The New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA ) recently announced the completion of its Zero by 40 Technoeconomic Assessment (Zero by 40 Report). The report directly addresses what I think is the biggest reliability risk of the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) net-zero electric system transition. I summarized the report in my previous post. This is a companion article that does not include the background information in the first article and just compares the technologies evaluated

I am convinced that implementation of the New York Climate Act net-zero mandates will do more harm than good if the future electric system relies only on wind, solar, and energy storage because of reliability and affordability risks. I have followed the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 600 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

The current focus of Climate Act implementation is on meeting the interim reduction target of a 40% GHG reduction by 2030 and the all electricity must be generated by “zero-emissions” resources by 2040 mandate. My previous post provides more background.

The previous post explains that the Zero by 40 report was prepared in response to the Public Service Commission (PSC) recognition that there is a “need for resources to ensure the reliability of the 2040 zero-emissions electric grid mandated by the Climate Act”. A May 2023 Order notes that the Climate Act directs the PSC to establish a program to ensure that the electric sector targets are achieved and explains that “there is a gap between the capabilities of existing renewable energy technology and expected future system reliability requirements.” It concludes: “This Order responds to the Petition and initiates a process to identify technologies that can close the gap between the capabilities of existing renewable energy technologies and future system reliability needs, and more broadly identify the actions needed to pursue attainment of the Zero Emission by 2040 Target.” This class of technologies has been dubbed Dispatchable Emissions-Free Resources (DEFR). This Zero by 40 Report responds to that order.

I acknowledge the use of Perplexity AI to generate a summary of the report used as an outline and to provide references included in this document.

Technologies Evaluated in the Zero by 40 Technoeconomic Assessment

I had originally planned only a second companion article about the implications to the Climate Act to my summary post but decided that I needed to describe the technologies too. Section 1.4 in the Zero by 40 Report describes the technologies evaluated:

This report evaluates potential resources that can provide firm energy and capacity in a zero-emissions power sector. The study examines seven technology categories that could serve as DEFRs. These technologies are grouped into three resource groups based on their expected operational characteristics. While some resources can be configured to serve different roles, these groupings reflect constraints on costs, emissions, and availability in New York State, which are discussed later in the report.

Low-capacity factor resources can be deployed during periods of high demand and low renewable generation, offering reliability, fast-ramping capabilities, and no duration limitations, assuming fuel availability, but are not operated as baseload units due to plant economics. Low-capacity factor Resources include:

- Hydrogen (H2)

- Renewable natural gas (RNG) and renewable diesel (RD)

High-capacity factor resources operate the majority of the year and can provide reliable baseload power, including power during challenging events, but are less suitable for fast ramping or frequent starts and stops. High-capacity factor resources include:

- Advanced nuclear

- Carbon capture and storage (CCS) on thermal plants

- Geothermal

Gap-rightsizing resources can help balance supply and demand to adjust the capacity gap. While they do not generate electricity directly, they enhance the utilization of other clean resources. Gap-rightsizing resources include:

- Long duration energy storage (LDES) – Note that this refers to interday storage 10-36 hours

- Virtual power plants (VPP)

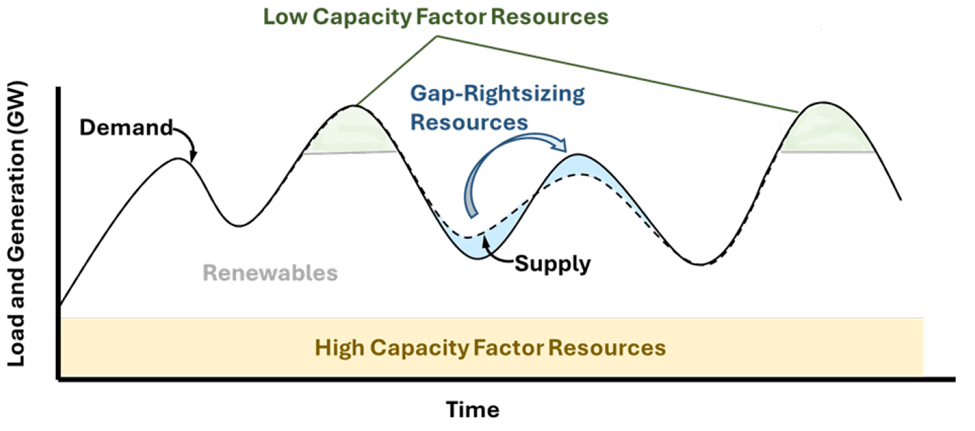

Figure 1 provides an illustrative example of the role of these different DEFR resource groups. While renewables play a significant role in overall power generation, the high-capacity factor resources supplement renewables by providing an additional source of baseload power. Low-capacity factor resources help to meet peak demand when renewables are insufficient. Gap-rightsizing resources can shift generation or load, increasing the value of renewable generation by mitigating intermittency to balance supply with demand.

Figure 1. Role of DEFR Resource Types in Meeting Electricity Demand

Source: New York State Energy and Research Development Authority (NYSERDA). 2025. “Zero by 40 Technoeconomic Assessment, Final Report.” Prepared by Electric Power Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA. Zero by 40 Technoeconomic Assessment

Operational Characteristics

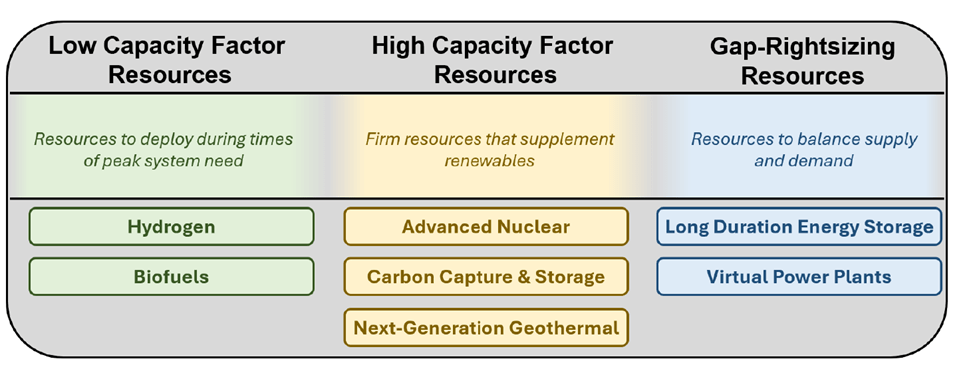

Figure 2 from the Zero by 2040 Report describes the characteristics of the three functional categories. It is instructive to consider these resources relative to three categories of generating resource production over time.

Figure 2. Functional Categories of DEFR Resource Types

Source: New York State Energy and Research Development Authority (NYSERDA). 2025. “Zero by 40 Technoeconomic Assessment, Final Report.” Prepared by Electric Power Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA. Zero by 40 Technoeconomic Assessment

Technology Assessment Technologies Summary

Chapter 9 in the Zero by 2040 report compares the potential DEFR technologies. The report uses the following criteria: performance attributes, readiness by 2040, infrastructure and supply chain readiness dynamics, project lead times, emissions and other considerations, cost, and scalability for 2040. Instead of looking at individual technologies the Chapter 9 summary describes the results for the three functional DEFR categories.

The Report describes Low-capacity factor resources as follows:

Low-capacity factor resources offer high flexibility and responsiveness to grid needs. They can be deployed during periods of high demand and low renewable generation, offering reliability and fast-ramping capabilities without duration limitations, assuming fuel availability. These resources are expected to be critical in any future zero-emission grid. However, they are expected to operate for only a limited number of hours per year due to a high operating-to-capital cost ratio, primarily driven by the cost of fuel, as well as fuel availability constraints. The low capacity factor resources evaluated in this study are H2, RNG, and RD.

The Low-Capacity resource summary states:

Low-capacity factor resources are expected to critical in any future zero-emission grid, offering reliability and fast-ramping capabilities on days with the most extreme system needs. Each technology evaluated has advantages and challenges. Infrastructure constraints and high costs may limit the widespread availability of H2 in 2040, but low GHG emissions, especially for green H2, will likely provide value across various industries in 2040 and beyond, making investments in pilot projects and eventual strategic infrastructure deployment important from an economywide perspective.

RNG and RD may be the most viable low-capacity factor resources for 2040 deployment given their technology readiness, existing fuel transport infrastructure, and ability to serve as drop-in fuels in existing plants. However, the combination of feedstock limitations, competition for fuels from other sectors and states, and GHG considerations necessitates limiting their use to low capacity factor applications.

High-capacity resources are described as follows:

High-capacity factor resources operate the majority of the year, providing reliable baseload power. These technologies can meet existing and growing load, reducing the need for both high-cost low-capacity factor DEFRs and some intermittent renewable deployment, often with a lower land footprint on a per-capacity basis. They also typically provide inertia and other ancillary grid services to support a grid increasingly dependent on variable renewables. While they have some ramping capabilities, they are less suitable for fast ramping or frequent starts and stops. This analysis compares LLWRs, lwSMRs, non-water-cooled reactors, NG combined cycle plants with 95% carbon capture and storage (CCS), and next-generation geothermal systems.

The High-Capacity resource summary states:

High-capacity factor resources are valuable for meeting existing load and expected load growth. While renewables are projected to supply most of the energy demand in 2040, high-capacity factor resources can provide firm power and grid services that support reliability in a predominantly renewable grid. Their high energy density also helps mitigate potential land-use challenges associated with large-scale renewable deployment. High-capacity factor resources could also reduce the need for low capacity factor resources, which are expensive and mostly idle. However, high-capacity factor resource technologies require long lead times, often 10 years or more. To ensure they are operational by 2040, stakeholders must take early action.

Each technology offers unique advantages and faces specific challenges. From a deployment-readiness perspective, LLWRs and CCS are the most prepared for near-term implementation. However, lwSMRs and non-water-cooled reactors could also become commercially viable by 2040. Geothermal, while promising, has lower readiness and limited scalability in New York State.

Gap-Rightsizing Resources are described as:

Gap-rightsizing resources help balance supply and demand, addressing the firm capacity gap. While these technologies do not generate electricity directly, they enhance the potential of other clean resources. They are expected to have significant value even today due to opportunities for energy arbitrage and infrastructure cost avoidance but will not be sufficient on their own to meet all grid needs due to duration limitations and because they do not generate electricity on their own. This study considers two main categories of Gap-Rightsizing Resources: LDES and VPPs. LDES includes mechanical, electrochemical, and thermal storage technologies. Within each of these buckets are several technologies with a range of attributes.

The Zero by 2040 report does not summarize this category. Both of the gap-rightsizing resources LDES and VPP are largely ready for deployment. Costs for VPP are lower than other technologies but depend on costumer participation which makes availability uncertain. Furthermore, there are limits to the energy potential of this technology. LDES batteries will be more expensive, but “has the potential for longer discharge durations and higher operational certainty, but it is also a net load on the grid due to the need to recharge and round trip efficiency losses.”

Discussion

There are two missing pieces to the path forward for the May 2023 Order. Someday some is going to have make recommendations about these technologies. The PSC needs another order specifying how it intends to “identify the actions needed to pursue attainment of the Zero Emission by 2040 Target”

The following caveat in Chapter 9 suggests the other component needed to move forward:

Most of the comparison focuses on comparing technologies within three resource groups: low capacity factor resources (hydrogen and biofuels), high capacity factor resources (advanced nuclear, carbon capture and storage, and next-generation geothermal), and gap-rightsizing resources (LDES and VPPs). Because technologies in different resource groups serve different functions, are expected to operate with very different profiles, and provide fundamentally different value to the grid, direct comparisons across resource groups are difficult and can be misleading. Ultimately, electric system modeling will be needed to understand the least-cost mix of resources and each of their potential unique contributions, which falls outside the scope of this study.

This report says more work is needed. It states that “electric system modeling will be needed to understand the least-cost mix of resources and each of their potential unique contributions, which falls outside the scope of this study.” In my opinion, it is not just the least-cost mix, but also the mix that minimizes reliability risks and environmental impacts. I think that New Yorkers need to know the impacts of this approach relative to impacts of continued use of fossil fuels, a lower-carbon approach that combines increased use of nuclear energy supplemented with fossil fuels where appropriate, and an all-in approach that uses nuclear as much as possible to reduce GHG emissions as much as possible. This report is committed to a mix of resources that includes massive amounts of wind, solar, and energy storage resources.

I also want to comment on the lack of urgency regarding this initiative. Responsible New York agencies all agree that the new Dispatchable Emissions-Free Resource (DEFR) technologies described in this report are needed to make a solar and wind-reliant electric energy system viable during extended periods of low wind and solar resource availability. Every day that a determination whether there is a viable DEFR approach is delayed means the costs, reliability risks, and environmental impacts associated with a wind and solar potentially false solution increase.

Conclusion

This is another reason that New York State needs to pause Climate Act implementation. The Legislature is required by a court decision to revisit the Climate Act to modify the schedule. It would also be appropriate for the politicians who insisted on this course of action to define affordability, reliability risk, and environmental impact boundary conditions that would frame a feasibility analysis be addressed. I further suggest that appropriate metrics be developed that ensure that implementation stops if those boundary conditions are exceeded. New Yorkers need to demand that the politicians who passed the Climate Act become accountable for its impact.