This post summarizes comments I submitted to the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) in response to a request for feedback on “additional updates to the guidance to align methodologies with recent updates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.”

I have followed the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act)since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 400 articles about New York’s net-zero transitionThe opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. It includes an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% reduction by 2030 and a requirement that all electricity generated be “zero-emissions” by 2040. The Climate Action Council (CAC) was responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlined how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” In brief, that plan is to electrify everything possible using zero-emissions electricity. The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to develop the Draft Scoping Plan outline of strategies. After a year-long review, the Scoping Plan was finalized at the end of 2022. Since then, there have been regulatory and legislative initiatives to implement the recommendations, but progress has been slow.

The value of carbon requirement was one of the first initiatives. Four years ago, I published an article on section § 75-0113 of the Climate Act. That section explicitly mandates how the value of carbon will be determined:

- No later than one year after the effective date of this article, the department, in consultation with the New York state energy research and development authority, shall establish a social cost of carbon for use by state agencies, expressed in terms of dollars per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent.

- The social cost of carbon shall serve as a monetary estimate of the value of not emitting a ton of greenhouse gas emissions. As determined by the department, the social cost of carbon may be based on marginal greenhouse gas abatement costs or on the global economic, environmental, and social impacts of emitting a marginal ton of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, utilizing a range of appropriate discount rates, including a rate of zero.

- In developing the social cost of carbon, the department shall consider prior or existing estimates of the social cost of carbon issued or adopted by the federal government, appropriate international bodies, or other appropriate and reputable scientific organizations.

The DEC published the calculation methodology as mandated and has since updated New York’s Value of Carbon Guidance. The DEC Climate Change Guidance Documents webpage notes that it was established for use by State entities to “aid decision-making and for the State to demonstrate the global societal value of actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in line with the requirements of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.” It includes an Appendix that provides social cost values for the greenhouse gases incorporated into the Climate Act. Also note that the documents include a report by the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) and Resources for the Future that was used to determine the values used.

Comment Process

The bottom line is that the DEC goes through the motions for the comment process. I pretend that someone will listen when I comment, the agencies pretend to appreciate my comments but inevitably go on to do whatever fits the political narrative, and, in most cases, I never hear anything about my comments. There is a requirement that requires DEC to respond to comments for proposed regulations so at least I get some feedback. It is not clear to me whether this request for feedback requires responses to comments received. When the original draft guidance was proposed DEC went through the regulatory process which included a formal comment period and required them to respond to comments. I described my November 2020 comments in a post and followed up with commentary on their response to my in January 2021.

As frustrated as I am with the DEC stakeholder process it is orders of magnitude better than the NYSERDA stakeholder process. Even when responses are not required, DEC staff acknowledges followup questions and sometimes answers them. I believe that they are also subject to intense political pressure to maintain the Administration’s narrative on all things climate-related. NYSERDA’s stakeholder process for the Scoping Plan consisted of a list of comments received and a heavily condensed and biased summary of the comments received. They consistently refuse to answer questions about technical issues or the resolution of comments received. I appreciate DEC staff for being open to discussion and condemn NYSERDA for ignoring stakeholders that do not agree with the political narrative.

Social Cost of Carbon Comment

Given the unlikelihood of any changes based on my comments, I did not spend a lot of time developing comments. Moreover, the request for feedback regarded using new information from EPA. Any attempt to argue that EPA got it wrong after EPA went through a similar process would have no chance of success.

Nonetheless I took the opportunity to argue that the societal value of greenhouse gas emission reductions approach is not in the public consciousness. I stated:

All the proposed changes will increase the value of greenhouse gas emission reductions. The contrived metric projects the benefits of reducing GHG emissions on future global warming impacts including those on agriculture, energy, and forestry, as well as sea-level rises, water resources, storms, biodiversity, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and vector-borne diseases (like malaria), and diarrhea. Richard Tol describes the value of greenhouse gas emission reductions thusly: “In sum, the causal chain from carbon dioxide emission to social cost of carbon is long, complex and contingent on human decisions that are at least partly unrelated to climate policy. The social cost of carbon is, at least in part, also the social cost of underinvestment in infectious disease, the social cost of institutional failure in coastal countries, and so on.”

The Request for Feedback notes that “the new approach to discounting addresses public concerns regarding intergenerational equity.” For the record I have two issues with these concerns. I do not believe that the public raised concerns about intergenerational equity. Instead, that concern was raised by climate activists and non-governmental organizations whose monomaniacal focus on the alleged existential threat of climate change disregards any tradeoffs between costs, reliability, and environmental impacts of their favored solutions and the contrived benefits they claim. The second issue is that the public is unaware of these contrived calculations. If they were aware that New York’s Value of Carbon calculations project alleged impacts out to 2300, I am sure that they would wonder about the impacts today relative to those ten generations in the future. They would not look kindly at the hubris involved with claims that we can predict or even imagine what the world would like 275 years in the future. Moreover, Bjorn Lomborg notes in his 2020 book False Alarm – How Climate Change Panic Costs Us Trillions, Hurts the Poor, and Fails to Fix the Planet (Basic Books, New York, NY ISBN 978-1-5416-4746-6, 305pp.) that the costs of global warming will only reach 2.6% of GDP by 2100 but that global GDP will be so much higher at that time that this number is insignificant.

A recent article by Alex Trembath gives another take about why this metric is troubling. In response to his views about the social cost of carbon he did not want to disregard it entirely but said:

fundamentally, impossible. And it’s not just the fat tails of climate risk distribution, the controversies about the discount rate, or the other long-standing hurdles to a more robust SCC consensus. It’s that climate change is a slow-moving and massively complex global threat. We simply have no access to essential information, such as the size of the global economy decades from now and its resilience to climate impacts or even the exact sensitivity of the climate to emissions, that would inform a robust cost-benefit analysis.

Substantive Comment

I only made one substantive comment on the Value of Carbon methodology. I make this comment every chance I get and so far, have not been able to get a change. In short, I am convinced that the State calculation methodology is incorrect.

My comment addresses the “Estimating the emission reduction benefits of a plan or goal” section in the 2023 version of the Value of Carbon Guideline that states:

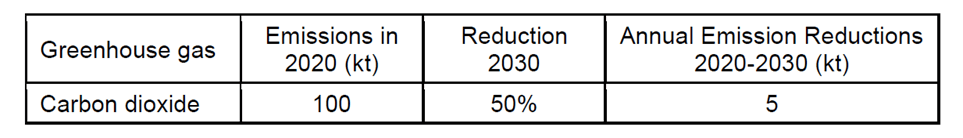

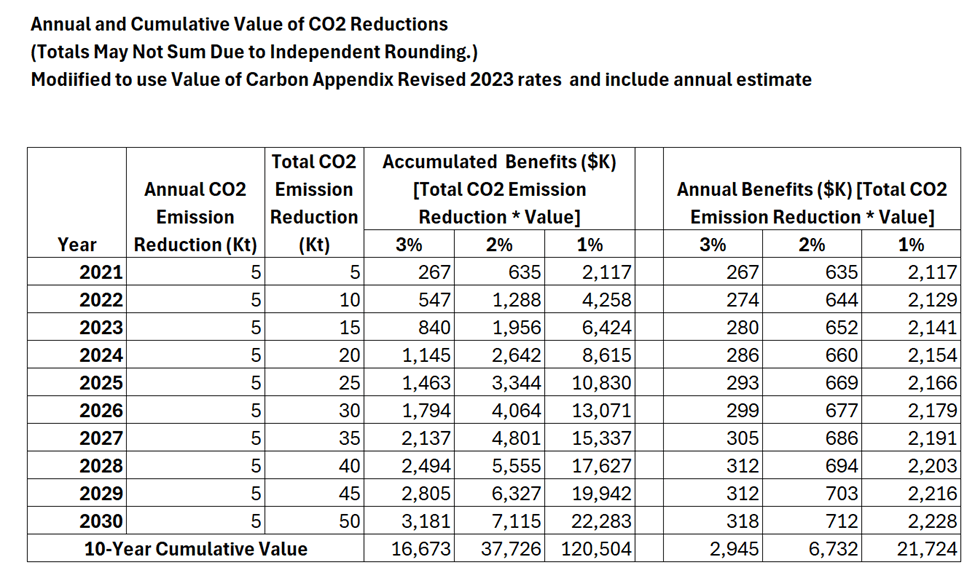

Estimating the emission reduction benefits of a plan or goal. An agency has developed a strategic plan with the goal of reducing carbon dioxide emissions 50% over ten years from current levels, or 50,000 metric tons over 10 years. In order to determine the benefits to society in terms of avoided damages, the agency will need to determine the annual level of emission reductions (or emissions avoided) compared to a no action scenario. If split evenly across all 10 years, the annual reduction is 5,000 metric tons per year (see table).

The net present value of the plan is equal to the cumulative benefit of the emission reductions that happened each year (adjusted for the discount rate). In other words, the value of carbon is applied to each year, based on the reduction from the no action case, 100,000 tons in this case. The Appendix provides the value of carbon for each year. For example, the social cost of carbon dioxide in 2021 at a 2% discount rate is $123 per metric ton. The value of the reductions in 2021 are equal to $123 times 5,000 metric tons, or $615,000; in 2022 $124 times 10,000 tons, etc. This calculation would be carried out for each year and for each discount rate of interest. The results for all three recommended discount rates are provided below. [The table below modifies the Guidance document with updated values of carbon and the correct annual benefits.]

My comments noted that the Climate Act mandates an 85% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2050. I believe that New York’s Value of Carbon should be applied in the context of the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions necessary to meet that goal. In particular, the reduction in annual emissions year to year. In this context, I believe that the guidance approach is wrong because it applies the social cost multiple times for each ton reduced. It is inappropriate to claim the benefits of an annual reduction of a ton of greenhouse gas over any lifetime or to compare it with avoided emissions. As shown above, the Value of Carbon methodology sums project benefits for every year for some unspecified lifetime subsequent to the year the reductions. The value of carbon for an emission reduction is based on all the damages that occur from the year that ton of carbon is reduced out to 2300. Clearly, using cumulative values for this parameter is incorrect because it counts those values over and over. I contact social cost of carbon expert Dr. Richard Tol about my interpretaton of the lifetime savings approach and he confirmed that “The SCC should not be compared to life-time savings or life-time costs (unless the project life is one year)”.

The preceding table calculates the benefits of the example project correctly. Note that if done correctly that the projected benefits are at least 5.5 times less than the in the flawed Value of Carbon methodology.

As mentioned before, although I am frustrated by the DEC stakeholder process, I did manage to get DEC staff to define their position on this topic. As I described in another article, I wrote to DEC and Climate Action Council about this problem in the guidance document. I received the following response:

We did consider your comments and discussed them with NYSERDA and RFF. We ultimately decided to stay with the recommendation of applying the Value of Carbon as described in the guidance as that is consistent with how it is applied in benefit-cost analyses at the state and federal level.

When applying the Value of Carbon, we are not looking at the lifetime benefits rather, we are looking at it in the context of the time frame for a proposed policy in comparison to a baseline. Our guidance provides examples of how this could be applied. For example, the first example application is a project that reduces emissions 5,000 metric tons a year over 10 years. In the second year you would multiply the Value of Carbon times 10,000 metric tons because although 5,000 metric tons were reduced the year before, emissions in year 2 are 10,000 metric tons lower compared to the baseline where no policy was implemented. You follow this same methodology for each year of the program and then take the net present value for each year to get the total net present value for the project. If you were to only use the marginal emissions reduction each year, you would be ignoring the difference from the baseline which is what a benefit-cost analysis is supposed to be comparing the policy to.

The integration analysis will apply the Value of Carbon in a similar manner as it compares the policies under consideration in comparison with a baseline of no-action.

I should have explicitly referenced this in my comments. It does not address my primary concern that the proper cost-benefit analysis is for meeting the Climate Act mandated target of an 85% reduction in GHG since 1990. Moreover, the benefit-cost analysis argument further biases their societal benefit claims when numbers are presented to the public.

Conclusion

To justify implementation of the Climate Act, the Hochul Administration political narrative is “that the costs of inaction are more than the costs of action”. The Scoping Plan basis for the claim included air quality health benefits, active transportation, and energy efficiency interventions in low- and middle-income homes. These benefits were not large enough to prove the case. The largest benefits claimed were based on the value of carbon avoided cost of GHG emissions. Absent the incorrect value of carbon methodology, the costs of action are more than the costs of inaction. I submitted this as a Scoping Plan comment and made the comment in a public hearing but have never received any response.

I do not expect any meaningful response to these comments. Most disappointing however is that despite my documentation of this error and other shenanigans used by the Scoping Plan authors to make sure they could claim benefits were greater than costs there has never been any response to them. Perhaps they hope that ignoring it means that it will just go away. It is not for a lack of trying but trying to shift the political narrative of New York’s climate policy is unlikely to succeed. It does give me something to do in retirement though.