A recent article of mine summarized analyses describing a new category of generating resources called Dispatchable Emissions-Free Resources (DEFR) necessary for a future grid that depends upon wind, solar, and energy storage resources. Most analysts of the future New York electric system agree that new technologies are necessary to keep the lights on during periods of extended low wind and solar resource availability. This article describes Appendix F – Dispatchable Emission-Free Resources in the New York Independent System Operator 2023-2042 System & Resource Outlook (“Outlook”).

I have followed the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act)since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 450 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. It includes an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% reduction. Two targets address the electric sector: 70% of the electricity must come from renewable energy by 2030 and a requirement that all electricity generated be “zero-emissions” resources by 2040. The Climate Action Council (CAC) was responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlined how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to develop the Draft Scoping Plan outline of strategies. After a year-long review, the Scoping Plan was finalized at the end of 2022. Since then, the State has been trying to implement the Scoping Plan recommendations through regulations, proceedings, and legislation.

Dispatchable Emissions-Free Resources

In my Compendium of DEFR Analyses I summarized published posts describing DEFR that is highlighted as a concern in the NYISO Outlook. I described six analyses describing the need for DEFR: the Integration Analysis, New York Department of Public Service (DPS) Proceeding 15-E-0302 Technical Conference, NYISO Resource Outlook, Richard Ellenbogen, Cornell Biology and Environmental Engineering, and Nuclear New York.

The Overview in Appendix F – Dispatchable Emission-Free Resources describes the reason DEFR is needed:

Numerous studies have shown that a system comprised of intermittent renewable energy resources and short-duration storage (i.e. 4 and 8-hour capacity duration) that cycle daily can economically meet demand in most hours across a year.

Importantly NYISO is responsible for meeting demand at all times. Most of the time it is easy but there are times when it is not:

However, due to the seasonal mismatch in electricity demand and weather dependent production from wind and solar resources, there remains a significant amount of energy that must be shifted from the low net load intervals of the spring and fall seasons to the peak load times during the summer and winter months, as discussed in Appendix E: Renewable Profiles and Variability.

I described Appendix E previously. The data presented in Appendix E show that there are frequent periods when all the wind and solar resources are expected to provide much lower output than their rated capacity. It appears that planners must, at a minimum, account for a 36-hour period when all the land-based wind, offshore wind, and solar combined provide less than 10% of their rated capacity. The Overview goes on:

Advances in technological, economic, and modeling approaches are needed to better quantify and characterize the seasonal energy gap that remains to be served after the coordinated economic dispatch of renewables and storage resources. The NYISO seeks to improve the representation of this fleet segment in each of its successive study, while understanding that characterization of emerging technology implementation pathways can introduce its own uncertainty into the model. The NYISO continues to recognize that there is a need for supply beyond renewables and storage resources that can provide dependability supply during the summer and winter peak periods and when the output of renewable resources is low.

In the remainder of this article I will summarize the different sections of Appendix F – Dispatchable Emission-Free Resources.

Technologies

Appendix F in the Outlook evaluates three DEFR options that they believe represent the most likely viable approach but concede that there still are concerns even with these:

While DEFRs represent a broad range of potential options for future supply resources, two technology pathways being discussed as potential options for commercialization are: 1) utilization of low- or zero-carbon intensity hydrogen (typically generated by electrolysis derived from renewable generation) in new or retrofit combustion turbine or fuel cell applications or 2) advanced small modular nuclear reactors, which are currently seeking approval from the relevant regulatory bodies to design and operate these resources. Currently, both technologies have shown limited commercial viability on the proof of concept. Even assuming that they are commercially viable, there remains significant work in the implementation and logistics that must be overcome to economically justify transitioning the dispatchable fleet to some combination of new technologies in the next 15 years. Long-duration energy storage could potentially serve in the role of the modeled DEFRs in the Outlook. In many respects, long-duration energy storage closely mimics various hydrogen production and conversion pathways. Long-duration energy storage adds to load in many hours, similar to electrolysis production of hydrogen. However, a notable difference is that electrolysis production of hydrogen has a lower round-trip efficiency when injecting energy into the system compared to other long duration energy storage technologies under development.

I have a concern about these pathways. Hydrogen and advanced nuclear both “have shown limited commercial viability on the proof of concept”. Commercial viability is particularly important in New York’s deregulated environment because the State must entice some developers to risk an enormous amount of money to provide the necessary resources. Consider that “there remains significant work in the implementation and logistics that must be overcome to economically justify transitioning the dispatchable fleet to some combination of new technologies in the next 15 years”. As a result, I think the State is going to find it very difficult to convince anyone to take on the risk of either technology.

In its description of DEFR option Appendix F also notes “Understanding that many aspects of these technologies are currently unknown, and their capabilities and characteristics could change as more experience is gained, there is no standout leader among the options”. It goes on to conclude that “that a combination of resources and approaches will be needed to serve the role of the DEFR fleet”.

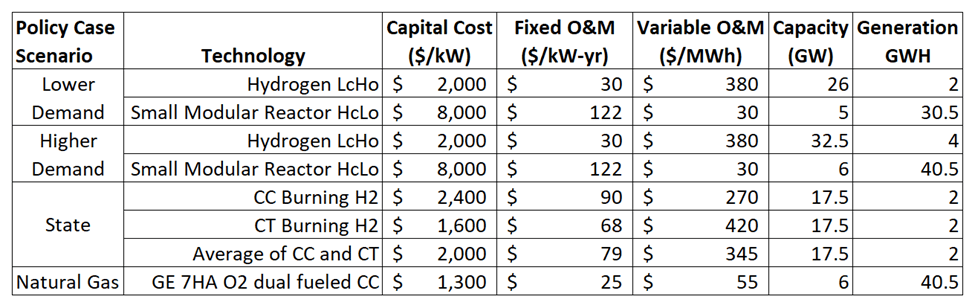

The Resource Outlook provides projections for future generating resources, so it needs to include some technology options. To fulfil this need and consider the uncertainties, the Outlook “modeled several generic DEFRs to represent the range of potential capital and operating costs. In particular, the Low Capital/High Operating cost (LcHo) and High Capital/Low Operating cost (HcLo) DEFRs modeled in this Outlook are informed primarily by hydrogen and nuclear technologies, respectively.”

Capital and Operating Costs

The models that NYISO uses to project future generating resource requirements necessarily incorporate costs. The capital and operating cost DEFR labels refer to high and low values but those are relative costs. This section of Appendix F provides some indications of costs but does not include expected costs to the consumers in the report. I think this information is very important, so I plan to return to this topic in a future post.

Because DEFR technologies are still in development the NYISO cannot use historical cost data. Instead, they used information from six different sources to estimate costs. The results are presented in the two following figures.

Figure F-1: Generator Capital Cost vs. Variable Operating & Maintenance, Fuel, and Emissions Costs

Figure F-2: Generator Capital Cost vs Fixed Operating & Maintenance Costs

I have also included a graph of Dispatchable Emission-Free Resources: 2040 Capacity and Generation from the NYISO Public Information Session presentation on 8/8/24

For what it is worth the following table provides values for the DEFR costs from these three figures. As noted, I will try to use these numbers to provide cost estimates in the future. Regrettably the NYISO report does not provide specific numbers.

DEFR Cost Considerations

This section in Appendix F presented some of the factors that must be addressed when considering costs. It explains that “since DEFRs are a developing technology, the first units built will likely be more expensive compared to similar DEFRs built thereafter”. The Outlook used capital costs representing a mature deployment and “first-of-a-kind costs are not explicitly included as assumed cost components in this study”. As the Outlook points out this means that “the costs for DEFRs in this Outlook are likely to be below the actual costs of the first DEFRs built on the system.”

The Outlook points out that nuclear small modular reactors (SMRs) are a “developing technology and therefore, have varying approaches to their design”. The theory is that “SMRs have the potential of reducing cost through the development and use of uniform designs”. Although this will lower capital costs capital costs will still be higher than other technologies. The expectation for DEFRs is that they will have low operating times and will ramp up and down. The Outlook notes:

Like large-scale nuclear power plants, SMRs can mitigate the risk of high capital costs with lower operating costs and operating with high utilization rates. In other words, it is optimal for an SMR to consistently operate at 100% power to take advantage of its low operating cost. This has the potential to conflict with the notion of DEFRs being used for their ability to dispatch up and down based on variability in the load. The disconnect between a DEFR’s purpose and an SMR can be bridged by pairing the reactor with a behind-the-meter, dispatchable load. The SMR can remain at 100% power, while the behind-the-meter load dispatches up or down to effectively fluctuate the injection onto the grid, as needed.

Unsaid is the obvious alternative that if SMT nuclear is viable then it could be used to replace renewables rather than just provide backup support. Nuclear energy generates zero-emissions electricity, provides firm power that does not require supplemental ancillary transmission support, has low land-use requirements, and requires less transmission development than wind and solar. Going all in for nuclear would not eliminate the need for a peaking power source but it may be possible to use hydro for that purpose. In a rational world keeping existing dual-fueled peaking plants available for this purpose would be an option too.

The Outlook also addresses hydrogen:

Hydrogen-burning combustion turbines or combined cycle units have effective cost mitigation strategies as well. To minimize hydrogen transport costs, the electrolyzer can be sited at the same facility as the resource. This eliminates the need for using an expensive hydrogen pipeline to import the hydrogen from elsewhere in state or even out of state. Additionally, as fossil fuel burning combustion turbines and combined cycle units retire, their assets can be repurposed and retrofit to burn hydrogen as a fuel instead. This has the potential to be less expensive than building a brand-new resource since many elements of the combustion turbine or combined cycle power plants can be reused with limited modification.

One of the more difficult electric system reliability problems is specifical considerations for New York City (NYC). Specifically, there is a reliability requirement for in-city generation. The 1977 NYC blackout was caused by transmission shutdowns and the inability of generating stations within the city to supply necessary load. The reliability load specifies how much in-city generation must be available to replace the loss of transmission power. I bring this up because this issue has not been discussed regarding DEFR. There will have to be DEFR resources in NYC and if hydrogen is the chosen technology, then hydrogen will have to be stored within the city. Hydrogen is a colorless, odorless, explosive gas that is hard to store. What could go wrong.

Operating Parameters

This section describes how some technical parameters are defined and used. The heat rate parameter is a measure of production efficiency, the lower the heat rate the less energy used to produce electricity. Lower heat rate units operate more often. The text lists the values used in the analysis.

There also is a discussion on the need for DEFRs to meet specific requirements such as the ability to be dispatched to follow load. Existing nuclear power technologies in the US have not been used to provide this service. The discussion describes how this service could be provided in future nuclear power designs. It also notes that there is a possibility that future reactors could be re-fueled while online which is much different than today’s reactors that require significant outages to re-fuel.

Conclusion

The NYISO Resource Outlook chapter on DEFR provides further proof that new technology is in fact necessary for the future zero-emissions New York electric system mandated by the Climate Act. The Hochul Administration has not provided cost estimates for the overall transition. I believe that DEFR costs will be a particular problem because this resource is used as rare backup. This report provides some cost information but not enough to estimate expected costs.