This post describes the latest New York State (NYS) GHG emission inventory report that provides data through 2022. The Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) includes a target for a 40% reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 1990 levels by 2030 and the inventory has some implications relative to that target.

I am convinced that implementation of the New York Climate Act net-zero mandates will do more harm than good if the future electric system relies only on wind, solar, and energy storage because of reliability and affordability risks. I have followed the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 500 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. In addition to the 2030 GHG emission target, the electric sector is required to be 70% renewable. The Climate Action Council (CAC) was responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlined how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” The Scoping Plan was finalized at the end of 2022. Since then, the State has been trying to implement the Scoping Plan recommendations through regulations, proceedings, and legislation.

NYS GHG Emissions

At the end of 2024 the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) released the 2024 statewide GHG emissions report (2024 GHG Report). DEC is required by the Climate Act to follow unique inventory requirements. I published an overview post of this greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory that described things that maximize emissions in an apparent attempt to make GHG emissions as large as possible.

Climate Act emissions accounting includes upstream emissions and is biased against methane. Obviously if upstream emissions are included then the total increases but at the same time it makes the inventory incompatible with everybody else’s inventory. There are two methane effects. Global warming potential (GWP) weighs the radiative forcing of a gas against that of carbon dioxide over a specified time frame so that it is possible to compare the effects of different gases. The values used by New York compare the effect on a molecular basis not on the basis of the gases in the atmosphere, so the numbers are biased. Almost all jurisdictions use a 100-year GWP time horizon, but the Climate Act mandates the use of the 20-year GWP which increases carbon dioxide equivalent values.

The 2024 GHG Report includes the following documents:

- Summary Report (PDF)

- Sectoral Report 1: Energy (PDF)

- Sectoral Report 2: Industrial Processes and Product Use (PDF)

- Sectoral Report 3: Agriculture, Forestry, and Land Use (PDF)

- Sectoral Report 4: Waste (PDF)

- Appendix: CLCPA Emission Factors (PDF)

To calculate all the emissions in New York and estimate the upstream emissions it takes DEC, the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) and consultants two years to produce the reports. This article compares NYS GHG inventory electric sector emissions with EPA emissions and GHG emissions through 2022 relative to the 2030 40% reduction target.

Electric Generating Unit Emission Trends

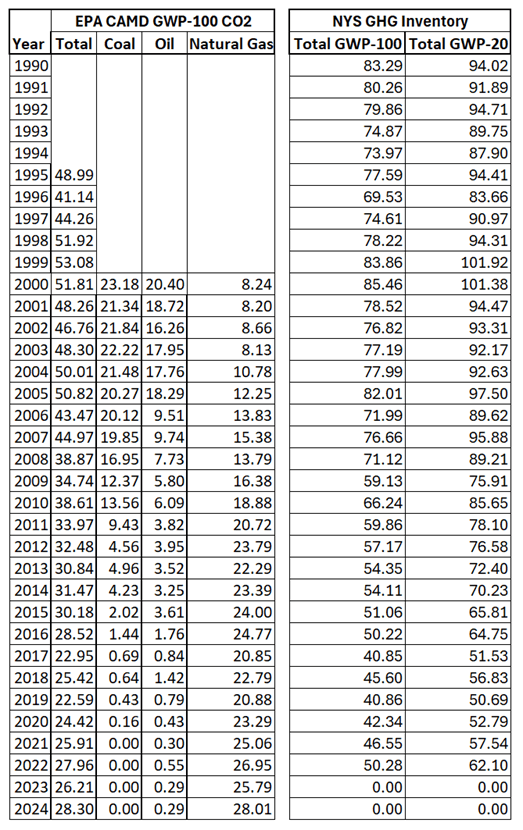

Last month I summarized New York electric sector emissions trends. Electric generating units report emissions to the Environmental Protection Agency Clean Air Markets Division as part of the compliance requirements for the Acid Rain Program and other market-based programs that require accurate and complete emissions data. Table 1 lists the EPA CO2 emissions by fuel type for the available years and the total electricity sector GHG emissions from the NYS GHG Inventory.

Table 1: EPA and NYS Electric Sector Emissions

The EPA electric sector emissions are significantly less than the NYS GHG inventory. There are three primary reasons: the inclusion of upstream emissions, imported electricity emissions, and including three other greenhouse gases: methane (CH4), nitrous oxide N2O, and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). Note that the choice of the GWP-20 rather than GWP-100 increases the final numbers further.

2022 GHG Emissions

Table ES.2 in the Summary Report presents emissions for different sectors. Electric generation emissions are listed as electric power fuel combustion, imported electricity, and as part of imported fossil fuels. In 2022, GHG gas emissions from electric power fuel combustion totaled 27.79 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (mmt CO2e) using a 20-year global warming potential. Imported electricity totaled 8.71 mmt CO2e. Fuel combustion and imported electricity emissions were primarily CO2. The Table ES.2 imported fossil fuel value shown covers all fossil fuel used in other sectors.

NYS GHG Emissions Data

There is one notable feature of the GHG inventory. DEC and NYSERDA previously conducted an analysis of statewide emissions in 1990 to establish a baseline for the “Statewide GHG Emission Limits” established by ECL 75-0107 and reflected in 6 NYCRR Part 496. It is important to understand that GHG emission inventories are not based completely on measured emissions. The EPA CAMD data are based on direct measurements but all the other estimates are derived using emission factors and estimates of activities such as fuel use or vehicle miles traveled. The last four emission inventories all have estimated a different 1990 value than the regulatory limit in Part 496. The report notes “The 6 NYCRR Part 496 regulation may be revised at a later date using updated information. For your information, I have compiled all four tables explaining the differences between the estimate of gross statewide emissions in 1990 from the 6 NYCRR Part 496 rulemaking and in this report.

Trends in Sectors

The 2022 GHG Inventory includes four sectoral reports for energy, industrial processes and product use, agriculture, forestry and land use, and waste. The Summary Report describes the observed trends:

In Figure ES.2, emissions are organized into the sectors described in the IPCC approach (IPCC 2006). The Energy sector encompasses emissions associated with the energy system, including electricity, transportation, and building/industrial heating. The Industrial Process and Product Use (or IPPU) sector covers emissions associated with manufacturing and manufactured products. The Waste sector encompasses any activities to manage human-generated wastes. Finally, the Agriculture, Forest, and Other Land Use (or AFOLU) sector encompasses emissions from the management of lands and livestock as well as net emission removals from land management and the long-term storage of carbon in durable goods.

The Energy sector represents the majority of emissions (76%, 2018-2022), but energy emissions in 2022 were 17.7% lower than in 1990 (Figure ES.2). The overall reduction in energy emissions was offset by increases in all other sectors and by a 1.7% decline in net emission removals. The largest increases occurred in IPPU due to the increasing use of hydrofluorocarbons (4.66mmt CO2e) and in AFOLU resulting from changes in agricultural practices (2.37mmt CO2e). Waste sector emissions declined by 4.36mmt COze over the period, primarily due to implementation of landfill gas capture systems.

Discussion

The implications of the GHG inventory are important. The Climate Act includes a target for a 40% reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 1990 levels by 2030. The NYS Part 496 1990 baseline emissions were 404.26 million metric ton (mmt) CO2e. The total 2022 NYS emissions were 371.38 mmt CO2e which is only a 9% or 37.9 mmt CO2e reduction from the baseline. The 2030 limit is 245.9 mmt CO2e which will require a further 34% or 163.4 mmt CO2e reduction.

It is beyond the scope of the GHG inventory to provide any commentary regarding the achievability of meeting the 2030 target, but it is clear that, absent a miracle, the targets will not be met. It is time for the Hochul Administration to acknowledge that the 2030 targets cannot be achieved. The Climate Act requires that the Public Service Commission (PSC) issue a biennial review for notice and comment that considers “(a) progress in meeting the overall targets for deployment of renewable energy systems and zero emission sources, including factors that will or are likely to frustrate progress toward the targets; (b) distribution of systems by size and load zone; and (c) annual funding commitments and expenditures.” The draft Clean Energy Standard Biennial Review Report released on July 1, 2024 will fulfill this requirement. The final report was due at the end of 2024 but was delayed on December 17, 2024. The draft document compared the renewable energy deployment progress relative to the Climate Act goal to obtain 70% of New York’s electricity from renewable sources by 2030. It projects that the 70% by 2030 goal will not be achieved until 2033 when historic renewable resource deployments are considered. The report did not address the 40% reduction of GHG emissions by 2030 target.

The Climate Act has always been a political ploy to gain favor with certain constituencies and has had little basis with reality. Nowhere is the missing link to reality starker than regarding the implementation of emission reduction programs. The green narrative is that the transition away from fossil fuels will be economic, simple, and only a matter of political will. The reality is completely the opposite. The fact is that to reduce GHG emissions to zero as mandated means that existing energy use of fossil fuels requires replacement of existing infrastructure, development of additional supporting infrastructure, and development of new implementation resources (supply chains and trained trades people). To compound the challenge the Climate Act schedule was not developed on the basis of a rational plan. Instead, the politicians arbitrarily chose the deadlines. We are now seeing the results of this boondoggle and the ramifications are unclear.

Conclusion

The 2024 GHG emission inventory reports should be a wake-up call regarding Climate Act implementation. It is clear that the 2030 GHG emission reduction target cannot be met. In addition, the transition of the electric generating system requires a new technology to ensure reliability and the Hochul Administration has not yet responded to last summer’s Comptroller report that found that: “While PSC and NYSERDA have taken considerable steps to plan for the transition to renewable energy in accordance with the Climate Act and Clean Energy Standard, their plans did not comprise all essential components, including assessing risks to meeting goals and projecting costs.” It is obvious that that New York State should pause implementation of the Climate Act and address the myriad issues uncovered to date.