The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (Climate Act) establishes a “Net Zero” target by 2050. The Draft Scoping Plan defines how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda”. However, there is increasing evidence that this dream is unrealistic. This post describes an article by Gail Tverberg at Our Finite World that explains that “It is becoming clear that modelers who encouraged the view that a smooth transition to wind, solar, and hydroelectric is possible have missed some important points”.

I have written extensively on implementation of the Climate Act because I believe the ambitions for a zero-emissions economy outstrip available technology such that it will adversely affect reliability and affordability, risk safety, affect lifestyles, will have worse impacts on the environment than the purported effects of climate change in New York, and cannot measurably affect global warming when implemented. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

The Climate Action Council is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that will “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda”. The Climate Act requires the Climate Action Council to “[e]valuate, using the best available economic models, emission estimation techniques and other scientific methods, the total potential costs and potential economic and non-economic benefits of the plan for reducing greenhouse gases, and make such evaluation publicly available” in the Scoping Plan. Starting in the fall of 2020 seven advisory panels developed recommended strategies to meet the targets that were presented to the Climate Action Council in the spring of 2021. Those recommendations were translated into specific policy options in an integration analysis by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants. The integration analysis was used to develop the Draft Scoping Plan that was released for public comment on December 30, 2021.

The Climate Act authors presumed that implementing the net-zero target was simply a matter of political will. The Draft Scoping Plan does not incorporate a feasibility analysis to determine if this transition can occur without impacting reliability and affordability. This post describes an independent analysis of the feasibility of any similar transition.

Gail Tverberg is an actuary interested in finite world issues – oil depletion, natural gas depletion, water shortages, and climate change. She argues that oil limits look very different from what most expect, with high prices leading to recession, and low prices leading to financial problems for oil producers and for oil exporting countries. We are really dealing with a physics problem that affects many parts of the economy at once, including wages and the financial system. She tries to look at the overall problem. I have found her work to be insightful and compelling. However, I think she downplays the potential for human ingenuity to resolve energy depletion problems.

Discussion

Tverberg describes six different reasons why she thinks the net-zero transition is not going as advocates claimed that it would. I summarize her points below but encourage readers to go to her article for a more complete description. Where appropriate I comment on the applicability to New York’s Climate Act.

Her first point is that variability is a major problem. She explains that the belief was that with the use of enough intermittent renewables or by using long transmission lines it would enable enough transfer of electricity between locations to largely offset variability. However, in the third quarter of 2021, weak winds were a significant contributor to a European power crunch. Europe’s largest wind producers (Britain, Germany and France) produced only 14% of installed capacity during this period, compared with an average of 20% to 26% in previous years. Because no one had planned for this kind of three-month shortfall prices skyrocketed.

Secondly, she states:

Adequate storage for electricity is not feasible in any reasonable timeframe. This means that if cold countries are not to “freeze in the dark” during winter, fossil fuel backup is likely to be needed for many years in the future.

One workaround for electricity variability is storage. A recent Reuters’ article is titled, Weak winds worsened Europe’s power crunch; utilities need better storage. The article quotes Matthew Jones, lead analyst for EU Power, as saying that low or zero-emissions backup-capacity is “still more than a decade away from being available at scale.” Thus, having huge batteries or hydrogen storage at the scale needed for months of storage is not something that can reasonably be created now or in the next several years.

This is of particular concern for New York’s implementation of the Climate Act. In particular, the fossil fuel phaseout on a date-certain schedule is going to run up against the timing of the “still more than a decade away from being available at scale” outlook. In my opinion, the outlook she quoted is optimistic for the availability of the technology. Permitting, acquisition and construction for new technology is almost certain to take longer than proposed by the New York Draft Scoping Plan.

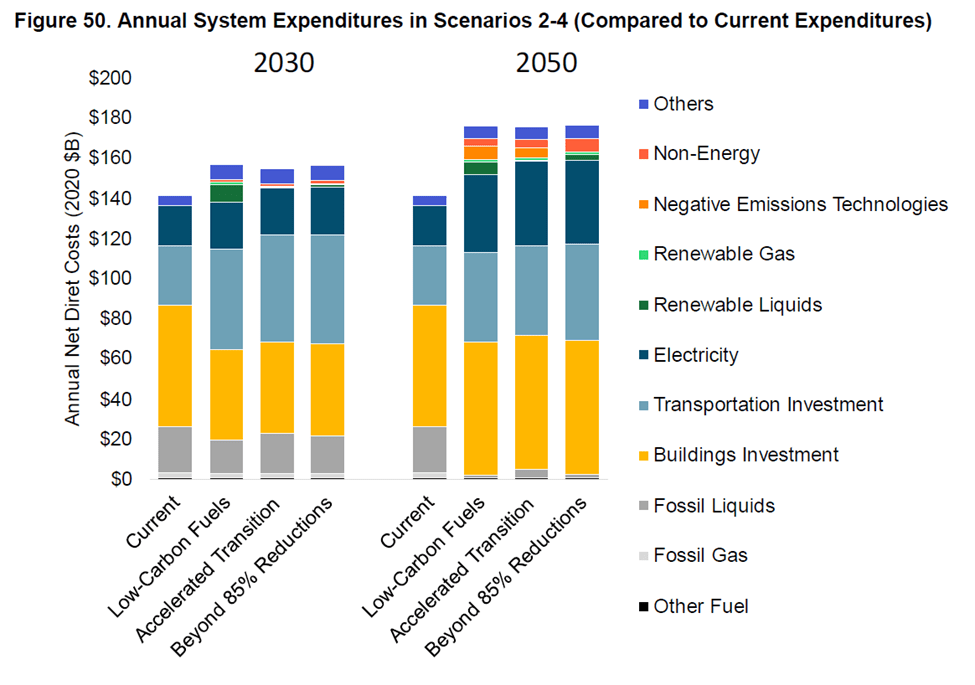

She goes on to point out that capacity for multiple months of electricity storage is needed. “Such storage would require an amazingly large quantity of materials to produce.” She goes on to point out that: “Needless to say, if such storage were included, the cost of the overall electrical system would be substantially higher than we have been led to believe.” I have found no indication whatsoever that these costs are adequately addressed in the Draft Scoping Plan.

Her third point is that despite many years of subsidies and mandates, today’s green electricity is only a tiny fraction of what is needed to keep our current economy operating. Advocates have simply underestimated how difficult it would be to ramp up green electricity. While New York may be ahead of many jurisdictions in its proportion of renewable energy that is primarily due to the hydro power resources at Niagara Falls and the Saint Lawrence River. Any addition renewable development is going to be much more difficult to ramp up.

Tverberg s fourth point is renewables comprised a relatively small share of percentage of electricity in 2020. She explains why this is important:

Wind and solar don’t replace “dispatchable” generation; they provide some temporary electricity supply, but they tend to make the overall electrical system more difficult to operate because of the variability introduced. Renewables are available only part of the time, so other types of electricity suppliers are still needed when supply temporarily isn’t available. In a sense, all they are replacing is part of the fuel required to make electricity. The fixed costs of backup electricity providers are not adequately compensated, nor are the costs of the added complexity introduced into the system.

If analysts give wind and solar full credit for replacing electricity, as BP does, then, on a world basis, wind electricity replaced 6% of total electricity consumed in 2020. Solar electricity replaced 3% of total electricity provided, and hydro replaced 16% of world electricity. On a combined basis, wind and solar provided 9% of world electricity. With hydro included as well, these renewables amounted to 25% of world electricity supply in 2020.

Her final two points paint a very pessimistic view of the future of the world economy. Both are based on the idea that resource availability will eventually lead to shortages because there is no way the system can ramp up needed production in a huge number of areas at once so supply lines will break. She argues that this means “Recession is likely to set in.” This is based on the following:

The way in which the economy would run short of investment materials was simulated in the 1972 book, The Limits to Growth, by Donella Meadows and others. The book gave the results of a number of simulations regarding how the world economy would behave in the future. Virtually all of the simulations indicated that eventually the economy would reach limits to growth. A major problem was that too large a share of the output of the economy was needed for reinvestment, leaving too little for other uses. In the base model, such limits to growth came about now, in the middle of the first half of the 21st century. The economy would stop growing and gradually start to collapse.

She goes on to argue that there are signs that this is happening now.

I don’t want to debate this worldview so I will just point out that The Limits to Growth states: “If all the policies instituted in 1975 in the previous figure are delayed until the year 2000, the equilibrium state is no longer sustainable. Population and industrial capital reach levels high enough to create food and resource shortages before the year 2000.” This did not happen and I am uncomfortable accepting this belief completely. If Chicken Little said “the sky is falling – this time for sure” I don’t think I would have more confidence in the projection. As a result, I am more inclined to support the analysis of Robert Bradley who disagrees with the Limits to Growth outlook.

One of the arguments for switching to renewable energy is that fossil fuels will eventually run out and we need to have a sustainable source of energy in place. However, Tverberg’ s analysis explains that the same resource availability concerns are relevant for the materials needed to produce electricity from wind and solar facilities. In particular, production of the rare earth elements needed for the magnets and batteries that are critical to wind and solar deployment may be less sustainable than continued development of fossil fuels. Although these elements aren’t all that rare, they are assigned that descriptor because economically feasible deposits are difficult to come by – when the elements are discovered in high enough concentrations to be mined, they are found together in complex mixtures that require substantial effort to further purify. For instance, to manufacture each electric auto battery 25,000 pounds of brine for the lithium, 30,000 pounds of ore for the cobalt, 5,000 pounds of ore for the nickel, and 25,000 pounds of ore for copper must be processed. All told, you dig up 500,000 pounds of the earth’s crust for just – one – electric vehicle battery. In my opinion, the combination of few locations where the elements are in high enough concentrations to economically process, the mass of ore needed to extract the elements and the environmental effects of the purification process combine to make their resource availability concern larger than fossil fuel availability.

Conclusion

I think that the points she makes about renewable variability, energy storage, and the lack of substantial progress implementing renewable energy despite many years of subsidies are important. I don not believe that the Draft Scoping Plan adequately addresses those issues.

Although I disagree with some of the issues raised by Tverberg, I find her conclusion that “Modelers and leaders everywhere have had a basic misunderstanding of how the economy operates and what limits we are up against” compelling. This is especially important in the context that these modelers and leaders want to completely change the current energy system. She argues that:

The real problem is that diminishing returns leads to huge investment needs in many areas simultaneously. One or two of these investment needs could perhaps be handled, but not all of them, all at once.

Despite the lack of historical evidence that resource availability problems cannot be resolved by human ingenuity, I think it is still appropriate to consider those problems. In the context of a green energy transition, the question becomes which is the more feasible approach for the huge investments needed for global energy? In my opinion, I think that investments in fossil fuel infrastructure are the better choice because of the rare earth element sustainability issues described here. That is an ironic conclusion given that one of the reasons that Climate Act proponents want to transition away from fossil fuels is because of their belief that fossil fuels will run out soon.