The February 2026 report Cap and Invest to Meet New Yorkers’ Needs, (Needs Report) published by Spring Street Climate Fund and New Yorkers for Clean Air, is the latest in a series of advocacy documents designed to sell the New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) program to legislators and the public. This article explains why this article misinforms New Yorkers about the supposed benefits of NYCI.

I have extensive experience with market-based pollution control programs. I have been involved in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) program process since its inception and have frequently written about the details of the RGGI program. I have worked on every cap-and-trade program affecting electric generating facilities in New York including RGGI, the Acid Rain Program, and several Nitrogen Oxide programs. I have also been following the NYCI program and other similar programs in New York The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated

Overview

I have described the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) NYCI regulations in many articles. DEC was supposed to promulgate three implementing regulations by 1/1/2024. Currently DEC has only finalized the Mandatory GHG Emissions Reporting Rule. There have been no suggestions when the two other necessary regulations will be proposed. The Cap-and-Invest Rule will define affected sources, binding caps, and allowance allocations. DEC also needs an auction rule that implements the auction that will be used to distribute allowances.

The lack of regulations is a problem. On 3/31/25 a group of environmental advocates filed a petition pursuant to CPLR Article 78 alleging that DEC had failed to comply with the timeframe for NYCI because DEC missed the January 1, 2024 date. I explained that the decision on the petition stated: DEC must “promulgate rules and regulations to ensure compliance with the statewide missed statutory deadlines and ordered DEC to issue final regulations establishing economy-wide greenhouse gas emission (GHG) limits on or before Feb. 6, 2026 or go to the Legislature and get the Climate Act 2030 GHG reduction mandate schedule changed.” On 11/24/25 DEC appealed the decision to the Appellate Division. This means that the deadline of Feb 6 is suspended until the Appellate Division rules. Therefore, the State has no risk of being held in contempt and can safely ignore the deadline. However, the decision was clear – promulgate the regulations or change the law.

On February 26, 2026 the Hochul Administration “leaked” a New York Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) memo that said that “full compliance with New York’s 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act could cost upstate households more than $4,000 a year – on top of what they are already paying today and gas prices could jump over $2 a gallon.” David Catalfamo explains what is going on:

Hochul wants to roll back parts of the CLCPA. She knows it’s politically complicated. So rather than saying so plainly, she lets her budget director hint at it, lets a NYSERDA memo circulate through the press, and then steps in front of a camera to say she’s just responding to the data. It’s Albany smoke-signaling at its finest.

City and State recently published Activists dispute Hochul’s claims about cost of complying with climate law by Rebecca Lewis that describes the Needs Report. It “highlights potential benefits of a cap-and-invest program, including energy rebates for millions of households.” She notes that the “new report from New Yorkers for Clean Air and Spring Street Climate Fund aims to balance out conversations on the potential impacts of hitting climate goals by illustrating the benefits, rather than the costs, of implementation.” This article looks into these claims.

Follow the Money

Last January I reviewed a report from Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and Greenline Insights that claimed New Yorkers will “realize significant economic benefits, including household savings and new job creation, with the Clean Air Initiative” based on an evaluation of all aspects of NYCI. (Clean Air Initiative is a rebranding of NYCI – it is the same thing.) The Needs Report only addresses the investment benefits. Appendix A: Methodology describes three methodology steps: use one of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) price ceiling scenarios to determine the amount of money available, assume “average operational costs of 4% across the board to implement and operate the cap-and-invest program”, and then propose how the remaining 96% could be spent on affordability measures and direct investments.

This is not a serious analysis. It assumes 4% average operational costs. There is an existing cap-and-invest program for the utility industry called RGGI. A serious analysis would have checked the most recent RGGI Operating Plan Amendment to determine what the operating costs were for that program. I found that operating costs in the latest budget for RGGI investments was 8%. I think being off by a factor of two is substantive.

The organizations behind the Needs Report are advocacy groups with a vested interest in NYCI implementation, not independent analysts. Spring Street Climate Fund is characterized as “a left-of-center advocacy group that supports environmentalist legislation within New York State,” funded by the Park Foundation and the Lily Auchincloss Foundation. Evergreen Action “donate now” link features the statement “leading an all-out national mobilization to defeat the climate crisis”.

Environmental activists are pushing back against the NYSERDA memo because it argues that NYCI is unaffordable. The activists are missing a fundamental point. The memo calculates the costs necessary to “fully comply with CLCPA’s current emissions targets with a cap-and-invest program”. To do that the regulation must omit limits on potential allowance prices and will allocate allowances based on the trajectory required to meet the Climate Act mandates. This causes a sharp uptick in projected costs compared to previous analysts.

Appendix A: Methodology notes that the analysis used Scenario C from a NYSERDA analysis in 2024. The ten-year revenue stream is $57.4 billion and includes limits on allowance prices. The NYSERDA memo assumed higher allowance prices would occur if there were no limits on prices and that it would be necessary to implement NYCI consistent with the Judge’s ruling. Using their assumptions, I estimate that the ten-year revenue stream would be five times higher at $295 billion over ten years.

The Needs Report frames $57.4 billion as revenue the state can “invest,” but this is money taken from households and businesses through higher energy costs, higher fuel prices, and higher costs for goods and services. The NYSERDA memo states:

Absent changes, by 2031, the impact of CLCPA on the price of gasoline could reach or exceed $2.23/gallon on top of current prices at that time; the cost for an MMBtu of natural gas $16.96; and comparable increases to other fuels. Upstate oil and natural gas households would see costs in excess of $4,000 a year and New York City natural gas households could anticipate annual gross costs of $2,300. Only a portion of these costs could be offset by current policy design.

One of the flaws of the Needs Report is that it ignores opportunity costs. Even a non-economist like me understands that if an analysis does not consider how the money raised by NYCI might have been used elsewhere is not considered, then their economic benefits claims are biased. My article on the report from Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and Greenline Insights included a discussion of this flaw so I will not repeat it here.

Benefits

The Needs Report simply lists how $57.4 billion could be spent. Listing spending categories is not the same as demonstrating net economic benefits. It describes beneficial spending on energy rebates ($270/yr for 6.5 million households), weatherization (500,000 homes), rooftop solar (400,000 homes), heat pumps (250,000 homes), grid expansion ($3 billion), schools ($5.8 billion), and other categories.

I am not going to address each of these recommendations because the choices and options listed seem to me more tailored to drumming up support for NYCI than anything else. Anyway, these are proposed expenditures, not demonstrated results that do not reflect lessons learned from the investment of RGGI proceeds. It is also flawed because it assumes idle resources—that workers and capital redirected to clean energy would not otherwise have been productively employed. With New York at record employment levels, this assumption is untenable.

Past Performance

Past performance does not guarantee future success, but a record of failure often predicts continued trouble. I have two concerns that are not addressed by either report that are evident in the RGGI program.

A cap-and-invest program has two overarching goals: emission reductions using a declining cap that limits emissions and provide funds for investments in programs that drive emission reductions. However, these goals are often overlooked. Governor Hochul’s core principles for NYCI are affordability, climate leadership, creating jobs and preserving competitiveness, investing in disadvantaged communities, and funding a sustainable future. Only the last principle addresses the overarching goals. The other principles provide guidance for how the money should be spent on political objectives.

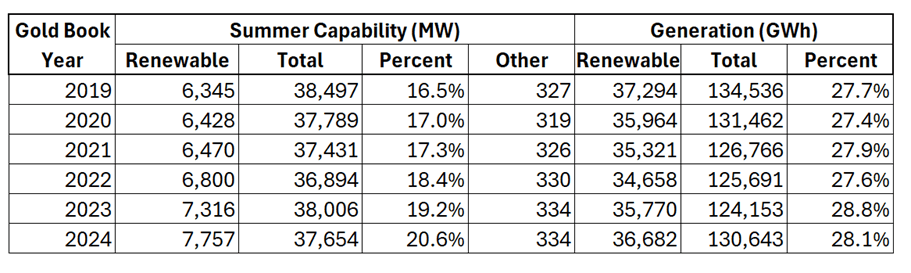

The second problem is that the Needs Report cites RGGI as proof that “similar policies have been humming in our state for years.” NYCI supporters note that since the start of RGGI in 2009 emissions for units in that program are down 33%. However, I have shown that the reason emissions have dropped is because NY power plants switched from using coal and oil to using natural gas because it was cheaper. Moreover, New York does not have a good emission-reduction track record when it comes to investment results from the existing RGGI cap-and-invest program. Investments of RGGI auction proceeds only reduced emissions 4.2% and there should be no expectation that NYCI investments will fare much better. The sources affected by NYCI do not have any cost-effective fuel switching alternatives that can provide reductions like those observed in the utility sector. Unless NYCI emphasizes investments in programs that produce cost effective reductions then emissions will not fall as needed. The NYCI cap on emissions means that energy will be rationed, if it appears that emissions will exceed the cap.

Rebates

The Needs Report explains that NYCI will dedicate at least 30% of its revenue, the largest slice of the program’s pie, to lowering energy costs for working families. The report claims that “these direct rebates are a central feature of the Clean Air Initiative and stand to lower the skyrocketing cost of living for millions of New Yorkers.”

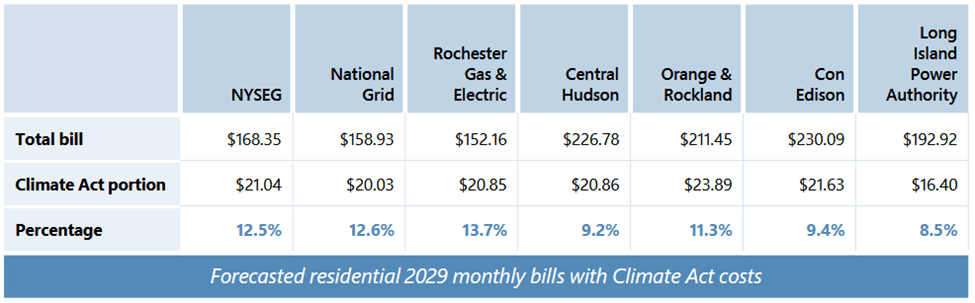

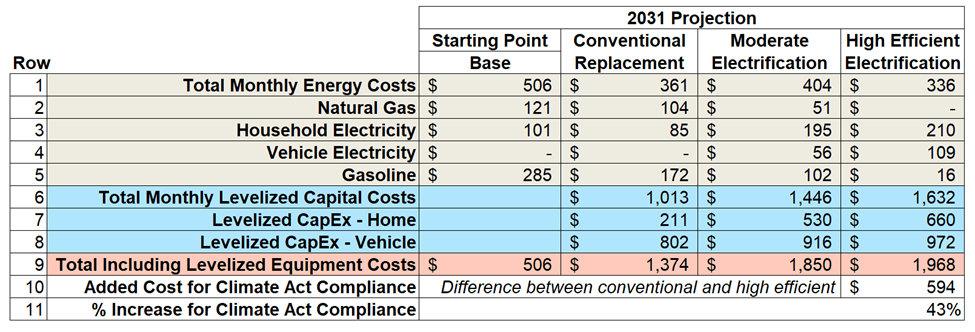

However, the math shows that NYCI makes energy more expensive and only gives back a fraction of the increased costs. The Needs Report states that the 10-year revenues are $57.4 billion, the annual 30% set-aside for rebates is $1.72 billion and the annual rebates are $270 per household. Using the NYSERDA memo projections I estimate that the 10-year revenues are $295 billion, the annual 30% set-aside for rebates is $8.84 billion and the annual rebates will be $1,360 per household. The NYSERDA memo projects household cost increases of $3,000–$4,100 per year. A $1,360 rebate offsets roughly 33-45% of those increased costs. This is the textbook definition of a shell game: raise costs by thousands, rebate a fraction of the costs, and claim it as a “benefit.”

Overall, if cap-and-invest revenues are projected at $295 billion over a decade, that is approximately $29.5 billion per year extracted from the economy. Giving back $1,360/per household to 6.5 million households costs roughly $8.85 billion—less than one-third of what is taken. I remain unimpressed.

Electrification Support

There is another unacknowledged issue. The report assumes massive electrification (heat pumps, EVs, building retrofits) without addressing whether the electric grid can support the added load. NYISO projects significant increases in electric load going forward, with electrification strategies and large load facilities (including data centers) adding substantial demand. The State Energy Plan found that “current renewable deployment trajectories are insufficient to meet statutory targets” and that the necessary acceleration in clean energy deployment is “infeasible today” due to “lack of market capacity”. This all puts pressure on the ability to meet the NYCI cap on emissions which in turn increases the need for effective emission reduction investments.

Discussion

The Needs Report follows the same formula documented in the earlier EDF/Greenline Insights report that I found had problems: benefits were overstated, costs were minimized or ignored, and the methodology was designed to produce a predetermined conclusion. It looks like the report was released as a political counter to the NYSERDA memo documenting the real costs of CLCPA compliance. It was produced by advocacy organizations with a financial and institutional stake in the program’s implementation. It only addresses investment priorities and could not even come up with a reasonable estimate of operational costs. This is not credible support for NYCI.

Conclusion

New York GHG emissions are less than one half of one percent of global emissions and global emissions have been increasing on average by more than one half of one percent per year since 1990. New York actions are not going to affect global warming. There is a fundamental question that the report refuses to answer: if New Yorkers are going to see $295 billion extracted from their wallets over the next decade, would they be better off keeping that money and spending it according to their own priorities? Until advocates can answer that question honestly, reports like this deserve to be recognized for what they are—lobbying documents, not economic analysis.