On July 18, 2019 New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), which establishes targets for decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing renewable electricity production, and improving energy efficiency. According to a New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) bulletin dated May 10, 2021, the Advisory Panels to the Climate Action Council have all submitted recommendations for consideration in the Scoping Plan to achieve greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions economy-wide. My posts describing and commenting on the strategies are all available here. This post addresses one aspect of the Energy Efficiency & Housing Advisory Panel enabling strategy recommendations, namely heat pump propaganda.

I have written extensively on implementation of the CLCPA closely because I believe the solutions proposed will adversely affect reliability and affordability, will have worse impacts on the environment than the purported effects of climate change, and cannot measurably affect global warming when implemented. I briefly summarized the schedule and implementation CLCPA Summary Implementation Requirements. I have described the law in general, evaluated its feasibility, estimated costs, described supporting regulations, summarized some of the meetings and complained that its advocates constantly confuse weather and climate in other articles. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

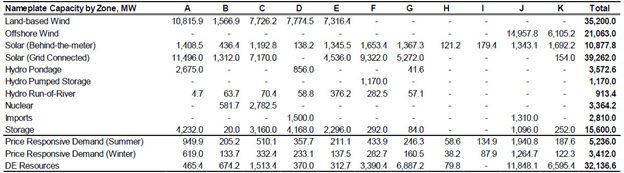

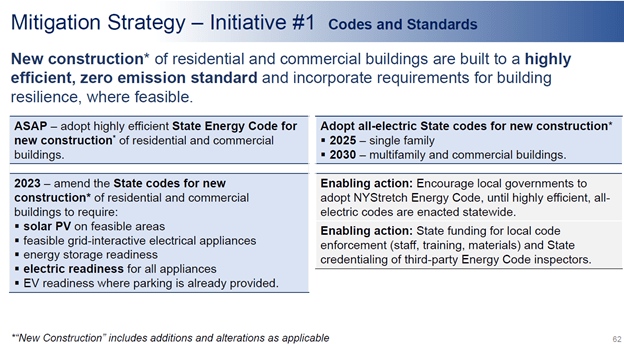

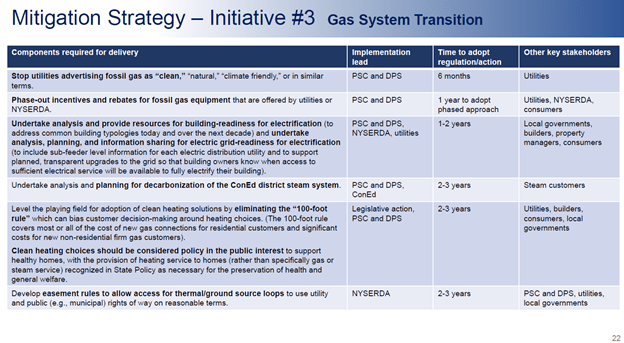

In my post on the Energy Efficiency & Housing Advisory Panel scoping plan recommendations to the Climate Action Council I noted that in their presentation the first mitigation strategy is an initiative to modify building codes and standards as shown in the following slide. The plan is to amend the state codes for new construction, including additions and alterations, to require solar PV on “feasible” areas, grid-interactive electrical appliances, energy storage readiness, electric readiness for all appliance and electric vehicle readiness. They propose to adopt these all-electric state codes for single family residences by 2025 and for multifamily and commercial buildings by 2030. The presentation notes that by 2030, more than 200,000 homes per year will be upgraded to be all-electric and meet enhanced energy efficient standards.

I think garnering support for this initiative is a major challenge for proponents. New York homeowners have extensive experience dealing with winter weather and heating their homes. Selling the changeover to an electric heating system will be a heavy lift particularly for anyone who has lived through a multi-day wintertime electric outage.

The panel recognizes this and included education as a possible mitigant many times throughout their recommendations. For example, one of the components required for delivery for Energy Efficiency & Housing Advisory Panel Enabling Initiative #4: Public Awareness and Consumer Education is to:

Support and scale up multilingual public and consumer education efforts through a large-scale, coordinated awareness, inspiration and education campaign; traditional and broad reaching media, digital communication, “influencer” style campaigns, user-generated campaigns, out of home displays, magazines, mailers, virtual tours; resources for installers, distributors, home-visiting workforce, other supply chain actors to educate consumers, customer-facing resources and tools.

When I read this I cringed because there are so many instances when the climate-related proclamations from the state are not just a little wrong they are off-scale wrong and can only be call propaganda. Propaganda is defined as material disseminated by the advocates of a doctrine or cause. There are many propaganda techniques including “card stacking”. This technique is a feature of the CLCPA:

It involves the deliberate omission of certain facts to fool the target audience. The term card stacking originates from gambling and occurs when players try to stack decks in their favor. A similar ideology is used by companies to make their products appear better than they actually are.

In this post I will present an email I recently received from the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority describing the use of heat pumps for home heating and cooling in the following section. I will then discuss aspects of the email that make heat pumps appear better than they actually are.

Even when the CLCPA was still a proposal it was obvious that electric heating would be necessary to meet the greenhouse gas emission reduction targets proposed. I wrote a post titled Air Source Heat Pumps In New York over two years ago that explains how heat pumps work and describing a research study that showed the problems with heat pumps in cold climates that make them worse than the NYSEDA description. I will summarize the technology and the fundamental problem here but if you are interested in more details, I refer you to my previous post.

According to the Department of Energy heat pumps are very efficient because they move heat rather than converting it from a fuel like combustion heating systems do. Air source heat pumps move energy from the air and ground source heat pumps move energy from underground water. Note that because ground source heat pumps require digging, air source heat pumps are the preferred retrofit technology. Unfortunately, there is a big problem with air source heat pump systems and improperly designed ground source heat pumps. In particular when the weather gets really cold there is insufficient energy in the air or underground water to provide adequate heat when it is transferred.

Myth Buster: The Heat Pump Edition

The following is the text from a NYSERDA email titled “Myth Buster: The Heat Pump Edition”. It also is available in a web link.

With the beautiful days of summer upon us, there’s no better time to reevaluate your home’s current heating and cooling options than right now.

If your current system is reaching its end-of-life or if you’re just looking for ways to save energy and money while keeping your home as comfortable as possible this summer, you may want to consider a heat pump as an alternative heating and cooling option. Heat pumps provide even, clean, and energy-efficient heating and cooling throughout your home, without the random hot and cold spots that other types of heating systems are known for.

You’ve probably heard a few things around heat pumps and the New York State climate that may have you scratching your head, but we’re here to help dispel four of the most common myths around heat pumps to help put your mind at ease.

Myth #1: Heat pumps don’t work in cold climates.

This is one of the most common myths we hear about heat pumps – that they’re only effective in warm environments. The truth is, today’s heat pumps are equipped with the most up-to-date technology that allows them to produce efficient, superior heating in temperatures as low as -13 degrees Fahrenheit. Even in subzero temps, high quality heat pump units can heat up quickly and provide even, comfortable heating without cold spots throughout your home and without the need for supplemental heat.

Myth #2: Heat pumps create heat.

Heat pumps don’t actually create heat — they simply move it from one place to another. Even during the winter, there is some degree of heat that still exists in the air or the ground. Heat pumps remove this heat and transfer it into your home.

Myth #3: Heat pumps are useless during the summer months.

Although they are called “heat pumps,” these systems are actually two-in-one, capable of heating and cooling. During the summer, heat is drawn out of the home, and, through the use of a reversing valve, which essentially flips the flow of coolant through the system, allows air to be cooled before re-entering the home.

Myth #4: There is only one kind of heat pump.

When it comes to heat pumps, you actually have two primary options – a ground source heat pump or an air source heat pump. Also known as a geothermal heat pump, ground source heat pumps draw air from the ground and transfer it evenly into your home, and reverse the process during the summer. Air source heat pumps extract heat from the air outside and distribute it evenly into your home. As with geothermal heat pumps, the process is reversed during warmer months.

Discussion

I will address the propaganda in the components of the NYSERDA email below.

In the introduction, NYSERDA claims “Heat pumps provide even, clean, and energy-efficient heating and cooling throughout your home, without the random hot and cold spots that other types of heating systems are known for.” A moment’s thought raises the question: how can the type of heating system affect hot and cold spots? In order to make a heat pump viable, the structure has to be very well insulated and any air infiltration reduced as much as possible. That kind of structure will reduce the number of random hot and cold spots. As I understand it, the retrofit approach is to replace a fossil-fired furnace with a heat pump replacement. Any random hot and cold spots from issues with the existing duct system won’t be addressed by a heat pump per se. To address those issues the heating system ductwork would have to be replaced. Moreover, in order to make the heat pump viable the insulation and infiltration issues need to be addressed.

The first myth addressed is “Heat pumps don’t work in cold climates”. The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy published a paper that illustrates the cold climate region problem with air source heat pumps: Field Assessment of Cold Climate Air Source Heat Pumps (ccASHP). The report describes a Center for Energy and Environment field study in Minnesota where cold climate air source heat pumps were directly compared to propane and heating oil furnaces. The report notes that “During periods of very cold temperatures when ccASHPs do not have adequate capacity to meet heating load, a furnace or electric resistant heat can be used as backup.” The NYSERDA document does not mention the need for a backup system and, frankly, it is not clear how retaining a fossil-fired backup system will be allowed by the CLCPA. As a result, the backup system will be highly inefficient radiant electric heat.

Figure 2 from the document graphically shows the problem. In this field study homes were instrumented to measure the heat pump and furnace backup usage. Backup furnace usage was relatively low and the heat pump provided most of the heat until about 20 deg. F. For anything lower, heat pump use went down and the furnace backup went up. Below zero the air source heat pumps did not provide any heat and furnace backup provided all the heat. NYSERDA claims “The truth is, today’s heat pumps are equipped with the most up-to-date technology that allows them to produce efficient, superior heating in temperatures as low as -13 degrees Fahrenheit”. Obviously when the temperature is lower than -13 aka when you want heat the most, an air source heat pump is worthless.

The second myth is “Heat pumps create heat”. I have no issue with the response itself but the comment “Even during the winter, there is some degree of heat that still exists in the air or the ground” does not address the flaw described earlier. In particular, there always is some heat in the air but the question is when does the amount of heat become so low that extracting usable heat is not viable.

The third myth is “Heat pumps are useless during the summer months”. This is a great advantage to this technology because they can be used in reverse in the summer to provide air conditioning. In more southerly locations this makes the technology a good choice as long as there is backup heating capability for the rare cold snap.

The last myth is “There is only one kind of heat pump”. I have no issue with this response.

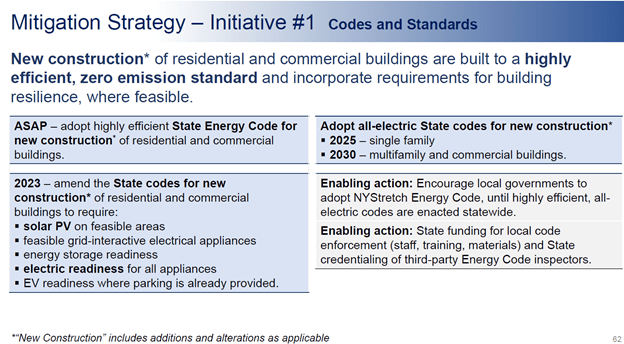

Conclusion

To sum up my discussion, I believe that there are two problems with the plan to deploy air source heat pumps. While air source heat pumps might work most of the time the fact is that when the need for heat is greatest in New York, they won’t provide sufficient heat so a backup system is needed. I believe radiant electric heat will be the preferred option for air source heat pump conversions. When the CLCPA mandate for all electric heating is implemented along with electric vehicles I am sure that local electric distribution systems will have to be upgraded at considerable expense. Ultimately the problem is that these worst-case conditions for heat correspond to the worst annual wind and solar resource availability. Where is the energy for this heating boondoggle going to come from?

In several different proceedings I have voiced my concerns about air source heat pump technology in Upstate New York when temperatures are below zero. In those comments I referenced the results from Field Assessment of Cold Climate Air Source Heat Pumps. I recommended that NYSERDA do a similar analysis using the newer technology that allegedly eliminates the issues raised in the study. The response has been crickets. Until such time that there is a follow up study that supports NYSERDA’s claims and refutes the results of this study, I don’t believe any heat pump propaganda from NYSERDA.

There is another aspect to the plan to electrify home heating. I don’t think the system is going to work well during typical cold snaps and I have serious doubts about the worst-case polar vortex outbreaks. Unfortunately, the very worst case is an electric outage in the winter. I survived a multi-day electric outage in the winter using a gasoline powered generator to provide power to my natural gas furnace. The Department of Energy heat pump description noted that heat pumps move heat because they move heat rather than converting it from a fuel like combustion heating systems do. That overlooks the ability of combustion heating systems to store fuel for use when needed. That is a critical resource for electric outages that proponents of heat pumps ignore.

At the end of the day, I think there will be tremendous pushback when the all-electric heating requirements are rolled out. For me personally, the requirement for an all-electric home is a deal breaker for remaining a resident of the state. I don’t think I am the only one.