In my opinion the biggest problem with the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act or CLCPA) is that it will inevitably lead to extraordinary cost increases. My last article described the recent rate case decisions that have markedly increased residential customer electric bills. These rate increases arrive amid an escalating affordability crisis, as of December 2024, over 1.3 million households are behind on their energy bills by sixty-days-or-more, collectively owing more than $1.8 billion. This article documents unresolved affordability issues associated with the Climate Act.

I am convinced that implementation of the New York Climate Act net-zero mandates will do more harm than good if the future electric system relies only on wind, solar, and energy storage because of reliability and affordability risks. I have followed the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 600 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

There is a fundamental Climate Act implementation issue. Clearly there are bounds on what New York State ratepayers can afford and there are limits related to reliability risks for a system reliant on weather-dependent resources. The problem is that there are no criteria for acceptable affordability bounds.

Proponents of the Climate Act argue that the transition strategies in the law must be implemented to meet the net-zero mandates. However, they do not acknowledge that Public Service Law (PSL) Section 66-P, Establishment of a Renewable Energy Program, is also a law. PSL 66-P requires the Commission to establish a program to ensure the State meets the 2030 and 2040 Climate Act obligations. It includes provisions stating that the PSC is empowered to temporarily suspend or modify these obligations if, after conducting an appropriate hearing, it finds that PSL 66-P impedes the provision of safe, adequate, and affordable electric service. This requirement has been noted but, unfortunately, establishing a methodology to resolve the mandate has been ignored.

Petitions for a Hearing

The first unresolved affordability issue is the petitions by the Coalition for Safe and Reliable Energy and the Independent Intervenors submitted to PSC Proceeding Case 22-M-0149 that called for a hearing. There has been no indication by the PSC that they will respond to those petitions.

The recent filings argued that the PSC should convene a hearing. On August 11, 2025 “Independent Intervenors” Roger Caiazza, Richard Ellenbogen, Constatine Kontogiannis, and Francis Menton petitioned the PSC arguing that safety valve provisions for customers in arrears trends in PSL 66-p(4) have been exceeded which should trigger a hearing. On January 6, 2026 the Coalition for Safe and Reliable Energy filed a petition with the Public Service Commission (PSC) requesting that the Commission act expeditiously to hold a hearing pursuant to Public Service Law § 66-p (4). Both filings make similar arguments. The Independent Intervenors argued that there was an explicit requirement for the hearing because the customers in arrears threshold has been exceeded. The Coalition makes a persuasive argument that there are sufficient observed threats to reliability that a hearing is necessary to ensure safe and adequate service.

In addition, last summer two members of the Climate Action Council, Donna DeCarolis and Dennis Elsenbeck, sent a letter to Rory Christian, Chair & Chief Executive Officer of the New Yok State Public Service Commission (PSC) that made a similar argument that there are more than sufficient circumstances to warrant the PSC commencing a hearing process to “consider modification and extension of New York Renewable Energy Program timelines pursuant to Public Service Law § 66-p (4).

Agency Affordability Findings

There also have been New York Agency findings that argue that observed issues with schedule and costs suggest a pause to reconsider the mandates is appropriate.

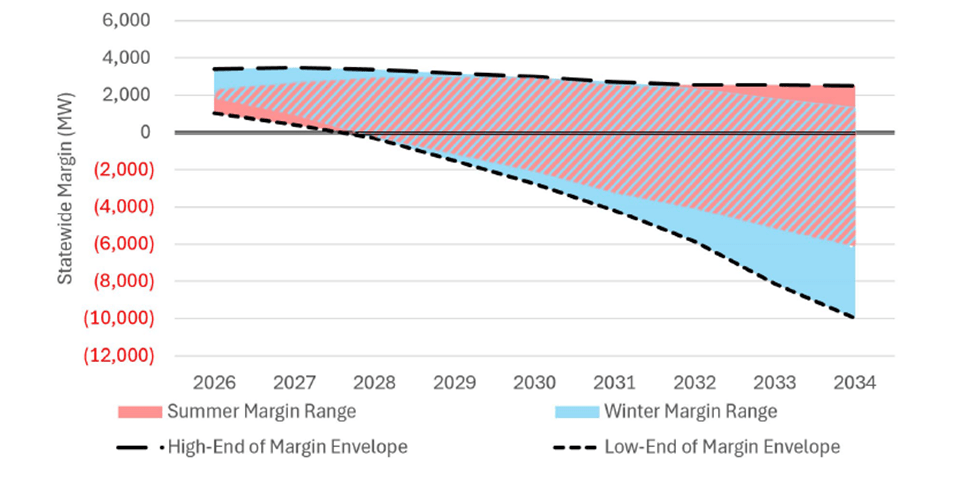

The Draft Clean Energy Standard Biennial Review prepared by Department of Public Service (DPS) Staff and NYSERDA “details the numerous factors, including inflation, transmission constraints, shifting federal energy and trade policies and interconnection and siting challenges that have adversely impacted renewable development and the state’s trajectory towards achieving the Program’s 2030 target.” The Biennial Review “concludes that a delay in achieving the 70% goal may be unavoidable.”

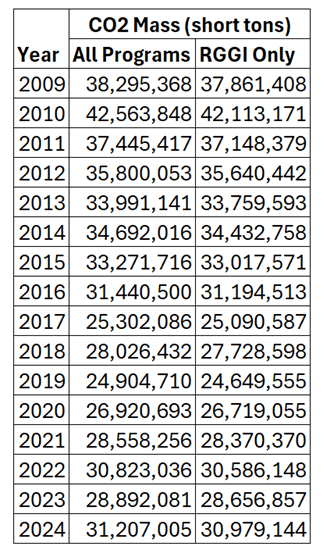

The recently completed New York State Energy Plan (SEP) found that “current renewable deployment trajectories are insufficient to meet statutory targets, and that external constraints continue to impede progress.” Volume 2 “Our Energy Systems” explains that “Considering resource build limitations and increased loads, the model aligns with the CES Biennial Review, projecting the procurement schedule of CES resources through 2035.” In other words, the SEP acknowledges that the Climate Act schedule is impossible to meet. The SEP found that Climate Act costs are expected to require $120 billion in annual energy system investments through 2040, equivalent to $1,282 per month per household. This baseline includes what the authors of the SEP characterizes as costs “no matter which future path we take” but I believe that framing is fundamentally deceptive because that scenario includes substantial greenhouse gas reduction programs implemented before 2019 that are necessary to meet the Climate Act goals.

The July 2024 New York State Comptroller Status report “Climate Act Goals – Planning, Procurements, and Progress Tracking” audited PSC and NYSERDA efforts to achieve the Climate Act mandates. It found that “While PSC and NYSERDA have taken considerable steps to plan for the transition to renewable energy in accordance with the Climate Act and CES, their plans did not comprise all essential components, including assessing risks to meeting goals and projecting costs.” The report recommended that the agencies begin the comprehensive review of the Climate Act, “continuously analyze” existing and emerging risks and known issues, conduct a detailed analysis of cost estimates, and “assess the extent to with ratepayers can reasonably assume the responsibility” of the implementation costs. This is the information necessary for the PSL 66-P hearing.

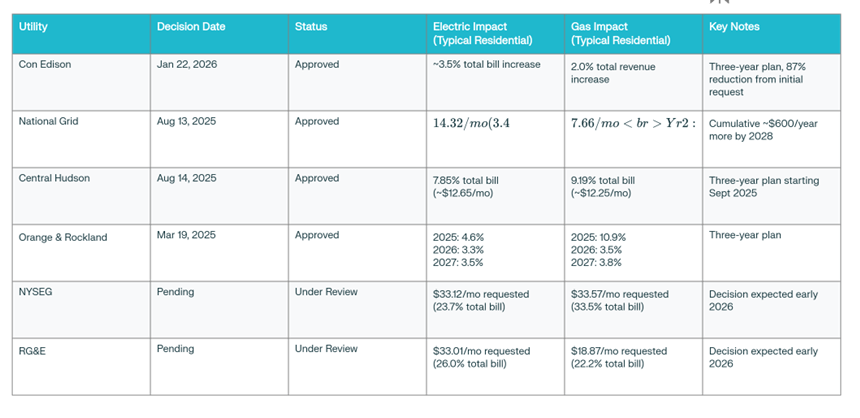

My last article summarized recent residential electric utility customers rate case decisions approved between March 2025 and January 2026. The New York Public Service Commission (PSC) “approved new multi-year rate plans for five major utilities—Con Edison, National Grid, Central Hudson, and Orange & Rockland—while two additional utilities (New York State Electric & Gas (NYSEG) and Rochester Gas & Electric (RG&E) have pending rate cases seeking significantly larger increases”.

Kris Martin from NY Solar Divide pointed out:

When we look at those modest Climate Act (CLCPA) percentages on “typical” electric bills, it’s important to understand that we have incurred only a small fraction of Climate Act expenses to date. The bulk of those expenses will really start to impact us in another 5-10 years as we start to seriously build out onshore and offshore wind and grid-scale solar, implement policy changes (e.g., school bus electrification), and deal with increases in demand.

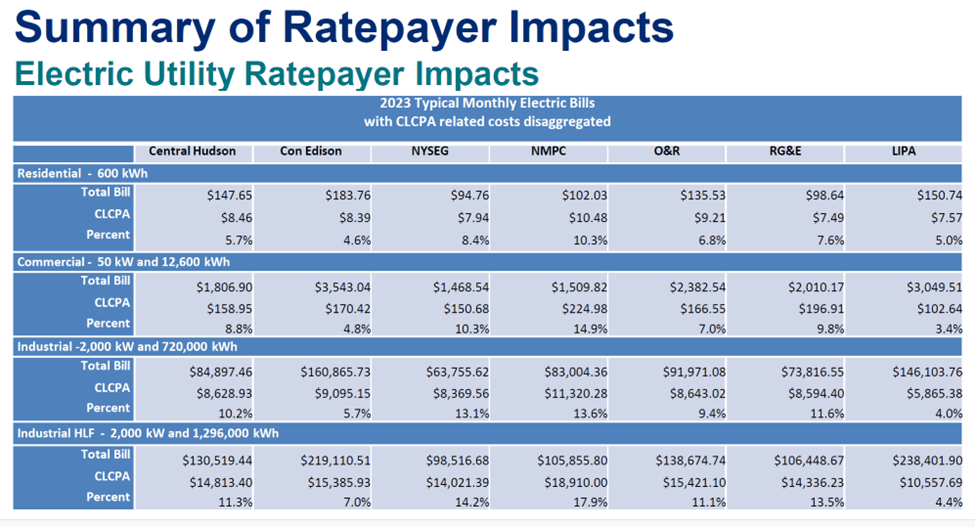

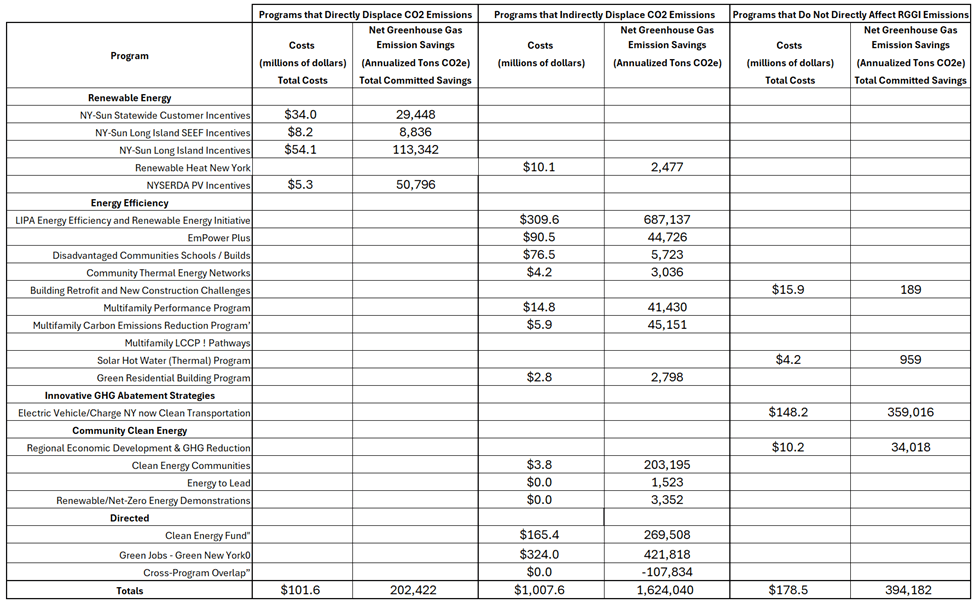

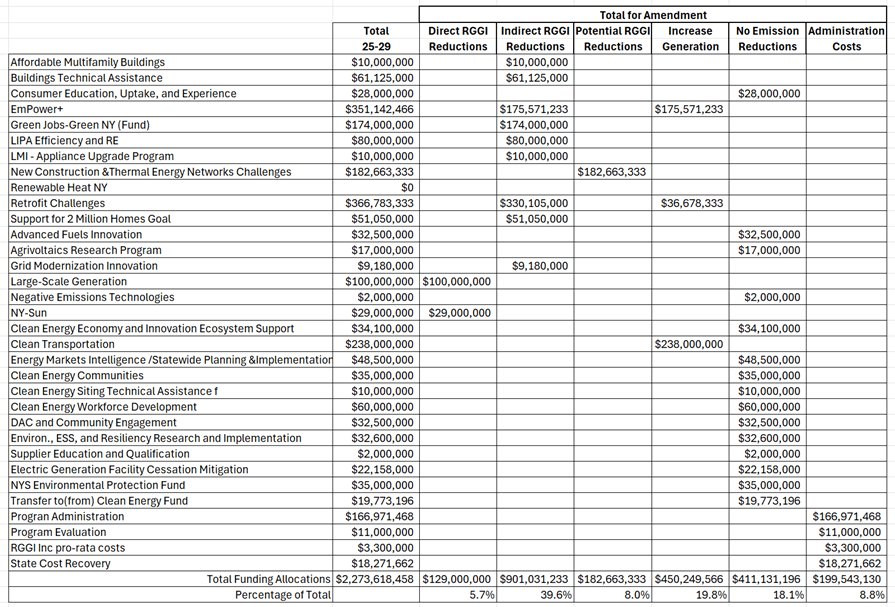

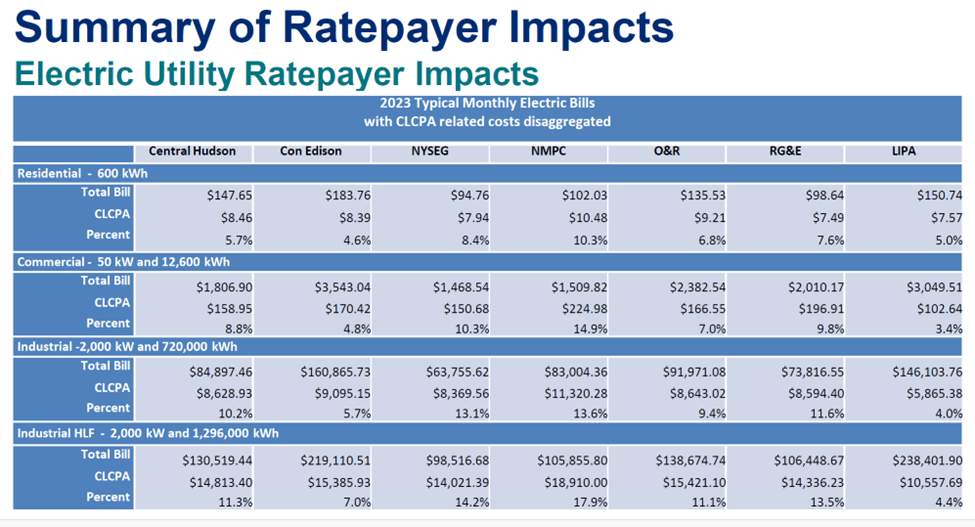

Department of Public Service (DPS) staff is supposed to provide Climate Act information. On September 18, 2025 the PSC announced that they “received an update from DPS staff regarding progress toward the clean energy goals of the Climate Act”. The Second Informational Report prepared by Department of Public Service (DPS) staff “focuses on Commission actions from January 2023 through August 2025, and includes the estimated costs and outcomes from 2023 through 2029 to provide the most up to date information.” According to the Summary of Ratepayer Impact for Electric Utilities table, residential impacts of the Climate Act range from 4.6% to 10.3% of 2023 total monthly electric bills. In my opinion, those estimates are conservative because there is immense pressure on agency staff to minimize the costs of the Climate Act. In addition, the costs necessary to implement the Climate Act were ramping up in 2023. As Martin notes these costs are just the tip of the iceberg.

Affordability Metrics

PSL law Section 66-p (4) states that the hearing could “temporarily suspend or modify the obligations” of the Renewable Energy Program if the PSC makes a finding that “there is a significant increase in arrears or service disconnections that the commission determines is related to the program”. This refers to affordability limits, but they are not specific enough. I believe the PSC must establish specific affordability limits.

This issue was also raised to the DPS last year. On March 26, 2025, Jessica Waldorf, Chief of Staff and Director of Policy Implementation for the Department of Public Service (DPS) posted a letter responding to a letter from Michael B. Mager Counsel to Multiple Intervenors that had been submitted earlier in March to Chair of the Public Service Commission Rory Christian regarding the affordability standard. I agreed with the comments submitted by Multiple Intevenors and was disappointed with the DPS response so I submitted a letter to Christian.

As described in my article My Comments on the NYS Affordability Standard: I believe that as part of the Scoping Plan the Climate Action Council should have developed criteria for the PSC to consider affordability and reliability. That did not happen. Based on issues observed with the transition it is incumbent upon the Commission to define “safe and adequate electric service” and “significant increase in arrears or service disconnections” as part of this Proceeding. My letter stated that this is necessary so that there is a clearly defined standard for the temporarily suspending or modifying the provisions of Section 66-p (4).

The Public Service Commission has an existing target energy burden set at or below 6 percent of household income for all low-income households in New York State. Reviewing it raises questions about its suitability for defining energy affordability acceptability.

The six percent target was included as part of Public Service Commission (PSC) Case Number: 14-M-0565, the Proceeding on Motion of the Commission to Examine Programs to Address Energy Affordability for Low Income Utility Customers. According to the PSC: “The primary purposes of the proceeding are to standardize utility low-income programs to reflect best practices where appropriate, streamline the regulatory process, and ensure consistency with the Commission’s statutory and policy objectives.” On May 20, 2016 the Order Adopting Low Income Program Modifications and Directing Utility Findings adopted “a policy that an energy burden at or below 6% of household income shall be the target level for all 2.3 million low income households in New York.”

The order notes that:

There is no universal measure of energy affordability; however, a widely accepted principle is that total shelter costs should not exceed 30% of income. For example, this percentage is often used by lenders to determine affordability of mortgage payments. It is further reasonable to expect that utility costs should not exceed 20% of shelter costs, leading to the conclusion that an affordable energy burden should be at or below 6% of household income (20% x 30% = 6%). A 6% energy burden is the target energy burden used for affordability programs in several states (e.g., New Jersey and Ohio), and thus appears to be reasonable. It also corresponds to what U.S. Energy Information Administration data reflects is the upper end of middle- and upper-income customer household energy burdens (generally in the range of 1 to 5%). The Commission therefore adopts a policy that an energy burden at or below 6% of household income shall be the target level for all low-income customers. The policy applies to customers who heat with electricity or natural gas.

The utility companies submit quarterly reports documenting the number of low-income customers receiving discounts and the amount of money distributed. However, I have been unable to find any documentation describing how many customers meet the 6% energy burden criteria, much less any information on how those numbers are changing. The biggest problem with this energy burden program is that it only applies to electric and gas utility customers. Citizens who heat with fuel oil, propane, or wood are not covered. Moreover, it only considers utility costs but the economy-wide provisions of the CLCPA include transportation energy burdens.

Clearly, if this parameter is to be used for a CLCPA affordability standard, then defining what is acceptable and what is not acceptable is necessary. Whatever affordability standard is chosen a clear reporting metric must be provided and frequent updates of the status of the implementation relative to the affordability standard provided.

It is also notable that Assistant Attorney General Meredith G. Lee-Clark submitted correspondence related to the litigation associated with Climate Act implementation. The State’s submittal to the petition addressed “two categories of new developments: (1) the publication of the 2025 Draft New York State Energy Plan by the New York State Energy Planning Board on July 23, 2025 and (2) additional actions by the federal government that impede New York’s efforts to achieve the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act’s (the Climate Act) goals in a timely manner.”

The submittal means that the State of New York argued that it was inappropriate to implement regulations that would ensure compliance with the 2030 40% reduction in GHG emissions Climate Act mandate because meeting the target is “currently infeasible”. The following paragraph concedes that there are significant upfront cost issues that out-weigh other benefits.

Ordering achievement of the 2030 target would equate to even higher costs than the net zero scenarios and would affect consumers even sooner. Undoubtedly, greenhouse-gas reducing policies can lead to longer-term benefits such as health improvements. This does not, however, offset the insurmountable upfront costs that New Yorkers would face if DEC were forced to try to achieve the Legislature’s aspirational emissions reductions by the 2030 deadline rather than proceeding at an ambitious but sustainable pace.

The letter concluded that the Climate Act is unaffordable:

Petitioners have not shown a plausible scenario where the 2030 greenhouse gas reduction goal can be achieved without inflicting unanticipated and undue harm on New York consumers, and the concrete analysis in the 2025 Draft Energy Plan dispels any uncertainty on the topic: New Yorkers will face alarming financial consequences if speed is given preference over sustainability.

Conclusion

It is impossible to ignore that multiple independent analyses, audits, litigation findings, and party filings in DPS proceedings document that the Climate Act transition will exacerbate energy affordability issues at a time when more than a million New York households are already in arrears on their energy bill. Unfortunately, the Hochul Administration and Legislature have not adopted clear affordability metrics, a transparent tracking system, or mandatory corrective actions when affordability thresholds are exceeded. Of course, these are bright line accountability metrics, and no political supporter of the Climate Act wants to admit their role in the New York affordability crisis.