Politico’s Marie French recently reported that “Two reports backed by environmental advocates found distributing money raised from a cap-and-trade program would leave households better off.” New York’s Affordable Energy Future included recommendations for allocating the revenues from the New York Cap-and-Invest program. I did not address the primary claim but did calculate the expected emission reductions from the investments in the proposed allocations to the reductions needed to meet the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) 2030 and 2050 targets.

I have been involved in the RGGI program process since it was first proposed prior to 2008. I follow and write about the details of the RGGI program because the results of that program need to be considered for Climate Act implementation. The opinions expressed in these comments do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. It includes an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% GHG reduction by 2030. The Climate Action Council (CAC) was responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlined how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” The Scoping Plan was finalized at the end of 2022 and included a recommendation for a market-based economywide cap-and-invest program.

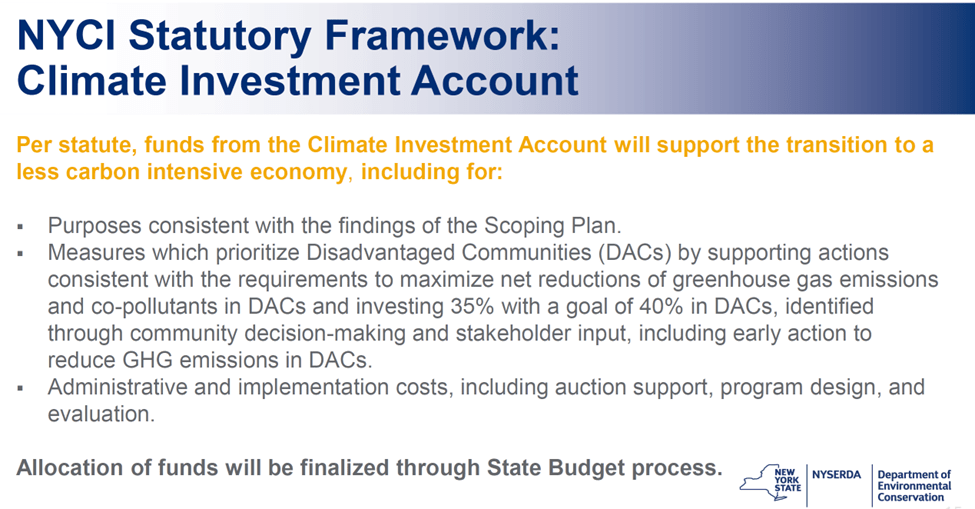

In response to that recommendation, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSEDA) have been preparing implementation regulations for the New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) program. The program works by setting an annual cap on the amount of greenhouse gas pollution that is permitted to be emitted in New York: “The declining cap ensures annual emissions are reduced, setting the state on a trajectory to meet our greenhouse gas emission reduction requirements of 40% by 2030, and at least 85% from 1990 levels by 2050, as mandated by the Climate Act.” In addition to the declining cap, it is supposed to limit potential costs to New Yorkers, invest proceeds in programs that drive emission reductions in an equitable manner, and maintain the competitiveness of New York businesses and industries. I recently summarized some of my concerns with the proposed program.

My decades long experience with market-based pollution control programs has always been from the compliance side. Starting with the Acid Rain Program in 1990 I spent 20 years tracking electric generating station emissions, submitting emissions data to EPA, and working internally to assure that the compliance obligations of the company were assured before I retired. Over that period, DEC and EPA modified the regulations setting the caps on emissions. I was responsible for evaluating whether the company could meet the new caps. When EPA set new limits, the new standard was based on an evaluation of what the generating units could do, arguments revolved around whether their assessment was appropriate for individual units, and whether their schedule for implementing the new limits was achievable. The Climate Act mandates were arbitrary with no regard to feasibility of limits or timing.

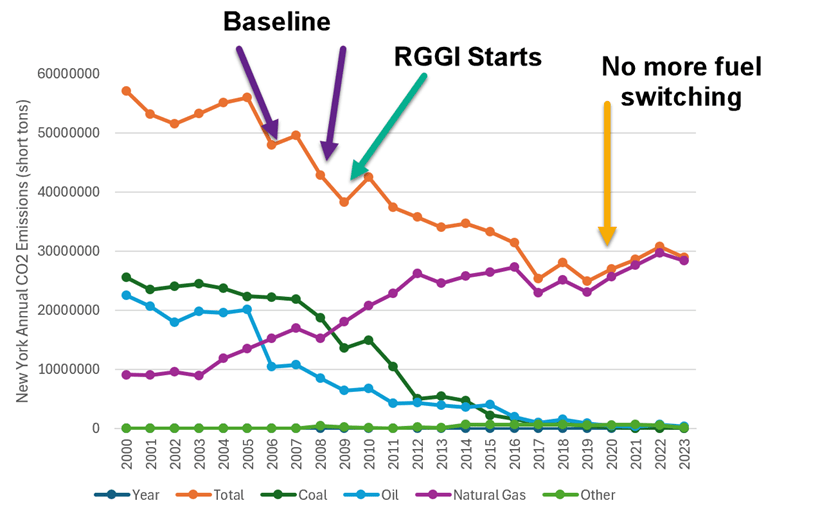

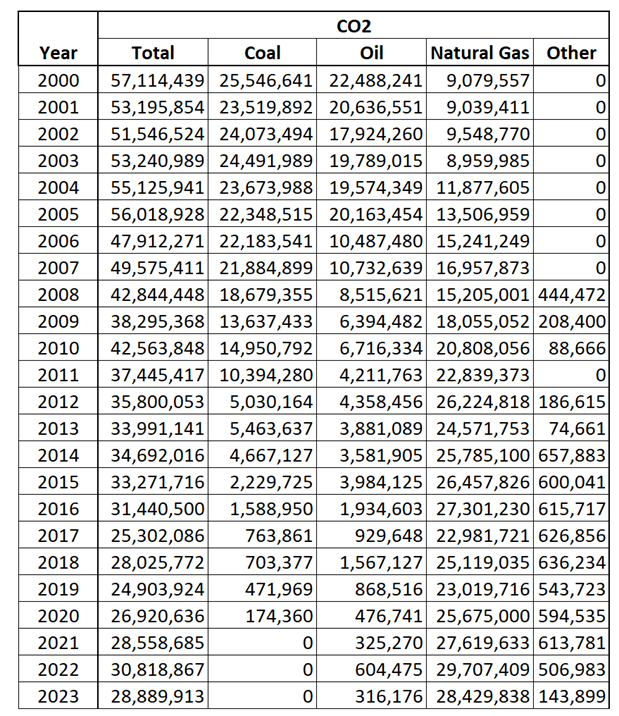

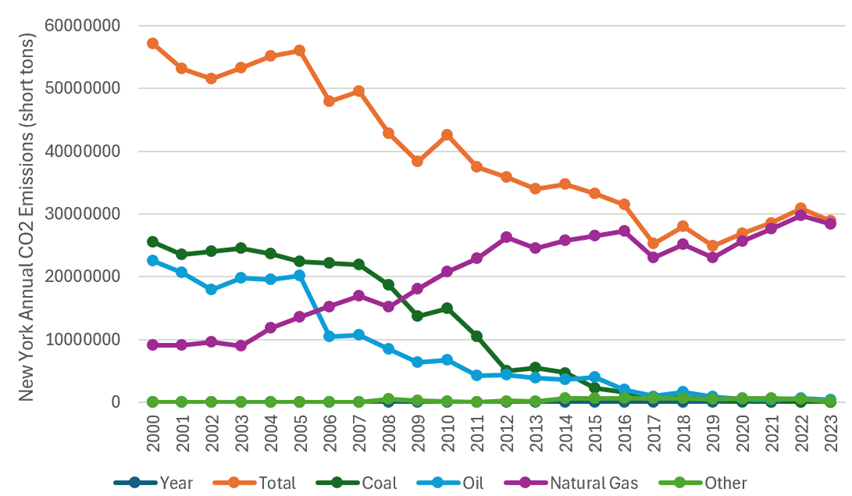

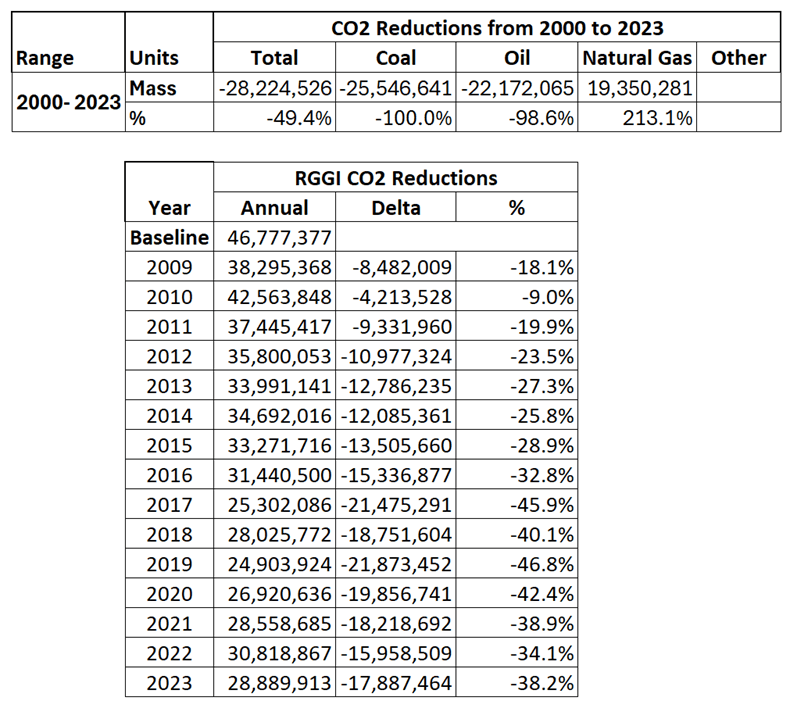

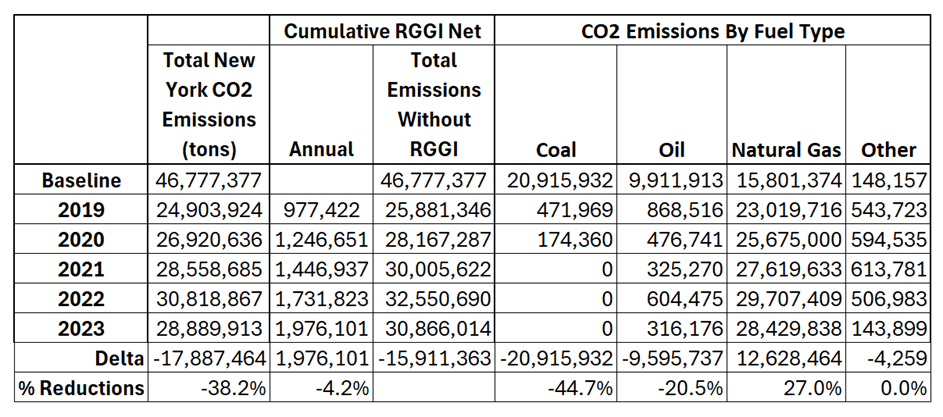

One of the concerning elements of NYCI is the near total disregard for the compliance obligations of affected sources. Last month I evaluated the performance of RGGI relative to compliance obligations in a series of three articles. In the first article I evaluated Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) emission data and NYSERDA documentation and found that the investments funded by RGGI auction proceeds would have been only 4.2% higher if the NYSERDA program investments did not occur. In the second article I showed that the cost per ton reduced from the NYSERDA RGGI operating plan investments was $582 per ton of CO2. The final article described the program allocations in the NYSERDA 2025 Draft RGGI Operating Plan Amendment. I showed that the observed 49% emission reduction since 1990 were primarily due to fuel switching and there are no more fuel switching opportunities available. These analyses also generated a cost per ton of CO2 removed for different NYSDERDA programs that was used in the following analysis.

New York Affordable Energy Future

One of the reports described by Marie French “was produced by Switchbox and paid for by WE ACT for Environmental Justice, Environmental Defense Fund, and Earthjustice”. The recommended citation is

Smith, Alex, Rina Palta, Max Shron, and Juan-Pablo Velez. 2025. “New York’s Affordable Energy Future.” Switchbox. January 13, 2025. I will refer to the report as Smith et al., 2025. I asked Marie about Switchbox and she explained that it was “set up basically to do research for environmental groups in NY/other parts of the country. The project is described by Earthjustice here.

This kind of report bothers me because it is grey literature. One description of grey literature emphasizes the point that it is not subject to peer review but another claims that “it may be the best source of information on policies and programs”. My problem with grey literature performed at the behest of environmental advocacy organizations is that those organizations promote the results without acknowledging the biases. Incredibly, these reports have impacted New York policy. Policy makers cite these works without critical appraisal of the analyses and citations used. The biggest problem is when policy makers neglect to account for potential publication bias when including grey literature in their decision-making process. Of course, I must admit that all of my work is grey literature. The reason that my articles are so long is because I provide the background and data necessary for my readers to assess my results and conclusions. I included this discussion because this report is unique as it is only available on-line at the Switchbox website. That makes assessment of their analysis and data more difficult which I think is the point of that approach.

Program Allocations

French notes that this report focuses on how the revenue from “cap and invest” should be spent and how households could benefit from electrifying their homes. Two revenue scenarios corresponding to the range of expected proceeds proposed by NYSERDA and DEC were analyzed:

- Scenario A would set a $24 per-unit ceiling on allowances in 2025, rising to $26 in 2026, $58 in 2027, and by 6% annually thereafter.

- Scenario C would set a $14 per-unit ceiling on allowances in 2025, rising to $15 in 2026, $27 in 2027, and by 6% annually thereafter.

Smith et al., 2025 state that:

In 2030, the state would collect $6 billion in NYCI revenue under scenario C, and $13 billion under scenario A.

These sums would cover 54 – 115% of NYSERDA’s 2030 cost estimate and are equivalent to 3 – 5% of New York State’s $237 billion 2025 budget.

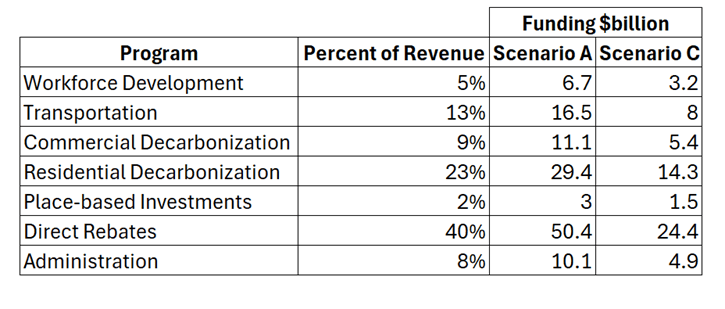

Their proposed funding scenario allocates resources to seven categories (Table 1). In the revenue projections examined by the report, NYCI would raise a total of between $61 – $126 billion over the first 11 years of the program.

Table 1: Funding by program under proposed spending program with 11-year total revenues

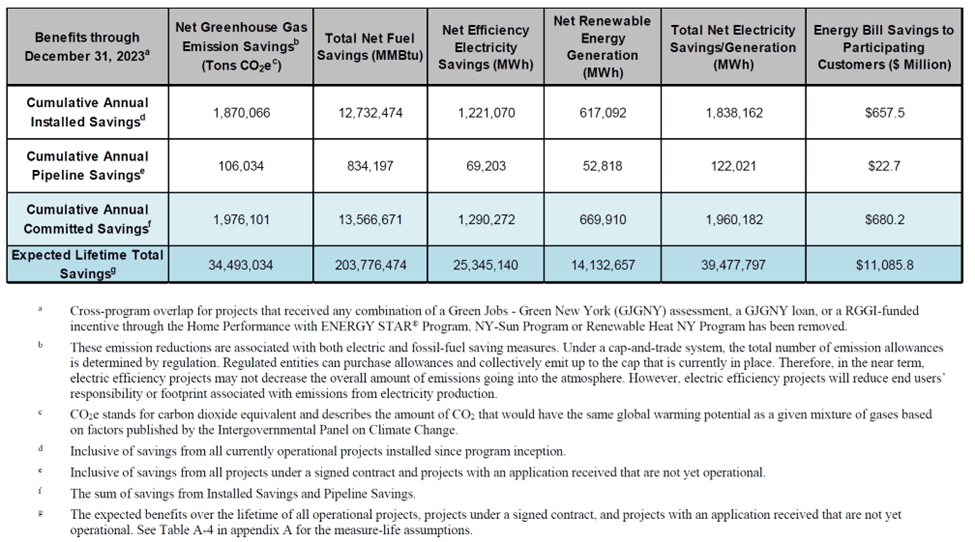

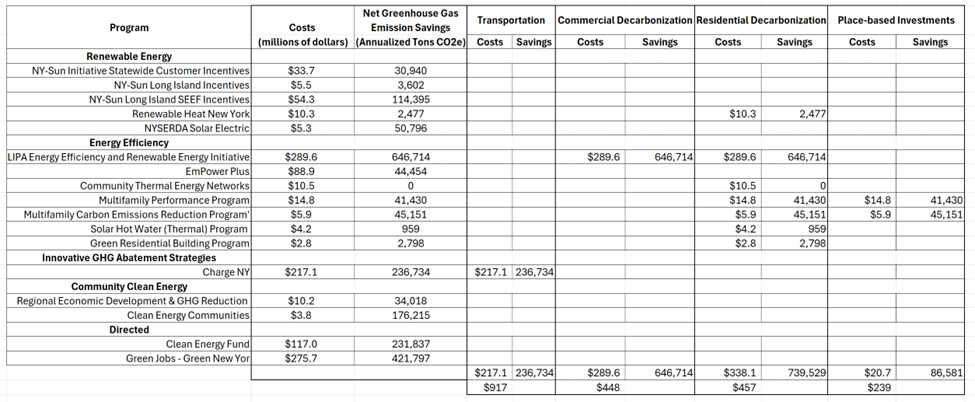

The NYSERDA RGGI Funded Program Status reports provide estimates of the effectiveness of the programs that NYSERDA manages using RGGI proceeds. Table 2 uses data from NYSERDA’s Table 2. Summary of Expected Cumulative Annual Program Benefits through December 31, 2023 in the most recent status report. The costs and emission savings columns in Table 2 are directly from the NYSERDA report. I assigned different NYSERDA programs to the proposed programs in Smith et al., 2025 in the remaining columns. For example, the NYSERDA Charge New York programs support infrastructure deployment for electric vehicles. I summed up all the relevant costs and benefits and calculated a cost effectiveness for each category by dividing the total costs by the expected emission savings:

- Transportation: $917 per ton of CO2e removed

- Commercial Decarbonization: $446 per ton of CO2e removed

- Residential Decarbonization: $457 per ton of CO2e removed

- Place-based Investments: $239 per ton of CO2e removed

Table 2: Summary of Expected Cumulative Annualized Program Benefits through 31 December 2023 Categorized by Smith et al, 2025 NYCI Proposed Programs

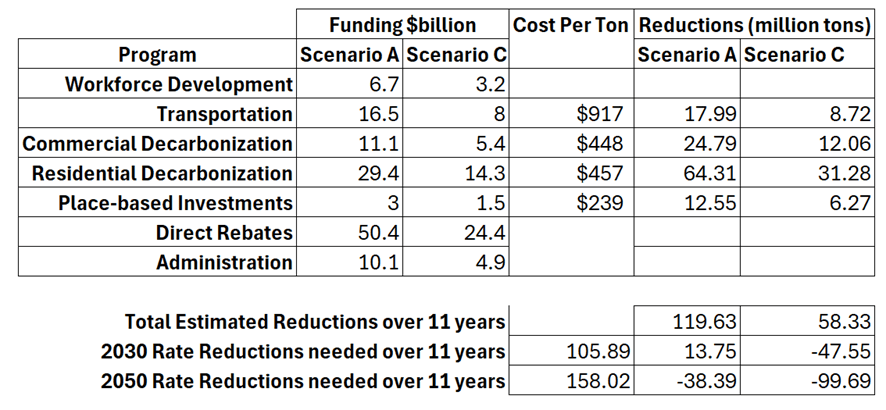

Combining these data, it is possible to determine how effective the proposed allocations will be for providing the emission reductions necessary to meet the Climate Act goals. The expected reductions in each for each program equal the funds available divided the cost per ton expected. The question is whether the investments will achieve compliance. The Scoping Plan did not provide a schedule for emission reductions expected for their reduction strategies, so we must do our own estimate. In 2022, the total GHG emissions for New York equaled 371.08 million tons. In 2030 GHG emissions must meet a 40% reduction of 1990 emissions or 294.07 million tons. To get to that level emissions must go down 9.6 million tons per year. For Scenario A we expect to reduce emissions 119.63 million tons and there is a surplus of 13.75 million tons over the 11 year period total to reach the 2030 target. However, Scenario C does not meet the target and the 2050 target will not be met for either scenario.

Table 3: Funding by program , expected cost efficiency and projected 11-year reductions

Discussion

While most advocates do not acknowledge that cap-and-invest programs probably will not guarantee compliance with the emission reduction goals, this report did. One of the features of the proposed program is a price ceiling on the allowance cost that will limit the impact on consumers. Smith et al., 2025 note that “This is why economists often describe a price ceiling as converting cap-and-trade into a carbon tax at that price point.” In my opinion NYCI is simply a re-branded carbon tax. The authors’ described price ceilings:

However, they have the effect of weakening the cap: if the auction price ended up being higher than the price ceiling for a given year, the state would sell unlimited allowances at the ceiling price, resulting in more allowances sold than the cap would otherwise allow.

Price ceilings therefore sacrifice the state’s ability to control the level of climate pollution in exchange for the ability to control the price of climate pollution. A declining cap would thus be unable to single-handedly decarbonize New York by 2050, and Cap-and-Invest would need to be paired with complementary policies.

There is a reference to the last sentence that states “As documented in the book Making Climate Policy Work (Cullenward and Victor 2020), this is true of all real-world cap-and-trade systems.” In a recent article I made the same point that Cullenward and Victor believe that the level of expenditures needed to implement the net-zero transition vastly exceeds the “funds that can be readily appropriated from market mechanisms”. The numbers derived from the New York RGGI experience corroborates that conclusion.

I worry that there are limited emission reduction options for the compliance entities. There are no add-on controls that can achieve zero emissions for any sector. The only strategy is to convert to a different source of energy which takes time because some components are out of the control of the entity that is responsible for compliance. For example, fuel suppliers are responsible for transportation sector compliance, but the strategy is to convert to zero-emission vehicles. They have no control over that. As noted previously, the Climate Act schedule was determined by politicians. I have long argued that New York needs to do a feasibility study to confirm that the Scoping Plan emission reduction strategies themselves and the arbitrary schedule of the Climate Act are possible.

The problem with NYCI is that it establishes a compliance schedule. If the schedule or the reduction technologies are not feasible, then there will be compliance implications. Organizations are unwilling to knowingly violate compliance requirements because the programs are designed to severely penalize non-compliance. The only remaining option for the fuel suppliers to ensure compliance is to simply stop selling fuel. I do not think that the resulting artificial energy shortage will be received well by anyone.

I did not address any aspects of the Smith et al., 2025 analysis other than the compliance obligation aspect. This analysis shows the investments from the NYCI program cannot achieve the annual emission reduction rate necessary to meet the 2050 goal but for the highest revenue scenario the rate could be achieved. This does not mean that NYCI investments will ensure that the 2030 goal can be met. The program hasn’t even been proposed. There won’t be any revenues available until 2026 and the programs need to be proposed, contracts let, and deployment started before there will be any emission reductions. Frankly, I doubt that there will be any meaningful emission reduction from NYCI investments by 2030. This finding emphasizes the need for a pause in implementation until the funding requirements for meaningful reductions are identified.

I expect to follow up with another post on this report later to address the main claim that the higher revenue scenario would “reduce household costs”.

Conclusion

The Smith et al., 2025 analysis proposes an allocation scheme for NYCI revenues. I did not address the specifics of their proposal. My interest was the acknowledgement of the Cullenward and Victor work that persuasively argues that the level of expenditures needed to implement the net-zero transition vastly exceeds the “funds that can be readily appropriated from market mechanisms”. The performance of NYSERDA investment of RGGI proceeds confirms that argument.

The biggest question is the appetite of New Yorkers to accept a $13 billion-dollar annual carbon tax whatever the investment benefits claimed. Governor Hochul will be running for re-election in 2026 so I believe the political machinations regarding costs will be the over-riding factor in the choice of the allowance ceiling price and the costs to consumers. Unacknowledged by most are the compliance obligations that could have massive unintended consequences. Stay tuned.