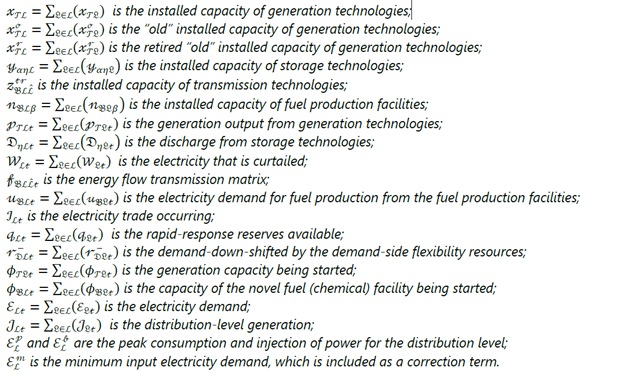

The model documentation is a great example of intimidation by equation and jargon. In order to run the model, the user defines 25 parameters ranging from “amortized capital and fixed costs for generation technologies” to “the fuel cost per unit of primary energy for generation technologies”. Each parameter covers a range of options that vary by location. Considering the fact that the model can cover the contiguous United States parameter definition is a daunting task. The model optimizes a further 21 internal variables. These are not variables in the elementary sense representing a single value. Instead, they are multi-dimensional representations of the, for example, “installed capacity of generation technologies” and “electricity demand” covering an area up to the size of the continuous United States. Each of the 46 parameters gets its own symbol as exemplified by the internal variable list below:

The mathematical formulation of the objective function is:

Don’t worry I am not going to dissect the formulation. I just want to make the point that the authors of the program are very likely on a different level of mathematical understanding than the sponsors of the solar advocacy groups who wanted this analysis. Frankly they are on a different level than me, an old retired guy who might have been able to dissect this 50 years ago but who has long since forgotten much of the mathematics behind this optimization methodology. However, I understand enough to question whether this approach adequately addresses the issues that the NYSRC, NYISO and DPS have analyzed in their work.

Ultimate Problem

The question for the reader is why the WIS:dom®-P approach provides a different answer than the other organizations that presented at the reliability speaker session. I believe that the reason is that all the others are addressing resource planning for the worst-case situation when load peaks. In the past, reliability planning focused on the resources needed for peak summer loads when energy use increases above normal load to provide extra load for air conditioning. The New York energy planners all recognize that when the CLCPA requires electrification of heating and transportation that the peak load will shift to the winter. This leads to the bigger problem that the availability of solar and wind resources during the winter peak also has to be considered when it is expected to be much lower than in the summer. I agree with the conclusion that the future worst-case will be a multi-day wind lull in the winter when solar energy availability is low and wind is also low but I am uncomfortable that analyses done to date adequately consider renewable resource availability during those periods.

I was unable to conclusively determine how worst-case meteorological conditions were addressed in the WIS:dom®-P approach. The documentation states “The model was initialized and aligned with historical data from 2018 and then the simulations evolved the electricity system across the contiguous United States (CONUS) from 2020 through 2050 in 5-year investment periods”. Elsewhere it states “Typically, seven calendar years are also simulated after a pathway solution is found. Future simulations will also include 175 years of 50-km, hourly data to determine the robustness of solutions”. It also notes that the supply and demand balance equation set includes: “the weather-driven (wind, solar, and hydro) resource potential, charge/discharge cycles of storage and demand flexibility, and changes in demand requirements throughout the entire simulation period” among other things that suggests that the model incorporates meteorological effects on resources. The formulation of the reserve margin (eq. 1.14.3) suggests that the calculations are on an annual basis:

The advantage of Eq. (1.14.3) is that it incorporates numerous years of weather data in a reduced form that is mathematically tractable. Some disadvantages persist. First, the minimum years (time step by time step) can jump around across the dataset. Secondly, the weather and demand are decoupled from each other. Finally, to understand the dynamics of conventional generation, storage and DSM, the original weather year time step data are used, which could underestimate their performance. Overall, however, it does provide a robust evaluation of the VRE contribution to planning reserve margins over a wide range of possible conditions.

This leads me to believe that the fatal flaw in the WIS:dom®-P approach is that the optimization occurs on an annual basis. In order to ensure that adequate electricity is available when needed the most during the winter wind lull, the optimization balancing has to address the specific requirements of that period. Unless the renewable resource availability constraints are addressed for the energy storage estimates during the worst-case period, the true magnitude of the resources needed to keep lights on during those conditions remains unknown. Everyone else recognized this constraint and consequently raised a common concern about current renewable technology.

Conclusion

In the previous posts I wondered if the Climate Action Council will address the issues raised by the professionals or cater to the naïve dreams of the politically chosen members of the Power Generation Advisory Panel. This analysis shows that the basis for their dreams of a “smarter” planning solution are dangerous because the supporting analysis does not address the worst case. If electric planning does not address those worst-case conditions, then the inevitable result will be a Texas style blackout that will have enormous costs and result in people freezing to death. The severe winter weather in Texas caused at least 151 deaths, property damage of $18 billion, economic damages of $86 billion to $129 billion, and $50 billion for electricity over normal prices during the storm. This is comparable to the costs of superstorm Sandy. However, the costs for one are preventable but the costs for a storm like Sandy are not.