On December 6, 2025, I published an article describing my initial thoughts about the State Energy Planning Board (SEP) meeting on December 1 that discussed updated Pathways modeling for the State Energy Plan. This post describes the presentations at the meeting that covered energy affordability. I will cover the health benefits and employment analysis in another post.

I am convinced that implementation of the New York Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act or CLCPA) net-zero mandates will do more harm than good if the future electric system relies only on wind, solar, and energy storage because of reliability and affordability risks. I have followed the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 600 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Energy Plan Overview

According to the New York State Energy Plan website (Accessed 3/16/25):

The State Energy Plan is a comprehensive roadmap to build a clean, resilient, and affordable energy system for all New Yorkers. The Plan provides broad program and policy development direction to guide energy-related decision-making in the public and private sectors within New York State.

The New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) prepared the Draft Energy Plan last summer. Stakeholder comments were accepted until early October. The Energy Planning Board has the responsibility to approve the document. At the November 13, 2025 Board meeting there was a perfunctory description of the comments received. During the wrap up for this meeting Chair Doreen Harris said the Board will meet later this month to approve the plan before the end of the year. I have provided background information and a list of previous articles on my Energy Plan page.

Meeting Overview

There were three items on the agenda: approval of last meeting minutes, discuss analyses conducted for the Energy Plan, and consider any new business. The recording of the meeting available here included a transcript. I created an edited transcript for the Pathways Analysis presentation and a separate transcript for the energy affordability, health benefits, and employment presentations. These annotated versions include tables and headings.

In this meeting NYSERDA described the updated Pathways Analysis—the modeling exercise that underpins New York’s triennial State Energy Plan. In my opinion, the entire Energy Planning Board process is political theater. The members of the Board were chosen mostly for political reasons and not technical expertise. Everyone involved is going through the motions.

My last post explained that the updated Pathways Analysis described in the first part of this meeting found that the 2030 Climate Act goals will not be achieved on time. The aspirational schedule of the Climate Act was never realistic, and these results are simply acknowledgement of that fact. The topics featured in the remaining sessions support the positive spin narrative that the Hochul administration is trying to convey to the public to save some face regarding Climate Act implementation. This post will highlight key points of the narrative. I want to emphasize that this narrative is based mostly on political messaging, so it is appropriate to assume that every NYSERDA point has been approved by the Hochul Administration.

Energy Affordability

James Wilcox presented the Household Energy Affordability Analysis Update. He said that NYSERDA “reviewed key analysis structure and assumptions based on stakeholder feedback and new data availability”. The claim regarding review of stakeholder feedback is the first narrative speaking point. There will be a subsequent post detailing how New York State agency claim that all stakeholder feedback was considered is unsupported by evidence. While there are indications that some feedback from outside NYSERDA was incorporated in the updated analyses, later I will detail instances where comments inconsistent with the intended story line were ignored.

Wilcox summarized the updates:

- For Base Case, moved to an electric and gas price forecast based on the trend of total bills from bill history

- Added a higher energy price growth sensitivity based on the trend of total bills from recent bill history combined with recent DPS/utility projections

- Although numbers have shifted, key takeaways remain the same

- Net result from changes is a higher growth rate for electricity and gas rates

The affordability messaging has been consistent. NYSERDA acknowledges that there are energy affordability challenges. The Climate Act embeds environmental justice principles throughout its implementation framework, so descriptions include low- and moderate- income household impacts that are consistent with this narrative talking point, Unsurprisingly, those households are “more likely to experience energy affordability challenges”.

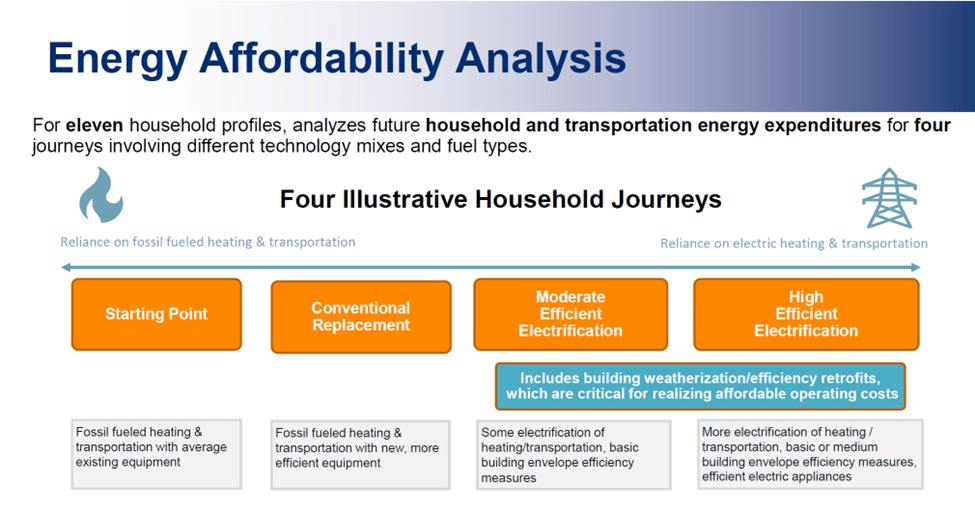

The following energy affordability analysis slide explains that for eleven household profiles, NYSERDA evaluated future household and transportation energy expenditures for four cases involving different technology mixes and fuel types. These “Illustrative Household Journeys” include:

- Starting Point: Fossil fueled heating and transportation with average existing equipment

- Conventional Replacement: Fossil fueled heating and transportation with new, more efficient equipment

- Moderate Efficient Electrification: Some electrification of heating and transportation, with basic building envelope efficiency measures

- High Efficient Electrification: More electrification of heating and transportation, with basic or medium building envelope efficiency measures, and efficient electric appliances

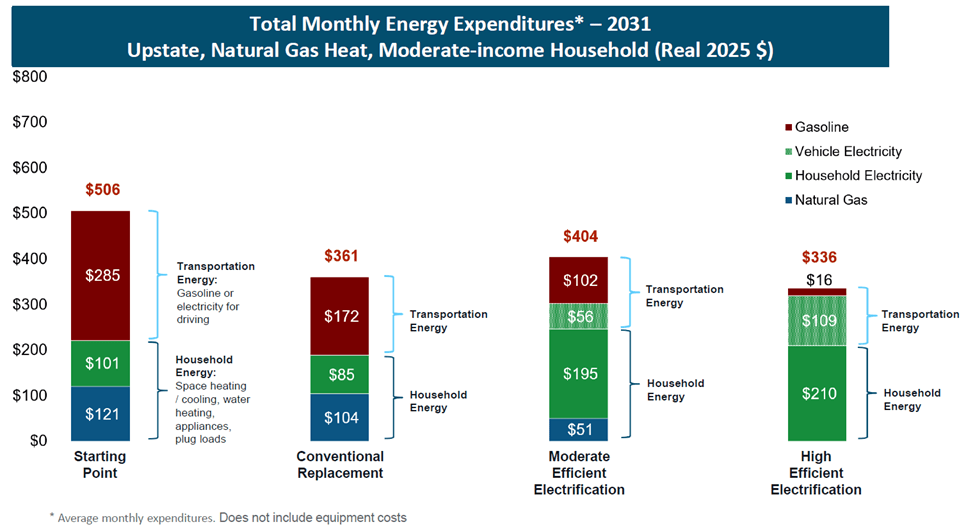

Slides were presented that describe the four journeys for several profiles. The following example describes monthly expenditures for a typical Upstate moderate-income household that uses natural gas for heat. Relative to the current starting point all three projected “household journeys” reduce monthly energy expenditures. However, buried at the bottom of the page is the notation that these values are “Average monthly expenditures. Does not include equipment costs”.

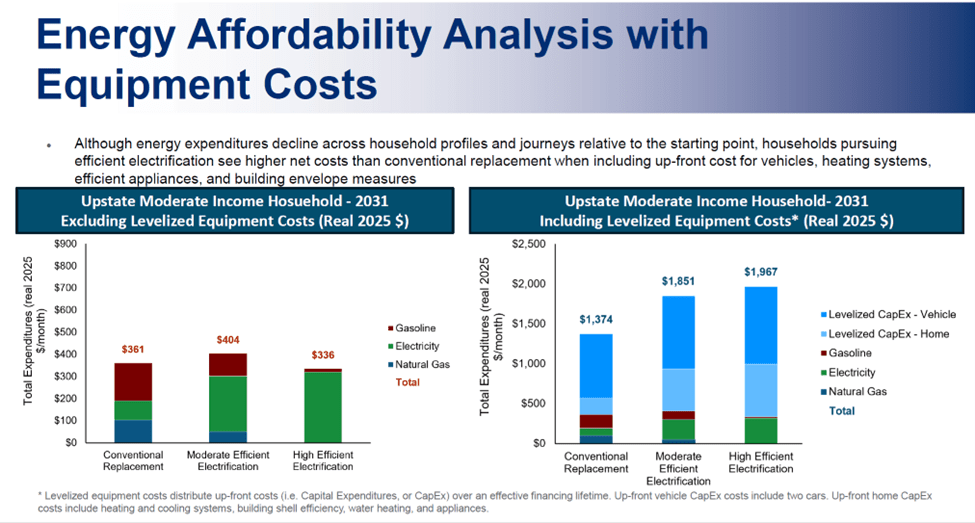

It turns out that including equipment costs makes a difference as shown in the next slide.

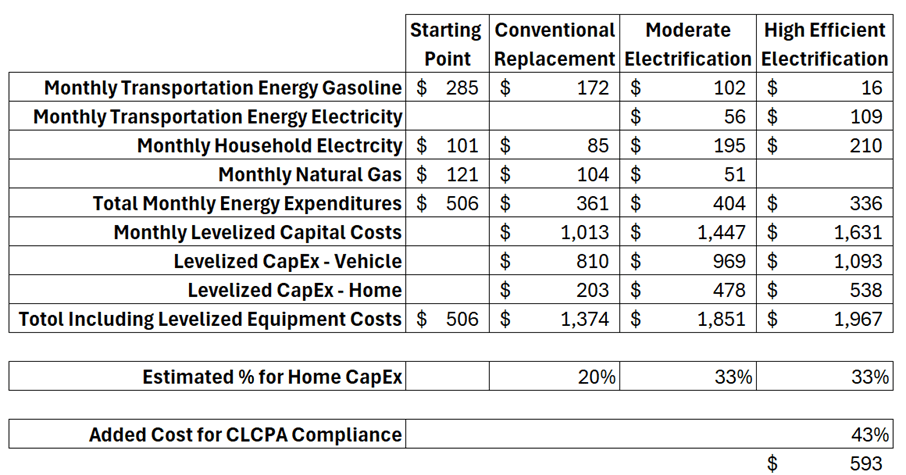

The Hochul/NYSERDA story is that monthly energy expenditures will go down when investments in moderate electrification or high efficiency electrification necessary for Climate Act compliance are made. The public release sound bite press releases will emphasize that point and barely acknowledge that the costs that include the capital expenses (CapEx) for the equipment costs tell a different story. I summarized all this information in Table 1. The first four rows list the monthly energy expenditures with the total in the fifth line. The CapEx monthly total cost is listed but the breakdown between the costs of a new plugin hybrid electric vehicle (moderate electrification) and a battery electric vehicle (high efficiency electrification) relative to home energy electrification is not provided. I estimated the percentage of home electrification from the bars in the previous figure. When those CapEx costs are included all the projected alternative journeys are more expensive. Note that the difference between replacement of conventional equipment and the highly efficient electrification equipment necessary for Climate Act compliance increases monthly average energy expenditures $593, a whopping 43% increase in energy costs. That is the cost of Climate Act compliance.

Table 1: Upstate New York Moderate Income Household That Uses Natural Gas for Heat Projected Monthly Costs and Costs Necessary to Comply with the Climate Act

The following key takeaways slide summarizes the messages that NYSERDA and Hochul want the Energy Planning Board and public to accept. The first statement suggests that if households continue to use existing equipment that energy spending will increase. But households “see gradually declining rates of energy consumption and total energy spending as more efficient equipment is adopted” then that “can help to offset energy price increases”. That advocates going forward despite a tacit acknowledgement that it may not save money, just reduce the increase. The final takeaway points out that according to their numbers transportation energy spending could offset incremental cost increases for home heating. I cannot overemphasize enough that results from this kind of modeling are completely dependent upon input assumptions. That means that the modelers can get any answer they want. It is therefore very telling that these takeaways cannot avoid the conclusion that the transition will incur significant costs. The modelers could not completely avoid reality.

Ultimately, the question is how much will all this cost. During his presentation Wilcox stated: “What we can take away is that the net costs for efficient electrification journeys could be 35% to 40% higher than conventional replacement when accounting for equipment, reinforcing the importance of action to address upfront equipment costs so that households are able to access the benefits of these systems.” NYSERDA is left hoping that there will be a magical solution that will reduce upfront costs so that the projections might be palatable.

The conclusions sums up the energy affordability messaging. There is an energy affordability problem that impacts low- and moderate-income households more with the implication that focus on those households will improve the situation. Energy costs impact both household and transportation spending. This needs to be emphasized because NYSERDA cannot claim monthly energy benefits for many household profiles if transportation costs are not included. Wilcox concludes the obvious point that “expected increases in energy prices highlight the importance of actions that can lower energy costs”. In my opinion the point that doing nothing is the least impactful action is not acknowledged. The importance of energy savings measures is highlighted. However, I don’t think this will provide as many benefits as they do because this has been emphasized for decades so the simple fixes and obvious solutions have already been implemented. It is easy to say that “Policy and market solutions that focus on lowering up-front costs” may make this more affordable, but no suggestions how that can be done or why anyone would expect that this may happen are offered. Finally, there is the recommendation of all analysts that have no clue how to get the preferred answer to “do further research”.

Presentation Discussion Topics

The annotated transcript for this presentation includes a heading for questions made during the meeting with a link to each person who commented or asked a question.

Chair Doreen Harris asked about the differences between Upstate and Downstate. Wilcox explained that there are climatic differences, transportation patterns are different, and the predominant type of housing is different. Harris followed up stating:

I think that’s important because that’s one of the reasons why we had to produce so many variations, right? Like, it reflects the diversity of our state in a way that means that the answer isn’t the same for everyone, depending on their own experience and the way they live.

Because I believe that this presentation was scripted to further the messaging of the Administration, I think it is telling that she wanted to emphasize impacts are not the same for everyone. I am not sure why, however.

The rationale for her second question about what happens if households do not upgrade is obvious. The projections show that all replacement scenarios doubles costs so doing nothing is an attractive option. Not only is that a great argument against an implementation schedule, but it establishes a significant public acceptance hurdle. Wilcox admitted that the key driver of change over the next five years is “change in energy price”. The modeling shows that this will increase household energy spending 3% to 8% in the starting point base case but could go up to as much as 14% to 19% even if they do nothing.

The questions and answers went on:

Harris: “And then, James, maybe to kind of take those percentages in context, was it in that higher price sensitivity, a household that did nothing could see as much as one hundred dollars a month increased costs. Is that about right?

Wilcox: “Yeah. That’s correct.”

Harris: “So there’s a substantial increase with these energy prices for folks who don’t take any action. Thank you. That is what I was trying to elicit: What does doing nothing get you?

To summarize, the Chair of the Energy Planning Board was trying to elicit a specific point from her staff that there will be a substantial increase in energy prices even if people don’t take any action. Her staff person Wilcox could have destroyed his career if he had pointed out that the minimum increase in any of the scenarios that replaced household and transportation equipment is 1.7 times greater than current costs which is far greater than the greatest impact of doing nothing which was 0.19 times greater.

After that the rest of the questions were a comedown. There were suggestions that the new technologies might offer new opportunities that might somehow, someway, mitigate the cold equations that show this is unaffordable. There was also a suggestion made that all would work out if New Yorkers used public transit.

Discussion

Presumably the Attorney General Office supplemental letter that argued that promulgating regulations for the Climate Act target would cause “undue harm” used in the New York Supreme Court litigation was developed with the assistance of NYSERDA. That letter claimed that the Climate Act mandates are infeasible due to excessive costs that are “unaffordable for consumers”. All these numbers confirm that there are affordability issues.

This finding sums up Climate Act affordability. For a moderate-income household in Upstate New York that uses natural gas the difference between replacement of conventional equipment and the highly efficient electrification equipment necessary for Climate Act compliance increases monthly average energy expenditures $593, a whopping 43% increase in energy costs.

There are ten other household profiles. The presentation did not provide sufficient information for a similar assessment of any of those other profiles. The State Energy Plan document web page does not list any updates to the draft materials from last summer so I am not able to develop an overview of all the household profile results. Also note that the documentation does not provide backup to the graphs and tables presented in the Energy Plan reports so this is no small task.

Conclusion

Any argument that the Climate Act transition will not be extraordinarily expensive can be refuted by using the data included in this presentation. Coupled with the Pathways Analysis presentation described previously that found that neither 2030 Climate Act target will be met before 2036, the only appropriate course of action is to reconsider the Climate Act. Given that it will require accountability by the politicians who got New York into this mess I am not optimistic.

One thought on “Energy Affordability at Energy Planning Board Meeting on 12/1/2025”