At the December 20, 2021 meeting of New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) Climate Action Council the Council voted to release the Scoping Plan for public comment. The Scoping Plan and the presentations on the Integration Analysis that forms the technical basis of the Plan claim that the societal benefits of the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emission reductions are greater than the societal costs. This article expands upon my first impression of costs and benefits especially regarding the alleged benefits of reductions on avoided economic damages caused by climate change.

I have summarized issues with the Climate Act and written extensively on implementation of it because I believe the solutions proposed will adversely affect reliability and affordability, will have worse impacts on the environment than the purported effects of climate change, and cannot measurably affect global warming when implemented. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

The Climate Action Council is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that will “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda”. Starting in the fall of 2020 seven advisory panels developed recommended policies to meet the targets that were presented to the Climate Action Council in the spring of 2021. Over the summer of 2021 the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultant Energy + Environmental Economics (E3) prepared an integration analysis to “estimate the economy-wide benefits, costs, and GHG emissions reductions associated with pathways that achieve the Climate Act GHG emission limits and carbon neutrality goal”. The integration analysis implementation strategies have been incorporated into the draft Scoping Plan. On December 20, 2021 the Climate Action Council voted to release the Scoping Plan for public comment on December 30, 2021.

The presentation on December 20, 2021 revised previous projections. Those projections were not documented the same as the November 18, 2021 update of key results, drivers, and assumptions that were posted on the Climate Act resources page. In the absence of updated resource information I was forced to use information from these documents in the this article:

- Integration Analysis – Benefits and Costs Presentation [PDF]

- Integration Analysis – Initial Results Presentation [PDF]

- Integration Analysis – Key Drivers and Outputs (“Key Drivers”) [XLSX]

- Integration Analysis – Inputs and Assumptions Summary (“Inputs Summary”) [PDF]

- Integration Analysis – Inputs and Assumptions Workbook (“Inputs Workbook”) [XLSX]

Societal Benefits and Costs

The costs and benefits provided in the Integration Analysis and the draft Scoping Plan are societal values. In the Inputs Summary E3 explained that their methodology “produces economy wide resource costs for the various mitigation scenarios relative to a reference scenario”. They produce output on an “annual time scale for the state of New York, with granularity by sector” including “Annualized capital, operations, and maintenance cost for infrastructure (e.g., devices, equipment, generation assets, T&D)” and “Annual fuel expenses by sector and fuel (conventional or low carbon fuels, depending on scenario definitions)”. However, it “does not natively produce detailed locational or customer class analysis”. Consequently, the information needed to determine direct consumer costs will be “developed through subsequent implementation processes”. They also note that the value of avoided GHG emissions calculated is based on guidance developed by DEC.

The following Sectoral Coverage for Cost figure describes the costs included in the Integration Analysis for each sector. The costs listed are direct costs. For example, incremental capital and operating transportation investments cover the direct cost but not the transactional costs such as the additional interest cost for a more expensive electric vehicle loan. In addition, there are analytical choices that could affect costs such as the number of each type of electric vehicle charging systems. Also note that there are cost estimates for technology that has not been deployed at the scale necessary to maintain reliability and for technology that is still under development. Without complete transparency for the calculation estimates it is not possible to evaluate the validity of these cost estimates.

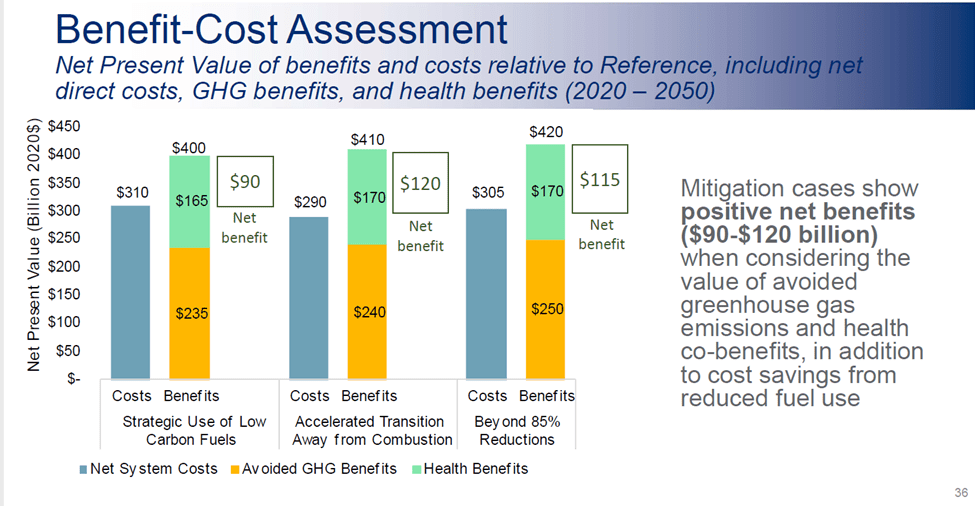

The presentation for the December 20, 2021 Climate Action Council meeting updated the Benefit Cost assessment slides. All three mitigation scenarios are listed now and the values in Scenarios 2 and 3 have changed. A prime message is that the “mitigation cases show positive net benefits ($90-$120 billion) when considering the value of avoided greenhouse gas emissions and health co-benefits, in addition to cost savings from reduced fuel use”. The remainder of this article will discuss the meaning of avoided future climate damage benefits because that is the largest source of the alleged benefits.

Value of Avoided Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) or Value of Carbon is a measure of the avoided costs from global warming impacts out to 2300 enabled by reducing a ton of today’s emissions. This is a complicated concept and I don’t think my explanations have successfully described it well. Fortunately, I believe that Bjorn Lomborg does a very good job explaining it. I highly recommend his 2020 book False Alarm – How Climate Change Panic Costs Us Trillions, Hurts the Poor, and Fails to Fix the Planet (Basic Books, New York, NY ISBN 978-1-5416-4746-6, 305pp.). The following is an excerpt from his chapter What is Global Warming Going to Cost Us?

We need to have a clear idea about what global warming will cost the world. so that we can make sure that we respond commensurately. If it’s a vast cost, it makes sense to throw everything we can at reducing it. If it’s smaller, we need to make sure that the cure isn’t worse than the disease.

Professor William Nordhaus of Yale University was the first (and so far, only) climate economist to be awarded the Nobel Prize in economics in 2018. He wrote one of the first ever papers on the costs of climate change in 1991 and has spent much of his career studying the issue. His studies have helped to inspire what is now a vast body of research.

How do economists like Professor Nordhaus go about estimating the costs of future climate change impacts? They collate all the scientific evidence from a wide range of areas, to estimate the most important and expensive impacts from climate change, including those on agriculture, energy, and forestry, as well as sea-level rises. They input this economic information into computer models; the models are then used to estimate the cost of climate change at different levels of carbon dioxide emissions, temperature, economic development, and adaptation. These models have been tested and peer reviewed over decades to hone their cost estimates.

Many of the models also include the impacts of climate change on water resources, storms, biodiversity, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, vector-borne diseases (like malaria), diarrhea, and migration. Some even try to include potential catastrophic costs such as those resulting from the Greenland ice sheet melting rapidly. All of which is to say that while any model of the future will be imperfect, these models are very comprehensive.

When we look at the full range of studies addressing this issue, what we find is that the cost of climate change is significant but moderate, in terms of overall global GDP.

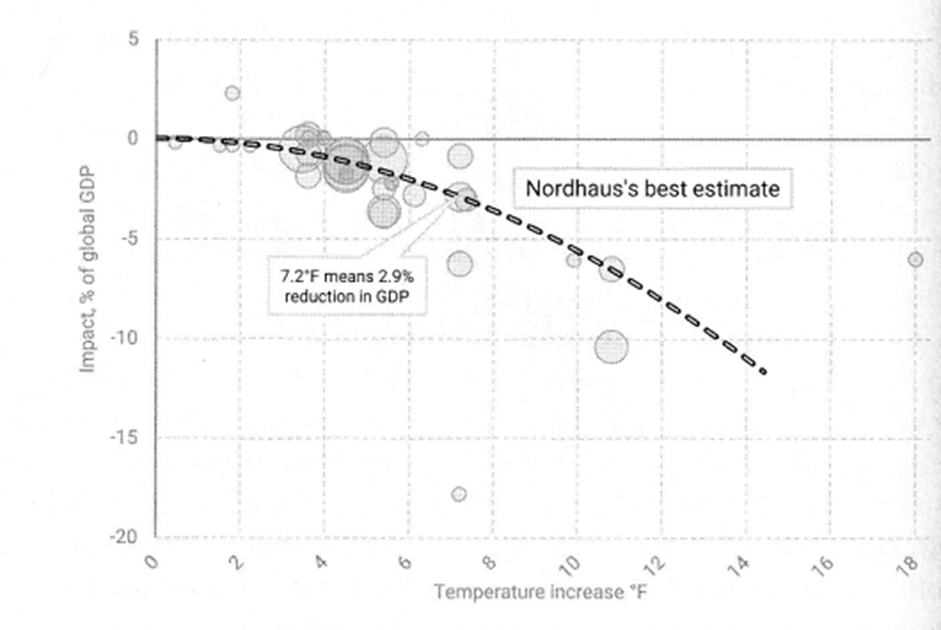

Figure 5.1 shows all the relevant climate damage estimates from the latest UN Climate Panel report, updated with the latest studies. On the horizontal axis, we can see a range of temperature increases. Down the vertical axis, we see the impact put into monetary terms: the net effect of all impacts from global warming translated into percentage of global GDP. The impact is typically negative, meaning that global warming will overall be a cost or a problem.

Right now, the planet has experienced a bit less than 2°F global temperature increase since the industrial revolution. This graph shows us that it is not yet clear whether the net global impact from a 2°F change is positive or negative; there are three studies that show a slight negative impact, and one showing a rather large benefit. As the temperature increase grows larger, the impact becomes ever more negative. The dashed line going through the data is Nordhaus’s best estimate of the reduction in global GDP for any given temperature rise.

We should focus on the temperature rise of just above 7°F, because that is likely to be what we will see at the end of the century, without any additional climate policies beyond those to which governments have already committed. At 7.2°F in 2100, climate change would cause negative impacts equivalent to a 2.9 percent loss to global GDP.

Remember, of course, that the world will be getting much richer over die course of the century. And that will still be true with climate change -we will still be much richer, but slightly less so than we would have been without global warming.

In summary, models are used to project the benefits of reducing GHG emissions on future global warming impacts including those on agriculture, energy, and forestry, as well as sea-level rises, water resources, storms, biodiversity, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and vector-borne diseases (like malaria), and diarrhea. Richard Tol describes the value of greenhouse gas emission reductions thusly: “In sum, the causal chain from carbon dioxide emission to social cost of carbon is long, complex and contingent on human decisions that are at least partly unrelated to climate policy. The social cost of carbon is, at least in part, also the social cost of underinvestment in infectious disease, the social cost of institutional failure in coastal countries, and so on.”

There are some important caveats in this approach. For example, Lomborg does not mention the fact that the models estimate those impacts out to the year 2300 and that the largest impacts are predicted to occur at the end of the modeling period. All of these economic models simplify the relationship between emissions and potential global warming impacts and they all presume a high sensitivity to those impacts from greenhouse gases which is entirely consistent with the Climate Act’s presumed impacts. Finally, keep in mind that there is no attempt to consider advantages of greenhouse gases much less balance them in their projected benefit costs.

New York’s Flawed Avoided Cost Methodology

There is a fundamental flaw in the claim that the Integration Analysis mitigation cases show positive net benefits when considering the value of avoided greenhouse gas emissions. Although I have described these problems with the DEC Value of Avoided Carbon Guidance previously it bears repeating. In my first post I noted that the Guidance includes a recommendation how to estimate emission reduction benefits for a plan or goal. I believe that the guidance approach is wrong because it applies the social cost multiple times for each ton reduced. I maintain that it is inappropriate to claim the benefits of an annual reduction of a ton of greenhouse gas over any lifetime or to compare it with avoided emissions. The social cost calculation that is the basis of their carbon valuation sums projects benefits for every year subsequent to the year the reductions are made out to the year 2300. The annual value of carbon for that year is based on all the damages that occur from that ton over all those years. Clearly, using cumulative values for this parameter is incorrect because it counts those values over and over. I contacted social cost of carbon expert Dr. Richard Tol about my interpretation of the use of lifetime savings and he confirmed that “The SCC should not be compared to life-time savings or life-time costs (unless the project life is one year)”.

In the second post I described how I submitted comments on this topic to DEC and NYSERDA in February and followed up in June. They eventually responded: “We ultimately decided to stay with the recommendation of applying the Value of Carbon as described in the guidance as that is consistent with how it is applied in benefit-cost analyses at the state and federal level.”

There are other problems with their approach. I asked Dr. Tol another question about using the social cost of methane and he pointed out that “the social cost of carbon is an efficiency concept” so it is inappropriate to use social costs in the way that New York is doing. He said that “If a cap is set, you should not use the social cost of carbon. A cap violates efficiency.” I am not an economist and honestly cannot claim to understand this argument but it is pretty clear that New York is pushing the envelope in its use of the social cost of carbon.

The Integration Analysis claims reducing GHG emissions will provided societal benefits of avoided economic damages of between $235 and $250 billion. The more appropriate value is much less. According to §496.4 Statewide Greenhouse Gas Emission Limits (a) “For the purposes of this Part, the estimated level of statewide greenhouse gas emissions in 1990 is 409.78 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, using a GWP20 as provided in Section 496.5 of this Part”. The DEC Value of Avoided Carbon Guidance recommends a social cost of $121 in 2020 and $172 in 2050. If New York had magically eliminated all of the 409.78 million tons of GHG in 2020, the societal benefit of those reductions would have only been $49.6 billion. If all the reductions occurred in 2050 the societal benefit would be $70.5 billion.

Discussion

I used the 2050 societal benefit $70.5 billion estimate to show that Climate Act guidance incorrectly applies the metric by applying the value of an emission reduction multiple times to make the claim that the mitigation scenarios show positive net benefits. The Strategic Use of Low Carbon Fuels scenario is estimated to have $310 billion in net direct costs, avoided carbon damage benefits of $235 billion, and health co-benefits of $165 billion so that the net benefit is $90 billion. However, when the over-counting error is corrected, the avoided carbon damage benefit is only $70.5 billion so there is a negative net benefit is $74.5 billion. The Accelerated Transition Away from Combustion scenario ends up with a negative net benefit of $49.5 billion and the Beyond 85% Reductions scenario has a negative net benefit of $64.5 billion.

The State of New York has never quantified the effect on potential global warming for any of their climate change regulations. In the absence of an “official” number I have adapted the calculations in Analysis of US and State-By-State Carbon Dioxide Emissions and Potential “Savings” In Future Global Temperature and Global Sea Level Rise to estimate the potential effect. This analysis of U.S. and state by state carbon dioxide 2010 emissions relative to global emissions quantifies the relative numbers and the potential “savings” in future global temperature and global sea level rise. These estimates are based on MAGICC: Model for the Assessment of Greenhouse-gas Induced Climate Change so they represent projected changes based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates. All I did in my calculation was to pro-rate the United States impacts by the ratio of different New York inventory emissions divided by United States emissions to determine the effects of a complete cessation of all New York’s emissions. My calculations showed that for the CLCPA Part 496 inventories there would be a reduction, or a “savings,” of between approximately 0.0097°C and 0.0081°C by the year 2100. This savings on global warming from the maximum possible New York emission reductions will be too small to measure. More importantly, New York’s emissions will be negated in a matter of months by greenhouse gas emission increases in countries in the developing world building their energy systems with reliable and affordable fossil fuels.

Advocates for the Climate Act often say we need to act on climate change for our children and grandchildren. However, if a generation is 25 years long, then the avoided cost of carbon societal benefit is applied to 11 generations out to 2300. One of the points that Lomborg makes in False Alarm is that the costs of global warming will only reach 2.6% of GDP by 2100 but that global GDP will be so much higher at that time that this number is insignificant.

New Yorkers also need to be aware that benefits mostly accrue to those jurisdictions outside of New York. To this point they are more vulnerable because there is under-investment in resilient agriculture, energy, and forestry; their society is not rich enough to address sea-level rises like Holland has done for centuries; adaptation for water resources, storms, and biodiversity is not a priority because of poverty; and where underfunding for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, vector-borne diseases (like malaria), and diarrhea makes the impacts of those diseases worse than in New York.

Importantly, if total global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise as countries improve their resiliency to weather events and health care system using fossil fuels then there will not be any actual societal benefits from New York’s emission reductions. The benefits argument devolves into claiming that the value of New York’s avoided greenhouse gas emissions reductions is that impacts would have been even worse without them. New York’s share of global GHG emissions is 0.45% in 2016, the last year when state-wide emissions consistent with the methodology used elsewhere are available, so they can only claim only less than half a percent worse because that is New York’s share of total emissions today.

Conclusion

When the Scoping Plan is rolled out to the public at the end of the year, one of the major talking points will be that the costs of inaction outweigh the costs of implementing the Climate Act. That claim is false because New York State policy guidance incorrectly calculates the Value of Carbon “benefits”. New York’s emission reduction impacts on global warming should only be counted once.

In addition, the cost and benefit numbers are societal values. It is not clear what the actual costs will be after transaction and implementation cost adders are included and it is impossible, at this time, to determine something as important as ratepayer cost increases. The primary purpose of this article was to describe the societal benefit of avoided emissions on global warming impacts. It is clear that the value of carbon societal benefits accrues to generations far in the future and mostly affect jurisdictions outside of New York.

The societal social benefit benefits are imaginary but the societal direct costs, however they are apportioned to New York consumers, will be real. In my opinion, it is inappropriate for the Integration Analysis to claim that the contrived societal benefits outweigh the societal costs without fully explaining who gets the benefits and when they get the benefits. The other missing explanation is that New York’s actions won’t actually affect global warming because we are such a small fraction of the total global emissions. The Climate Act boils down to a virtue signaling symbolic gesture based on contrived benefits that impose real costs on all New Yorkers, including those least able to afford them.

2 thoughts on “Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act Interpreting Societal Cost of Avoided Economic Damages Caused by Climate Change”