Two proceedings are dancing around the issue of affordability associated with the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act or CLCPA) emission reduction mandates. The New York State Department of Public Service First Annual Informational Report on Overall Implementation of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act includes cost estimates for existing programs. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) are implementing the New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) proposed by Governor Hochul which is a market-based program to raise revenues for the strategies necessary to meet the mandates. This post compares the costs associated with programs considered in the two proceedings.

I have been following the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 300 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. I have devoted a lot of time to the Climate Act because I believe the ambitions for a zero-emissions economy embodied in the Climate Act outstrip available renewable technology such that the net-zero transition will do more harm than good. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Climate Act Background

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050 and an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% reduction by 2030. The Climate Action Council is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlines how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” In brief, that plan is to electrify everything possible and power the electric grid with zero-emissions generating resources. The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to write a Draft Scoping Plan. After a year-long review the Scoping Plan recommendations were finalized at the end of 2022. In 2023 the Scoping Plan recommendations are supposed to be implemented through regulation and legislation.

Cap-and-Invest Background

According to the Cap-and-Invest Analysis Inputs and Methods webinar (Inputs and Methods Webinar Presentation and View Session Recording) on June 20, 2023, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSE$RDA) are developing the New York State Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) Program to meet the greenhouse gas emission limits and equity requirements of the Climate Act.

The NYCI feedback webinars all included the following slide that describes the program. Setting a cap is supposed to provide compliance certainty and the revenues generated “will minimize potential consumer costs while supporting critical investments” in the control strategies necessary to meet the Climate Act targets.

NYCI Policy Modeling

The Analysis Inputs and Methods webinar mentioned above described the modeling analyses planned to support the development of the program: “This analytics study will assess potential market outcomes and impact from the proposed New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) program.”

In order to evaluate the effects of different policy options, the Hochul Administration has proposed policy modeling. This kind of modeling analysis forecasts future conditions for a baseline or “business-as-usual” case, makes projections for different policy options, and then the results are compared relative to the business-as-usual case. I disagree with the presumptions in the proposed modeling associated with which programs should be included.

The Scoping Plan modeling used a reference case that included “already implemented” programs and the NYCI Cap-and-Invest Analysis Inputs and Methods webinar proposed to use the same framework. Starting with the reference case developed for the Scoping Plan, the NYCI modeling proposed to add policies enacted since then. This reference case approach is misleading because it under estimates the total cost to meet the Climate Act emission reduction mandates.

I maintain that it is more appropriate to compare the policy cases to a base case that excludes all programs intended to reduce GHG emissions. NYCI revenues are supposed to “minimize potential consumer costs while supporting critical investments”. I believe that statement argues that NYCI proceeds are intended to fund all the control programs necessary to meet the Climate Act mandates and not exclude programs that were already implemented.

PSC Informational Report

On July 20, 2023 the first annual informational report (“Informational Report”) on the implementation of the Climate Act was released. According to the press release:

The Climate Act’s directives require the Commission to build upon its existing efforts to combat climate change through the deployment of clean energy resources and energy storage technologies, energy efficiency and building electrification measures, and electric vehicle charging infrastructure. In recognition of the scale of change and significant work that will be necessary to meet the Climate Act’s aggressive targets, the Commission directed DPS staff to assess the progress made in line with its directives under the Climate Act and to provide guidance, as appropriate, on how to timely meet the requirements of the Climate Act.

The Department of Public Service presentation on the Informational Report notes in the following conclusion slide that “ the estimates of total funding authorized by the Commission to date for various clean energy programs in some instances reflect actions that pre-date the enactment of the Climate Act.” This is the only reference to “already implemented” programs. The conclusion states that the information presented “represents direct effects of CLCPA implementation only, and only the portion of direct effects of programs over which the Commission has oversight authority.” I interpret that to mean that they are not concerned with which program implements the necessary control strategies but only the results of all the programs relative to the Climate Act mandates.

The Informational Report also notes that “It is difficult to pull out exactly what costs we would have otherwise incurred for infrastructure investment vs. the cost of CLCPA.” This is the reason a base case is necessary. You need some estimate of investments that would have occurred were it not for the policy. In my opinion if they were worried about the difference between pre-CLPA investment costs vs. CLCPA-mandated investments they would have mentioned it here. Because the Investment Report does not distinguish between costs for programs that pre-date the Climate Act and programs that are mandated by the Climate Act itself, I conclude that the NYCI modeling analyses should follow that precedent and not include “already implemented” control strategy programs.

Implementation Report Costs

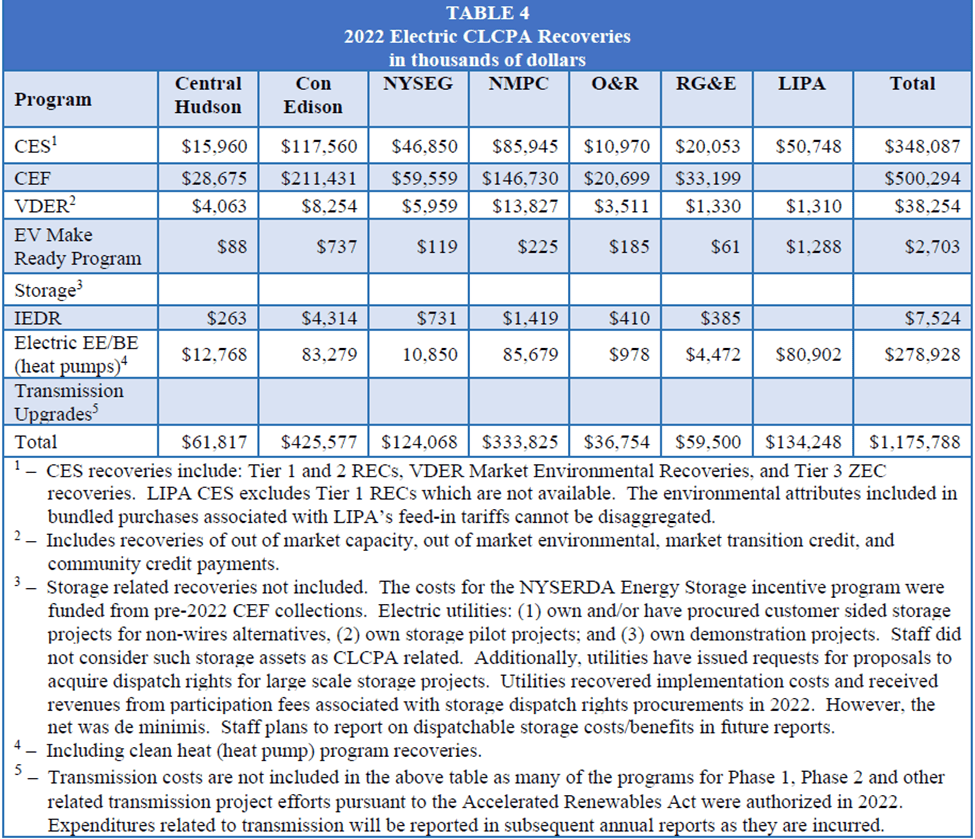

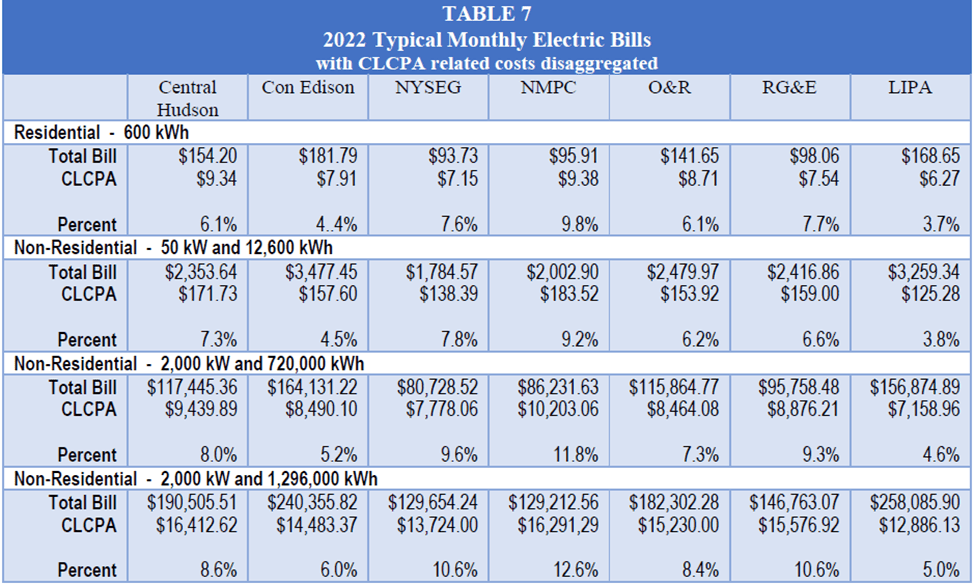

I converted the tables in the Implementation Report to a spreadsheet so that I could combine the data from multiple tables. Three tables are of particular interest: Table 4: 2022 Electric CLCPA Recoveries, Table 7: 2022 Typical Monthly Electric Bills with CLCPA related costs disaggregated, and Table 8: Authorized Funding to Date.

Table 4: 2022 Electric CLCPA Recoveries summarizes costs recovered in 2022 by utilities for electric programs. The costs recoveries include: CES (electric only), CEF (electric only), certain VDER (electric only), Electric Vehicle Make Ready Program (electric only), Clean Heat programs (electric only), Integrated Energy Data Resource (electric only), and Utility Energy Efficiency programs (electric and gas). The table states that $1,175,788,000 in Climate Act costs were recovered in 2022.

Table 7: 2022 Typical Monthly Electric Bills with CLCPA related costs disaggregated is the first admission by the Hochul Administration of potential costs of the Climate Act to ratepayers. The basis for the

typical electric delivery and supply bills for 2022 was provided for the following customer types:

A. Residential customers (600 kWh per month),

B. Non-residential customers (50 kW & 12,600 kWh per month),

C. Non-residential customers (2,000 kW & 720,000 kWh per month), and

D. Non-residential high load factor customers (2,000 kW & 1,296,000 kWh per month).

PSC Staff requested the utilities disaggregate the cost components reported in Table 2 (electric) to determine CLCPA related impacts on customers. Climate Act costs added between 9.8% and 3.7% to residential monthly electric bills in 2022.

Table 8: Authorized Funding to Date “gives a sense” of expenditures that will ultimately be recovered in rates. The Implementation Report explains:

This annual report is a review of actual costs incurred by ratepayers to date in support of various programs and projects to implement the CLCPA and does not fully capture potential future expenditures, including estimated costs already authorized by the Commission but not yet recovered in rates. To complement this overview of cost recoveries incurred to date, we also present below a table of the various programs and the total amount of estimated costs associated with each authorized by the Commission to date. Table 8 gives a sense of expenditures that ratepayers could ultimately see recovered in rates. These values are conservative and reflect both past and prospective estimated costs.

It is important to note that the Commission authorized some of the estimated costs in Table 8 prior to CLCPA enactment and that the cost associated with these authorized programs will be recovered over several years to come, based on the implementation schedules for these projects or programs and will mitigate the cost impacts to ratepayers year over year. These estimated costs represent either total program budget, estimated total cost for the program over its duration, or costs incurred to date in support of the program. Additionally, these initiatives will result in a variety of other changes that will impact how much consumers pay for energy. A number of these would put downward pressure on costs, including benefits in the form of reduced energy usage and therefore reduced energy bills to consumers. The Department has also previously described market price effects that are a result of these investments. When load is reduced or more low-cost generation is added, it would be anticipated that energy prices would fall because the market would rely less on higher cost generators. In addition, investments in transmission infrastructure not only unbottle renewable energy but also yield production cost savings and reliability benefits.

In sum, the total estimated costs associated with these programs or projects should not be considered as entirely incremental costs to what ratepayers would otherwise pay. Subsequent annual reports may include additional information about costs recovered relative to the funding previously authorized by the Commission in these programs, including funds already expended in support of these programs.

The takeaway message from Table 8 is that the authorized funding to date of program costs that will eventually make their way to ratepayer bills totals $43.756 billion. Note that the spreadsheet version of this table details the footnote costs.

The following table (Summary tab in the spreadsheet) combines Table 4: 2022 Electric CLCPA Recoveries and Table 8: Authorized Funding to Date. This represents my best estimates of where the cost categories coincide but it represents my opinion only. Given all the caveats in the preceding description I don’t think anyone has a definitive handle on these numbers. The thing that jumps out is the difference between the relatively paltry $1.176 billion in estimated Climate Act costs collected in 2022 relative to the $43.756 billion in authorized funding. Table 4 data is for one year and Table 8 data is over multiple years. The caveats in the previous quotation should be kept in mind.

Buried in a footnote is an admission that these are not all the costs authorized. Footnote 7 in Table 8 states:

Not included in this table is the Propel NY transmission project, selected by the NYISO Board in June 2023 in response to the Commission’s declaration of a public policy transmission need (PPTN) to support injections of offshore wind energy to the Long Island system by 2030 at an estimated cost of $3.36 billion. Since the Commission did not directly approve this project, the estimated cost is not captured in the table above.

The bottom line is that this is just the start of the costs. The Propel transmission project is one example. I described this project and its costs earlier this year. I noted that the costs associated with this project are for 3,000 MW of offshore wind. The Climate Act goal is for 9,000 MW and the Scoping Plan Integration Analysis projects that 12,675 MW of offshore wind will be needed by 2040 in the Strategic Use of Low-Carbon Fuels mitigation scenario. If the transmission costs are proportional that would mean that transmission costs will be three to four times higher than the $3.36 billion listed for the program that is not included. I am sure that there are many more examples of programs that will be needed to satisfy the regulated utility obligations for Climate Act emission reduction mandates.

NYCI Reference Case Scenario

The proposed modeling methodology for NYCI proposes to follow the same policy modeling approach as the Scoping Plan where a business-as-usual baseline is not used as the comparison standard for the policy scenarios. Instead, they propose to use the Scoping Plan Reference Case described as “Business as usual plus implemented policies” that includes the following:

- Growth in housing units, population, commercial square footage, and GDP

- Federal appliance standards

- Economic fuel switching

- New York State bioheat mandate

- Estimate of New Efficiency, New York Energy Efficiency achieved by funded programs: HCR+NYPA, DPS (IOUs), LIPA, NYSERDA CEF (assumes market transformation maintains level of efficiency and electrification post-2025)

- Funded building electrification (4% HP stock share by 2030)

- Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards

- Zero-emission vehicle mandate (8% LDV ZEV stock share by 2030)

- Clean Energy Standard (70×30), including technology carveouts: (6 GW of behind-the-meter solar by 2025, 3 GW of battery storage by 2030, 9 GW of offshore wind by 2035, 1.25 GW of Tier 4 renewables by 2030)

Business-as-usual in my opinion should only include: growth in housing units, population, commercial square footage, and GDP; Federal appliance standards; and economic fuel switching. All the other programs only exist as part of electrification strategies to reduce GHG emissions.

The Analysis Inputs and Methods webinar presentation stated that the Scoping Plan’s Reference Case will be updated with policies adopted since the original modeling was completed. The webinar asked for input on which policies to include from the following list:

- NYC Local Laws

- Statewide new construction codes

- IRA Incentives

- Advanced Clean Cars II/Advanced Clean Trucks

- 100% sales MHDVs by 2045

- 100% ZEV school buses by 2035, 100% transit buses by 2040

- IRA Methane Charge

- EPA Supplemental Rule

- NYS Part 203

- AIM Act (EPA Technology Transitions)

All of these programs also exist solely to reduce GHG emissions. In order to determine the cost to meet the Climate Act targets they should be included as part of the policy case and not the business-as-usual case.

It can be argued that every line item in Table 8 could be considered part of the proposed Reference Case because some component of each category started before the Climate Act was enacted. Recall that the Informational Report did not try to differentiate between pre-Climate Act and post-Climate Act programs so there are portions of the programs listed that will likely not be considered appropriate for the reference case. However, using this definition most of these costs will be in the reference case and I would bet that the rationale and costs will not be documented well enough to determine which specific control programs are included.

One other way to differentiate between pre-Climate Act and post-Climate Act enactment is by the case number. The first two digits are the year the proceeding began. In my summary table there is only one case number 20 or higher. Strategic Use of Energy Related Data (Case 20-M-0082) has $72 million funding authorized to date. Using this approach, the proposed Reference Case would include $43.684 billion program costs as opposed to the $43.756 billion of total authorized costs. I believe that they can pick and choose programs to include or exclude based on this reference case approach to satisfy the political motivations of the Hochul Administration.

Discussion

The Scoping Plan has been described as “a true masterpiece in how to hide what is important under an avalanche of words designed to make people never want to read it”. The quantitative documentation supporting the document hides relevant information even better. The single number that most New Yorkers want to know is how much will this cost. The Scoping Plan cost numbers did not answer that question.

I addressed the Scoping Plan cost and benefit numbers in my Draft Scoping Plan comments and the verbal comments I presented at the Syracuse public hearing. The issues I raised and summarized in this post have never been addressed. In that post I compared the Scoping Plan cost presentation to a shell game. A shell game is defined as “A fraud or deception perpetrated by shifting conspicuous things to hide something else.” In the Scoping Plan shell game, the authors argue that energy costs in New York are needed to maintain business as usual infrastructure even without decarbonization policies but then include decarbonization costs for “already implemented” programs in the Reference Case baseline contrary to standard operating procedure for this kind of modeling. Shifting legitimate decarbonization costs to the Reference Case because they are already implemented without adequate documentation fits the shifting condition of the shell game deception definition perfectly.

Anyone who has not spent much time following the Climate Act implementation process might ask why was this done for the Scoping Plan analysis and why is it being proposed for the NYCI modeling analysis. One of the justifications for the Scoping Plan was that the “costs of inaction are more than the costs of action”. Shifting implementation costs away from the Climate Act program reduced the costs of actions to the point that they could make that claim.

Why are they doing it again? One of the great unknowns in the NYCI implementation process is the revenue target. The rational approach would be to calculate expected total costs, revenues from Federal programs, revenues from utility ratepayers, and personal and business investments for required infrastructure then calculate the difference between costs and those revenues as the amount necessary for the cap-and-invest revenues. Each of those values is a politically sensitive number that will likely cause public outcry because it is going to be large. If the NYCI revenue target does not include all the costs necessary to meet the Climate Act targets because those costs are covered elsewhere, then the NYCI modeling can show that the program is “affordable” and will not be a major burden. Given that this strategy worked for the Scoping Plan “costs of inaction are less then the costs of action” scam I believe they are sticking with a proven strategy.

Conclusion

This past week there were signs of discontent with the potential costs of the Climate Act on utility ratepayer assessments. Utility bills in New York City will go up significantly next month when Consolidated Edison of New York’s new rate case assessments become effective. Con Ed admitted that renewable energy investments contributed to the cost increases. “Our customers demand safe and reliable service and increasingly renewable energy. This investment from customers is going to allow us to redesign and rebuild the grid, to move it towards electrification,” Con Ed media relations director Jamie McShane told Fox News Digital.

Comparison of the two state initiatives indicate that these costs are going to get much worse. The PSC Implementation Report states “The magnitude of change the CLCPA requires is significant and will present challenges related to the need to preserve the resiliency and reliability of the energy systems, and cost mitigation to preserve energy affordability”. The NYCI modeling assessment proposes to use an inappropriate modeling scenario that hides the true costs of implementation. I have little doubt that the Hochul Administration analysis team has already determined that this approach is necessary to provide a politically correct NYCI revenue target.

At this point all anyone can do is to ask for a full accounting of the costs and expected emission reductions for all the control strategies necessary to meet the net-zero Climate Act mandate. This information was not provided in the Scoping Plan but is a prerequisite for the proposed NYCI program.

Finally, note that the costs addressed in the PSC proceeding are ratepayer costs for energy. The overall strategy for de-carbonization is to electrify everything possible. The costs for each homeowner to replace their furnace, stove, and hot water heater with an electrical replacement is not included. There also will be homeowner costs associated with electric vehicles to say nothing of the cost of electric vehicle itself. When everything is added up the costs will be enormous. I do not think that customer demand for renewable energy is as strong as the desire for affordable energy. It is past time for the Hochul Administration to supply a full accounting of potential costs to residents and businesses so that people will be able to decide for themselves how much they want to pay.