Since November 2023 Kris Martin has been producing great articles at the Solar Divide blog documenting issues associated with the buildout of solar in New York associated with the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act). I highly recommend her website archive as a resource about issues associated with the irresponsible buildout of solar in New York and signing up alerts for her articles by subscribing to her Substack.

Background

Kris Martin is a retired software engineer in Western NY who writes about solar and wind buildout in rural communities. At first glance her background does not appear to be applicable to renewable topics but it is my experience that 90% of the effort writing about renewable deployment in New York is tracking down state documentation. As a software engineer, she has temperament to sift through reams of clutter to find the nuggets of relevant information necessary to show what is happening with complicated topics.

Overview

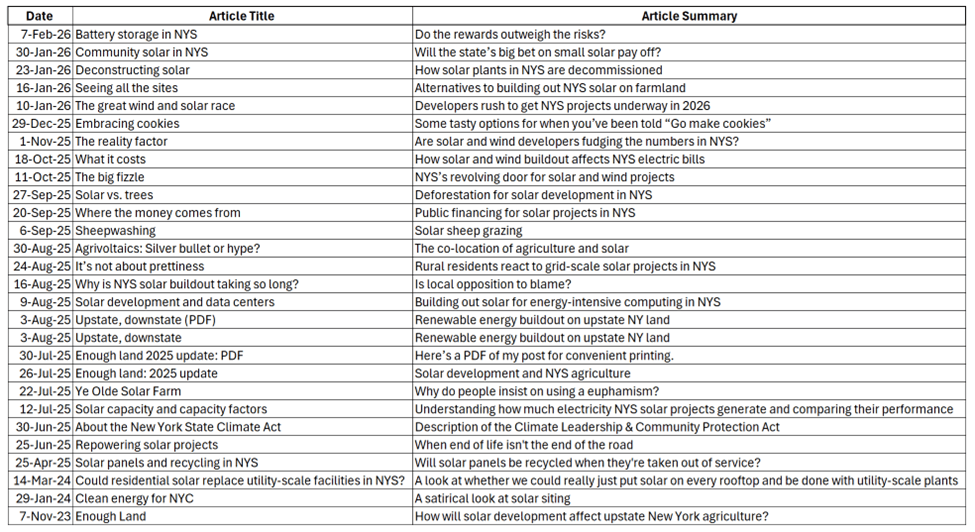

Martin’s archive includes 28 articles (Table 1). Most of the articles were published in the past year. If you have a particular question about solar issues, I think just scanning through this list or the website archive itself will enable you to find information about most of the solar issues confronting New York. Also note that many of her articles also provide a link to a pdf copy for download.

Table 1: Archive List of Solar Divide Articles

In the following sections I recommend specific articles covering several topics.

Costs

Kris Martin has done several articles about the costs of solar.

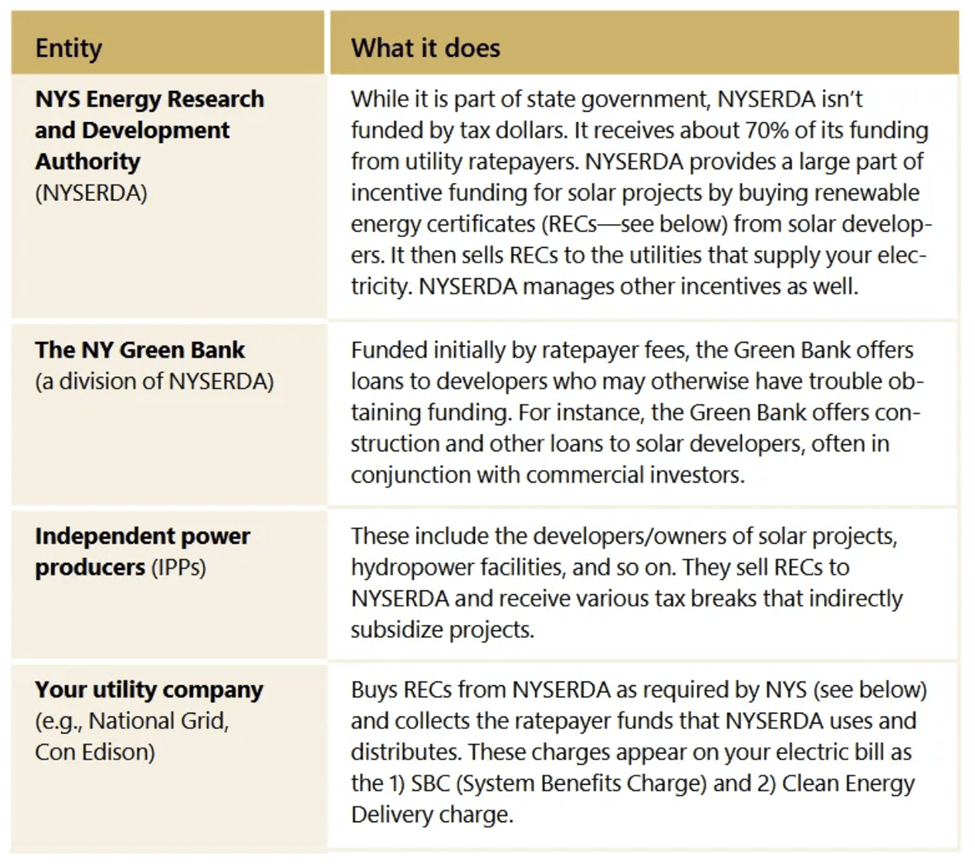

One of my favorite articles explained solar subsidies because I wanted to know how this works but understood that unpacking how it works would be a long and frustrating effort. I am indebted to her for figuring it out and then writing a clear and concise description. She used a table to describe the entities playing the games in New York.

The article went on to describe the acronyms and why they matter, where developers can get loans from the state, how the Federal tax credits work, and forms of tax relief. Then summed up some of the major public funding sources for solar developers and who ultimately pays for each one on the following table.

She concludes:

Is NYS building out wind and solar on the backs of those who can least afford it? This question should concern those seeking to protect vulnerable populations from predatory corporate behaviors. After all, solar developers aren’t trying to save us from climate change—they’re profiting from it.

The post What it costs was another laudable cost-related effort that dug through many documents to uncover numbers that gubernatorial candidate Hochul does not want you to know. This post looked at three issues:

- How much more renewable capacity we’ll need in 2040

- What it all costs: now and in the future

- What happens if we fail to meet the requirements of the Climate Act

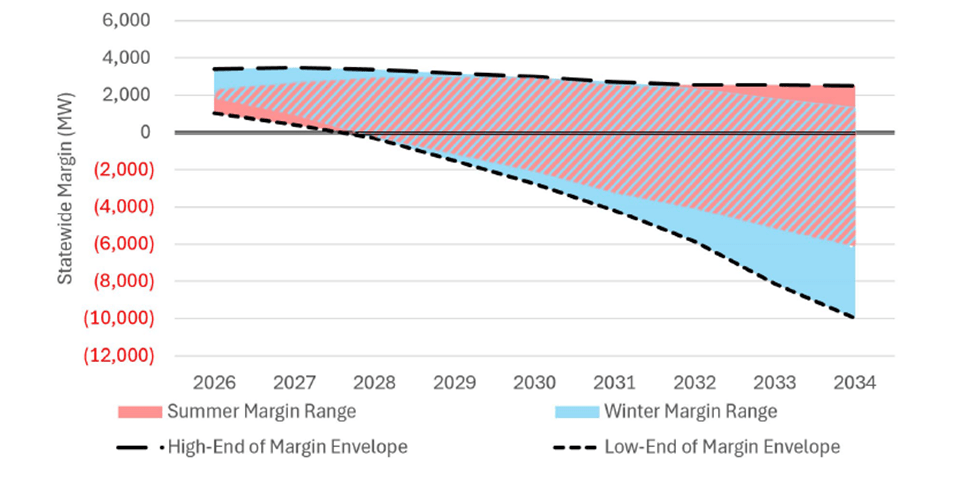

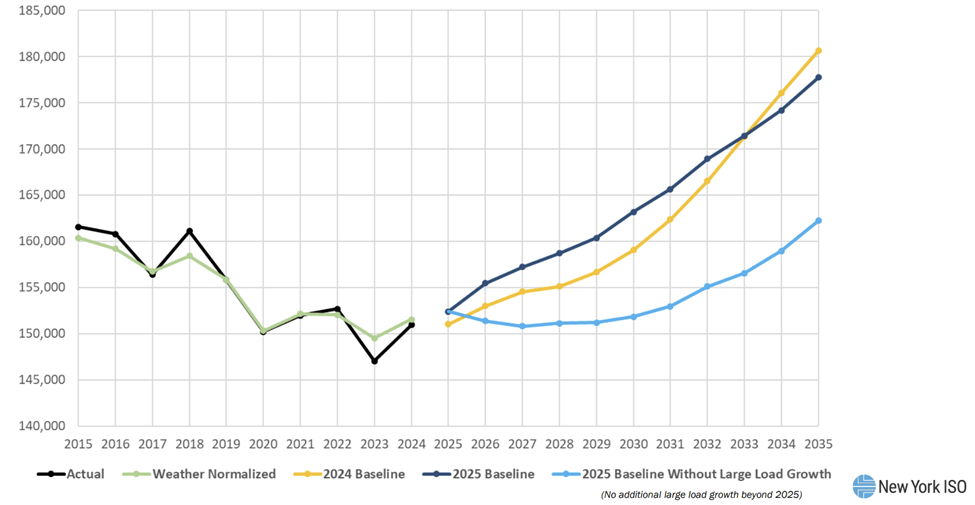

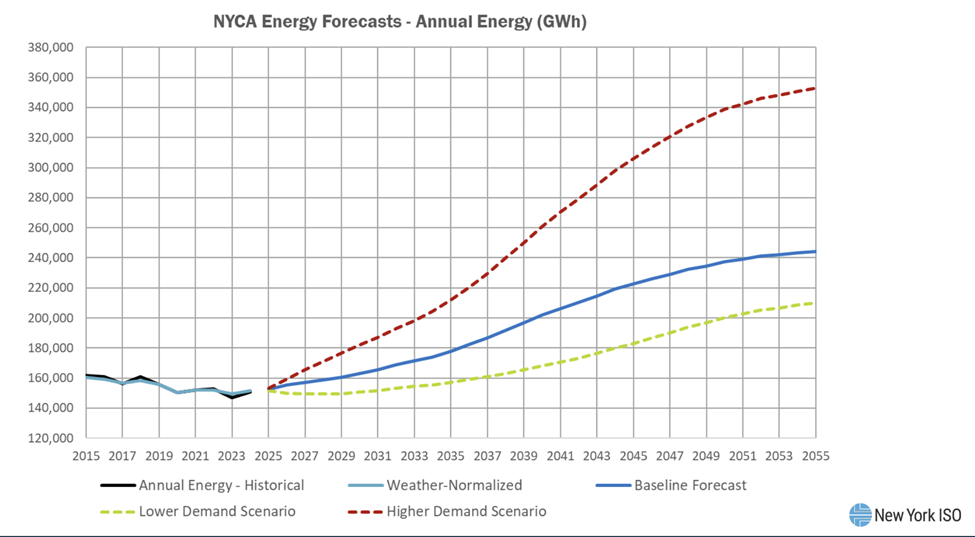

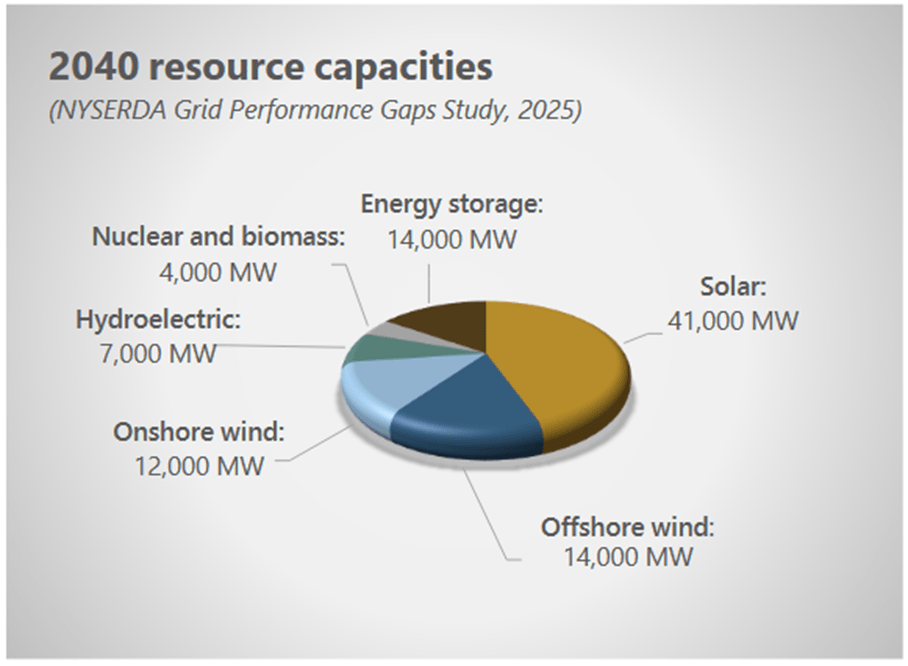

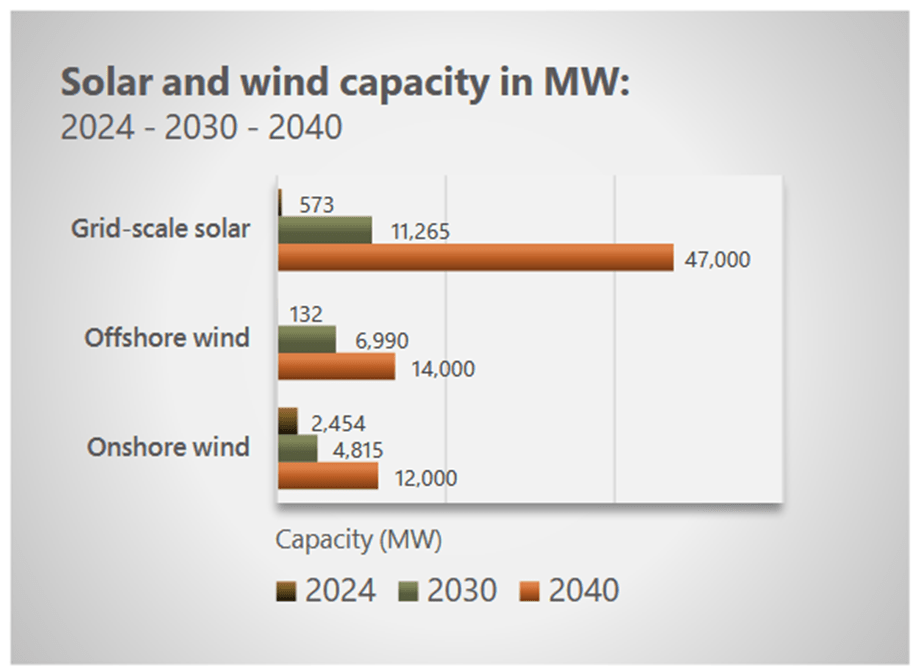

One of the best characteristics of her articles is her use of graphics to explain issues. The following figure shows how much renewable capacity is needed by 2040 based on one estimate from the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO).

Her next graphic shows where we stand today relative to the expected need.

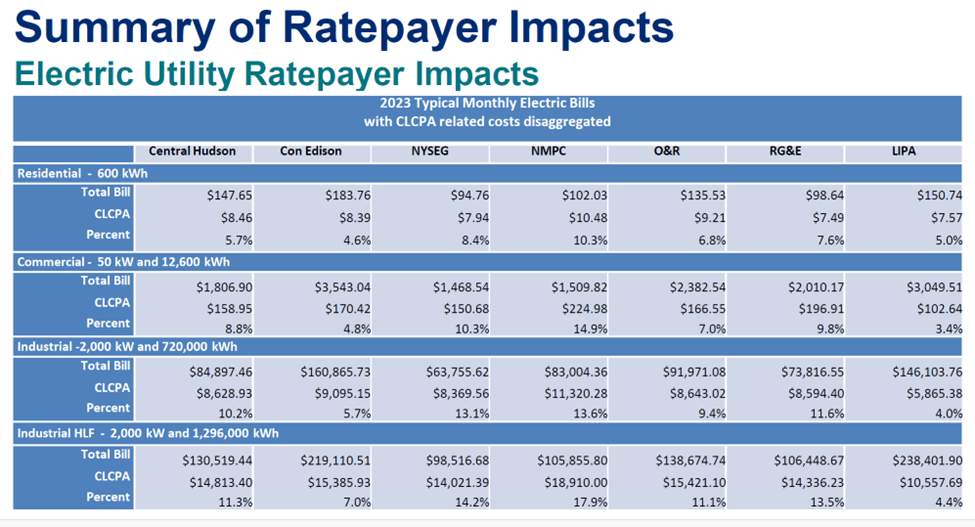

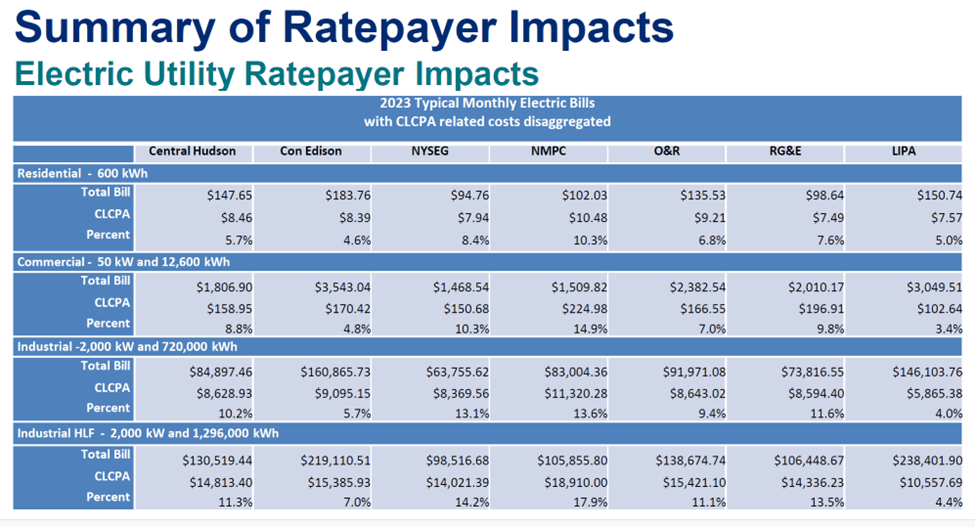

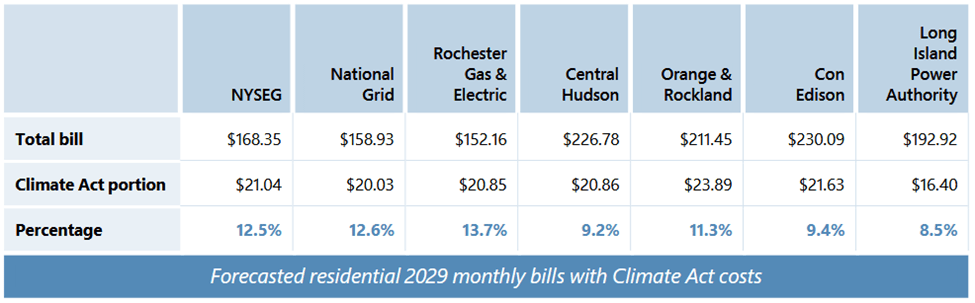

This post has another example of analysis she did that I was planning to do but never got around to doing. She described the expected costs in the DPS informational report and why they came up with suspiciously low numbers.

Her analysis found that these estimates for future costs don’t include all the Renewable Energy Credits (REC) and OREC (offshore wind REC) costs that would be required to reach Climate Act targets—or even what they might realistically expect to complete.

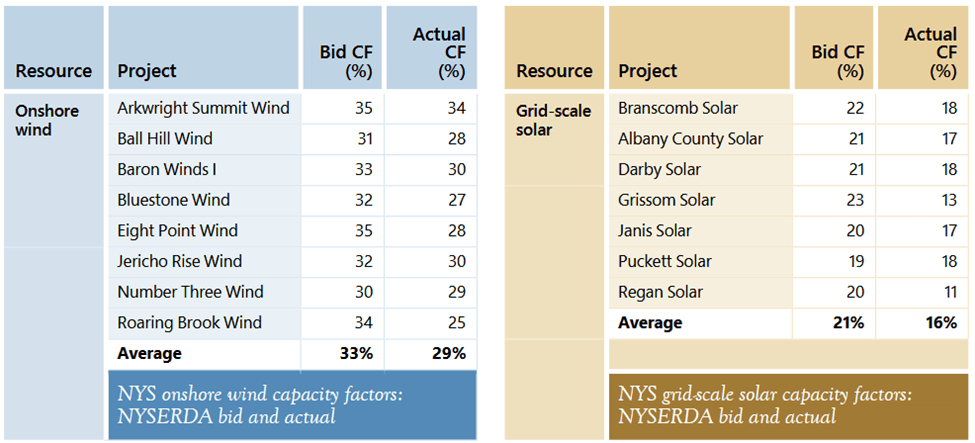

In another post discussing solar costs she discussed the possibility that the developers are fudging the numbers that project whether a solar project will ever generate enough energy to earn its keep. While she tries to minimize using numbers for her articles this is one instance where the capacity factor number must be considered. She defined capacity factor as “the percentage of the time it generated electricity at full capacity, compared with how much it could produce if it operated at full capacity 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.” That is not exactly correct. It is the actual electricity produced at any capacity compared to the full capacity, but it shouldn’t make a difference because she relied on published capacity factors and did not calculate them herself.

She found that the expected energy output in the bids and the observed output were significantly less. This has significant ramifications. NYSERDA estimates of the renewable capacity needed are too low because they assumed unrealistic capacity factors. The developer projections of expected energy projection determine if the project will be viable. If those estimates are wrong, I am positive that they will go back to NYSERDA and ask for more money. NYSERDA cannot afford for them to stop operating so they will pay up and consumers will end up footing the bill.

Land Use

One of my issues associated with solar deployment is the fact that New York State does not have a requirement for solar developers to minimize the use of prime farmland. I highly recommend Martin’s look at the land requirements for solar buildout in upstate NY between now and 2050 as described in this post. The original analysis was described in a white paper called Enough Land that was documented in her first post. In August 2025 she updated the white paper.

Her analysis documents the fact that NYS experienced a 5.3% loss in farmland and 5% loss in cropland between 2017 and 2022. She points out that this loss is before much utility scale solar was deployed. She estimates how much solar capacity will need to be deployed to meet Climate Act goals and concludes:

More than a quarter of the state’s present farmland and a third of its cropland may be at risk from combined solar and non-solar development by 2050. These numbers mean we must look hard at all proposals that remove farmland from production.

As a born and raised Upstate New Yorker I have always resented the restrictions on land use imposed by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYC DEP) through its Watershed Rules and Regulations. Martin describes the conflict between Upstate NY and the downstate region over the renewable energy buildout. She explains that folks like me have noted that the upstate/downstate relationship reflects a pattern of neocolonialism in which NYC has dictated upstate land use. Historically, when NYC needed upstate land resources, upstate residents have had no say in the decisions. She notes:

The goal of procuring clean energy for NYC has become a state priority, which has created an alliance between the city, state government, and renewable energy corporations. Consequently, today NYC is effectively establishing what amounts to an energy plantation on upstate land with the full support of state government. Individual property owners may choose whether to lease or sell their land for conversion to grid-scale renewable energy facilities, but communities and adjacent landowners have no decision-making role in siting them.

Two other articles also address land use problems. Solar vs. trees addresses the issues associated with solar development in forests. The article Seeing all the Sites discusses the alternatives to building out solar on farmland. This is a good example of her in-depth analysis because she evaluates the arguments of responsible solar siting advocates and concludes that there simply is not enough “responsible” solar siting area to meet the solar capacity projections.

Retirements

Martin addressed the fate of the solar panels when they stop operating because of old age, damage, or owner insolvency. She notes that the good news is that most facilities have decommissioning plans but that means the bad news s there are facilities that do not. In another post she explained the other alternative that when a facility is past its prime that it will be re-powered. She also prepared a two page summary addressing recycling of solar panels.

These posts define another example of what I have found regarding every Climate Act issue. The reality is that every problem is more complicated, resolution more uncertain, and the costs are higher than the state has planned for or admitted. These articles are great examples illustrating the problems with what will happen when these facilities stop operating. She concluded:

NYS urgently needs a statewide requirement that all solar installations—both residential and utility-scale—must have decommissioning plans. Decommissioning funds must be provided for utility-scale projects of all sizes. ORES should respect the host community’s efforts to protect itself and not waive local laws that are more protective than the state requires. Given that communities are often selected in part because they are economically disadvantaged, they deserve all the protection the state can give them.

Overviews

Finally, because she has a knack for explaining complicated topics simply, I want to recommend the following overview articles that describe the Climate Act itself and two components in the implementation plans.

Martin’s description of community solar is very good. She describes these facilities as follows:

Most community solar in NYS consists of 1-5 MWac utility-scale solar projects with multiple subscribers: residential, commercial, and other electricity consumers. Most sign up to get discounts of up to 10% on their electric bills. Unlike with residential solar installations, customers typically don’t own or lease the solar panels directly. Usually, these small plants are owned by solar developers, who receive various incentives and assistance to build and operate those facilities. One of the state’s goals is to sign up customers who can’t install residential solar because they can’t manage the up-front cost, don’t have an appropriate site, or don’t own their homes. A certain percentage of a project’s subscribers must be residential users, but commercial users may also take advantage of the discounts offered.

The article describes the characteristics, locations, battles between developers and local jurisdictions about these facilities, costs, and project performance. She explains that “By providing generous assistance and favorable, predictable conditions for developing and selling electricity from community solar, the state has made itself an appealing choice for companies wanting to build small solar projects.” She concludes:

As seems typical with state energy transition goals, we’ve invested an awful lot of money without demanding much accountability. It’s possible that community solar is contributing to resilience and reducing bills, but we don’t actually know it.

NYS’s 2030 goal of 10,000 MWdc of distributed solar may be one of the few we will meet on time. The state deserves bragging rights over building a large amount of community solar in a short time. It has created a favorable environment for developers, in which they can earn steady revenue despite mediocre performance. But buildout has sometimes taken place at the expense of rural communities, who may lack the knowledge and resources to evaluate these projects effectively and ensure compliance during and after construction.

Martin recently published an overview of battery energy storage systems (BESS) in New York. Again, it is a well-researched, readable, and comprehensive summary of one aspect of the Climate Act. She concludes:

Advocates of BESS insist that “the latest” li-ion technology is safe, that incidents are extremely rare, and communities are being misled by activists who find inaccurate information on the Internet. Most of what I have presented here comes from industry, government, news, and academic sources. While we would all like to say that the chance of a BESS fire occurring is so remote that it can be dismissed; five fires in NYS in the last three years suggest otherwise.

While proponents assert that utility-scale BESS deployments are crucial for NYS’s energy goals, the economic, environmental, and safety risks remain profound. The high costs of facilities, questions about adequate emergency response, environmental threats, and real-world incidents highlight the need for a cautious, community-first approach to battery storage. Policymakers should address these challenges before endorsing a large-scale BESS rollout across NYS.

Conclusion

I have a solar isses page that discusses many of the same issues covered by Marting, but her work should be a primary resource for anyone concerned about New York solar siting issues. Her website archive is a great resource about issues associated with the irresponsible buildout of solar in New York. If you are interested in any of these topics then I suggest signing up for alerts her articles are published by subscribing to her Substack.