The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (Climate Act) has a legal mandate for New York State greenhouse gas emissions to meet the ambitious net-zero goal by 2050. In order to implement the changes needed additional legislation is needed. Environmental advocates are pushing Renewable Heat Now bills including the All-Electric Building Act. This post puts that legislation into the context of the current electricity reliability crisis facing New Yorkers.

Everyone wants to do right by the environment to the extent that they can afford to and not be unduly burdened by the effects of environmental policies. I have written extensively on implementation of New York’s response to climate change risk because I believe the ambitions for a zero-emissions economy embodied in the Climate Act outstrip available renewable technology such that it will adversely affect reliability, impact affordability, risk safety, affect lifestyles, and will have worse impacts on the environment than the purported effects of climate change in New York. New York’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions are less than one half one percent of global emissions and since 1990 global GHG emissions have increased by more than one half a percent per year. Moreover, the reductions cannot measurably affect global warming when implemented. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Climate Act Background

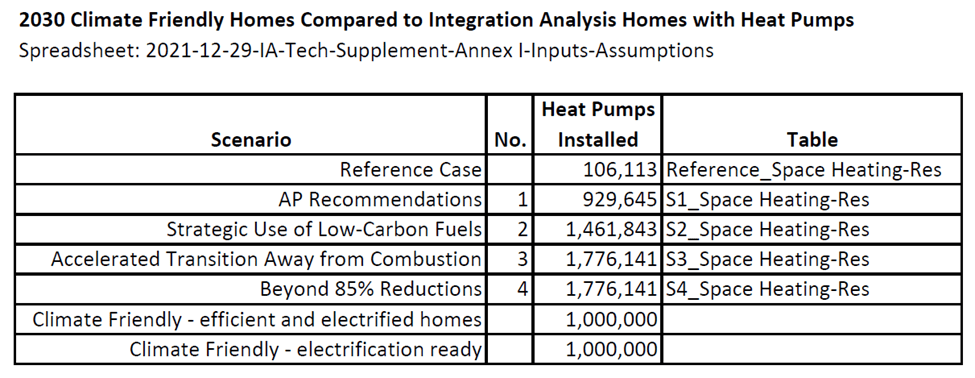

The Climate Act establishes a “Net Zero” target by 2050. The Climate Action Council is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that will “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda”. They were assisted by Advisory Panels who developed and presented strategies to the meet the goals to the Council. Those strategies were used to develop the integration analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants that quantified the impact of the strategies. That analysis was used to develop the Draft Scoping Plan that was released for public comment on December 30, 2021.

I previously described two bills that address the building sector components that need to be changed for the net-zero transition. According to the Advanced Code Act: “Buildings are the single largest user of energy in the State of New York, accounting for almost 60% of all energy consumed by end-use in the State.” Revisions to building codes will be “directly impacting a building’s energy load and carbon footprint”. The Gas Ban notes that the Climate Act “requires greenhouse gas emission reductions from all sectors, which will entail, among other things, converting buildings throughout the state from heating and cooking with combustible fuels to heating and cooking with non-emitting sources such as energy-efficient air, ground, and water sourced electric heat pumps which also provide cooling, and electric and induction stoves”. I understand that the Advanced Code Act has already passed.

All Electric Building Act

I described the public hearing for this legislation that establishes the All-Electric Building Act. As has been the case with other legislation the bill assumes that there are no technology limitations and that all new buildings can be built without fossil fuel infrastructure without any issues.

The proposed legislation revises the state energy conservation construction code to “prohibit infrastructure, building systems, or equipment used for the combustion of fossil fuels in new construction statewide no later than December 31, 2023 if the building is less than seven stories and July 1, 2027 if the building is seven stories or more”. It allows the building code council to exempt systems for emergency back-up power, or buildings specifically designated for occupancy by a “commercial food establishment, laboratory, laundromat, hospital, or crematorium, but in doing so shall seek to minimize emissions and maximize health, safety, and fire-protection.” However, it limits the areas where the combustion of fossil fuels is allowed and the building must be designed as all-electric ready.

The legislation includes a provision for affordability. It requires state agencies to identify policies to ensure affordable housing and affordable electricity (meaning that electricity costs no more than 6% of a residential customer’s income) for all-electric buildings by February 1st, 2023. Note that I have been unable to determine the current affordability status of New York.

Affordability

Energy affordability, in general, and electricity affordability, in particular, should be a major concern. There is no question that there is a home energy crisis:

According to WE ACT for Environmental Justice, an organization whose mission is to combat environmental racism and build healthy communities for people of color, 13 percent of all residential households—about 1,137,000 in total—are 60 days in arrears on their utility bills, with an average of $1,427.71 in debt. The debt level is even higher for Con Ed customers, averaging about $2,085 per residential household/customer.

More than 471,629 disconnection notices were sent out in April 2022 for residential customers across New York State, with Orange and Rockland counties leading the way, with 79 shutoffs that month. For commercial customers, there were more than 77,651 disconnection notices overall, with almost 2,544 already carried out. National Grid (KEDLI) had the highest number of service terminations, 882, followed by Con Edison at 831 terminations and National Grid (KEDNY) at 310. Residential terminations in March were at 131 and commercial terminations stood at 1,688.

The proposed legislation addresses affordability but puts the cart before the horse by evaluating electricity affordability after the bill is enacted:

§ 11-111. Additional reporting. On or before February first, two thousand twenty-three, the department of public service, the division of housing and community renewal, the department of state, and the New York state energy research and development authority shall report jointly to the governor, the temporary president of the senate, the minority leader of the senate, the speaker of the assembly, and the minority leader of the assembly, regarding what changes to electric rate designs, new or existing subsidy programs, policies, or laws are necessary to ensure that subdivisions six and seven of section 11-104 of this article do not diminish the production of affordable housing or the affordability of electricity for customers in all-electric buildings. For the purpose of this subdivision, “affordability of electricity” shall mean that electricity does not cost more than six percent of a residential customer’s income.

In 2016, New York State set a target that low-income New Yorkers should pay no more than 6% of their income toward energy bills and I applaud its inclusion in this legislation. However, I have not been able to find out how New York State stands relative to this target. I did find an analysis for New York City that showed that over 460,000 low-income families in New York City are paying over 6% of their pre-tax income toward their energy bills. That works out to 14.6% of the households.

All Electric Building Act Costs

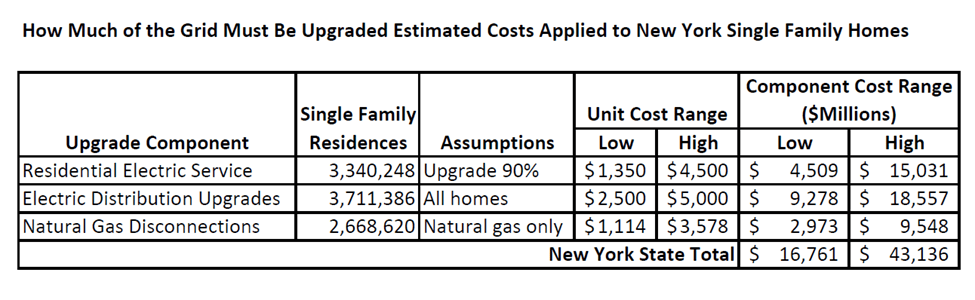

I have yet to see an evaluation of the potential costs of this legislation. The Integration Analysis spreadsheets that support the Draft Scoping Plan include a table with device costs. In order to ensure that heat pumps work at all times in New York’s winters upgrades to the building shell (insulation, infiltration and windows) are needed. According to device cost table an air source heat pump runs $14,678 and a deep shell upgrade of $45,136 totaling $59,814 or a ground source heat pump ($34,082) and a basic shell upgrade ($6,409) totaling $40,491 for single family homes. This legislation would mandate adding those costs above the cost of an efficient furnace or boiler ranging from $3,085 to $8,975. Obviously, those added costs are going to add to the affordability burden for New Yorkers.

Conclusion

The bill requires a study after the law becomes effective to ensure it does not “diminish the production of affordable housing or the affordability of electricity for customers in all-electric buildings”. That is an example of the cart before the horse mindset of this legislation and the Climate Act itself. This bill should be amended to include a specific affordability target and only proceed as long as the metric is achieved. I think that there should be a state-wide goal for the percentage of customers that don’t meet the 6% target and the State should make the current value readily available. Without that information it is inappropriate to implement this legislation.

By any measure New York’s complete elimination of GHG emissions is so small that there will not be any effect on the state’s climate and global climate change impacts to New York. New York’s emissions are only 0.45% of global emissions. I have shown that global emissions have increased more than New York’s total share of global emissions since 1995. In other words, whatever New York does to reduce emissions will be supplanted by global emissions increases in a year. Against that backdrop it is not clear why any increase in New York energy costs from any renewable heat legislation should be considered until the electricity energy crisis is resolved.