On September 9, 2024 the Hochul Administration initiated the development of the State Energy Plan announcing the release of a draft scope of the plan. On November 15 New Yorkers for Clean Power (NYCP) sponsored a webinar titled “Get Charged Up for the New York Energy Plan” that was intended to brief their supporters about the Energy Plan. This article will be the first of two posts addressing this webinar. I have a tendency to write comprehensive posts that are too long for my readers so I am going to break this story up.

I am convinced that implementation of the New York Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) net-zero mandates will do more harm than good if the electric system transition relies on wind, solar, and energy storage. I have followed the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 470 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. It includes an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% GHG reduction by 2030. Two targets address the electric sector: 70% of the electricity must come from renewable energy by 2030 and all electricity must be generated by “zero-emissions” resources by 2040. The Climate Action Council (CAC) was responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlined how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantified the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to develop the Draft Scoping Plan outline of strategies. After a year-long review, the Scoping Plan was finalized at the end of 2022. Since then, the State has been trying to implement the Scoping Plan recommendations through regulations, proceedings, and legislation.

Although related, the Energy Plan should not be confused with the Scoping Plan. Every several years the New York Energy Planning Board is required to update its overall energy plan for the state. The process begins with an initial document that identifies a “scope” of work–meaning the set of things to be evaluated in the plan with a defined planning horizon of 2040. This makes the Climate Act’s 2040 goal of carbon-free electricity particularly relevant. Unlike the 70% renewable goal which only applies in 2030, the 2040 goal does not mandate an arbitrary quota of “renewables”. Instead, it simply mandates carbon-free electricity, which can include nuclear power.

Key Action Items from the Webinar

The description of the New Yorkers for Clean Power webinar titled “Get Charged Up for the New York Energy Plan” stated:

Thank you for joining us for the “Get Charged Up for the New York State Energy Plan” Teach-In on November 15th. We are electrified by the demonstrated interest and information shared to support New York’s climate goals through the development of an ambitious and equitable State Energy Plan. To recap, our featured speakers were:

- Janet Joseph, Principal, JLJ Sustainability Solutions (Former VP of Strategy and Market Development, NYSERDA

- Dr. Robert Howarth, Member, New York’s Climate Action Council, and David R. Atkinson Professor of Ecology and Environmental Biology at Cornell University

- Christopher Casey, Utility Regulatory Director for New York Climate and Energy, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)

We’re excited to share the recording and slideshow from the event: Here is the recording of the event and check out the Presenters’ slides here.

Key Takeaways from the Event

- Energy Plan is foundational to achieving New York’s climate and energy goals, aligning policies with the CLCPA.

- Engagement from advocates, community members and developers is critical for ensuring equitable and actionable outcomes

- Challenges like building decarbonization and system reliability require innovative solutions and statutory changes.

I am going to address the presentations of Janet Joseph and Robert Howarth in a later post. I disagree with their comments that downplay my concern that transitioning the New York electric grid to one that relies primarily on wind, solar, and energy storage will adversely affect reliability and affordability. This post is going to describe Dr. Howarth’s response to my specific question about the need for a feasibility analysis.

Feasibility Analysis Background

Dr. Howarth is venerated by New York environmental advocates but I think their faith is misplaced. His Introduction at the webinar extolled his role in vilifying methane’s alleged importance as a greenhouse gas. I think that obsession is irrational. The hostess also lauded his work supporting a Biden Administration pause on applications for LNG export terminals. However his analysis was “riddled with errors” and he eventually retracted some of the more extreme claims that received media attention.

Howarth claims that he played a key role in the drafting of the Climate Act and his statement at the meeting where the Scopng Plan was approved claims that no new technology is needed:

I further wish to acknowledge the incredible role that Prof. Mark Jacobson of Stanford has played in moving the entire world towards a carbon-free future, including New York State. A decade ago, Jacobson, I and others laid out a specific plan for New York (Jacobson et al. 2013). In that peer-reviewed analysis, we demonstrated that our State could rapidly move away from fossil fuels and instead be fueled completely by the power of the wind, the sun, and hydro. We further demonstrated that it could be done completely with technologies available at that time (a decade ago), that it could be cost effective, that it would be hugely beneficial for public health and energy security, and that it would stimulate a large increase in well-paying jobs. I have seen nothing in the past decade that would dissuade me from pushing for the same path forward. The economic arguments have only grown stronger, the climate crisis more severe. The fundamental arguments remain the same.

As I will show in this article, I think his claim that the transition can be implemented using wind, sun, and hydro using existing technologies is wrong.

Do We Need a Feasibility Analysis?

I thought it would be appropriate to give Howarth the opportunity to recant his feasibility claim so I submitted the following question:

On November 4, 2024, the New York Department of Public Service (DPS) staff proposal concerning definitions for key terms notes that “Pursuing the 2040 target will require the deployment of novel technologies and their integration into a changing grid”. Should there be a feasibility analysis in the energy plan to address their concern about the new technologies?

In his response, Howarth admitted that he was not familiar with the particular reference to the DPS proceeding that is implanting the Climate Act mandates. Then he answered (my lightly edited transcription of his responses):

I can give you the perspective of three years of discussion on the CAC. That it is we firmly stated that the goals can be met with existing technologies. We don’t need novel technologies.

One of my unresolved questions relative to Howarth’s position and the Scoping Plan is that he voted to support the Scoping Plan. However, the Scoping Plan explicitly contradicts his statement that technologies available in 2013 were sufficient for the transition away from fossil fuels. In particular, the Final Scoping Plan Appendix G, Section I page 49 states (my highlight included):

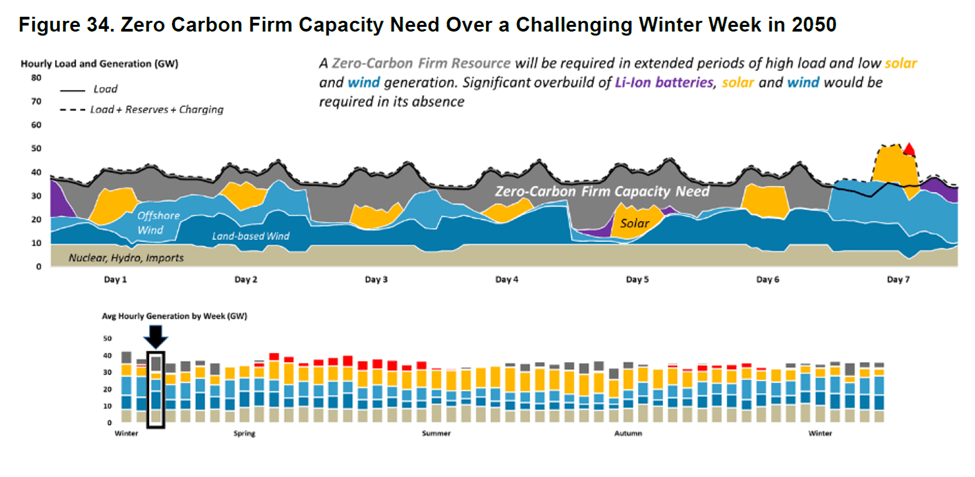

During a week with persistently low solar and wind generation, additional firm zero-carbon resources, beyond the contributions of existing nuclear, imports, and hydro, are needed to avoid a significant shortfall; Figure 34 demonstrates the system needs during this type of week. During the first day of this week, most of the short-duration battery storage is quickly depleted, and there are still several days in which wind and solar are not sufficient to meet demand. A zero-carbon firm resource becomes essential to maintaining system reliability during such instances. In the modeled pathways, the need for a firm zero-carbon resource is met with hydrogen-based resources; ultimately, this system need could be met by a number of different emerging technologies.

In addition to the Scoping Plan statement that a zero-carbon firm resource is needed, the organizations responsible for New York State electric system reliability agree. The New York Independent System Operator (NYISO) 2023-2042 System & Resource Outlook, and Power Trends 2024 analyses and the New York Department of Public Service (DPS) Proceeding 15-E-0302 Technical Conference determined that DEFR was needed. Independent analyses by the Cornell Biology and Environmental Engineering, Richard Ellenbogen, and Nuclear New York also found that it was needed. For example, a very readable description of the DEFR problem by Tim Knauss describing the work done by Cornell’s Biology and Environmental Engineering Anderson Lab found that “Just 15 years from now, the electric grid will need about 40 gigawatts of new generating capacity that can be activated regardless of wind speeds, cloud cover or other weather conditions”.

While this is not directly applicable to the DEFR requirement I want to highlight the following Howarth quote:

Now having said that. There are a lot of details to work out, energy storage is going to be critical. Lisa made the point that ground source heat pumps and thermal networks are better than air source heat pumps. They are hugely more effective in the peak time in January. If we go that route we don’t need as much electrical capacity overall. I would add that thermal storage is cheaper than electrical storage for energy. Particularly if you have a thermal network because you can store heat that can provide a community with heat for weeks to months to even on an annual basis. There is a community in Saskatchewan I believe where they store heat six months at a time which is very cheap compared to other things

I believe Howarth’s thermal network reference is to Calgary’s Drake Landing solar heating community. There is only one problem. The system established in 2006 is failing and will be decommissioned less than 20 years after it was built. In my opinion, the New York Energy Plan must include a critique of the Drake Landing experiment and the implications for New York thermal networks. This is another feasibility analysis that I think is necessary.

Howarth went on to double down on his position that no new technologies are needed:

We don’t need new technologies to meet the goals of our climate law. Mark Jacobson from Stanford, who I think is the most brilliant engineer I know. He and I and others wrote a plan back in 2013, more than ten years ago, laying out specifically how to make the state of New York fossil fuel free on a realistic time frame. We made the case then, more than ten years ago, that we did not need new technologies, and it was cost-effective then. It is even more so now. The whole idea of waiting for the next new technology is an excuse for inaction. We don’t need to wait.

I have assembled a page that describes the analyses that contradict the Jacobson and Howarth work and includes a critique of their results. To adequately characterize the New York electric system, it is necessary to simulate the details of the New York electric transmission system. Not surprisingly, of the 11 New York Control Areas the New York City area requires the most energy. That fact coupled with geographical constraints because New York City is basically a load pocket means that transmission details are important. To characterize wind and solar it is necessary to evaluate meteorological conditions to generate estimates of wind and solar resource production. When that is coupled with projections of future load, the sophisticated analyses all conclude that the new dispatchable emissions-free resource is needed because simply adding much more short-term storage will not work. In my opinion, academic studies like Jacobson and Howarth short-change transmission constraints and/or weather variability leading to false solutions and conclusions.

Advocates for the Scoping Plan energy approach demand action now because the law mandates renewables. Invariably they overlook New York Public Service Law § 66-p (4). “Establishment of a renewable energy program” that includes safety valve conditions for affordability and reliability that are directly related to the zero emissions resource. § 66-p (4) states: “The commission may temporarily suspend or modify the obligations under such program provided that the commission, after conducting a hearing as provided in section twenty of this chapter, makes a finding that the program impedes the provision of safe and adequate electric service; the program is likely to impair existing obligations and agreements; and/or that there is a significant increase in arrears or service disconnections that the commission determines is related to the program”.

Conclusion

The Climate Action Council should have established criteria for the three § 66-p (4) requirements so that there is a clear test to suspend or modify obligations. New York State law has restrictions that protect citizens from irrational adherence to a dangerous energy future and I believe that a feasibility analysis for the new DEFR technology should be part of the evaluation for this mandate.

In my opinion, the most promising DEFR backup technology is nuclear generation because it is the only candidate resource that is technologically ready, can be expanded as needed and does not suffer from limitations of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. If the only viable DEFR solution is nuclear, then renewables cannot be implemented without it. But nuclear can replace renewables, eliminating the need for a massive DEFR backup resource. Therefore, it would be prudent to pause renewable development until DEFR feasibility is proven because nuclear generation may be the only viable path to zero emissions.

Jonah Messinger summarizes my worry that New York has placed undeserved reliance on the work of Robert Howarth:

That an activist scholar with a history of contested and critiqued claims could influence the Biden administration with such an obviously erroneous study is more than concerning. It demonstrates how faulty science in the name of climate can derail important policy debates, and make the global energy transition far harder.

I am sure that none of the advocates who venerate his work will ever be convinced that his work is fatally flawed. However, it is time that the energy experts in the state step up and confront public officials with the reality that the Climate Act schedule and mandates are only possible with a new technology. Evaluating the potential technologies and determining if they can be feasibly implemented affordably and without risking reliability standards is an obvious approach.