On February 15, 2024 Governor Hochul announced $200 million in utility bill relief for 8 million New Yorkers. The press release quoted her as saying “Energy affordability continues to be a top priority in my clean energy agenda and this utility bill credit is just one of many actions New York is taking to reduce costs for our most vulnerable New Yorkers.” This post shows how some of the numbers given can be used to put implementation costs for the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) into context.

I have followed the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 400 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

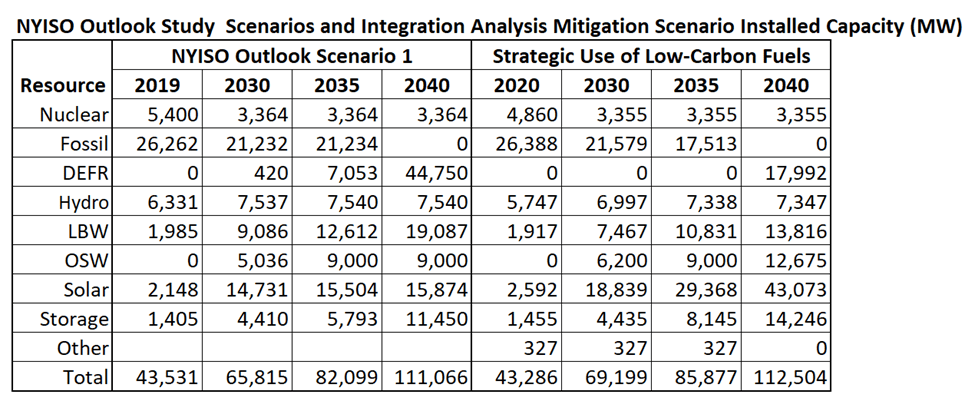

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. It includes an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% reduction by 2030 and a requirement that all electricity generated be “zero-emissions” by 2040. The Climate Action Council (CAC) is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlines how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” In brief, that plan is to electrify everything possible using zero-emissions electricity. The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to develop the Draft Scoping Plan outline of strategies. After a year-long review, the Scoping Plan was finalized at the end of 2022. In 2023 the Scoping Plan recommendations were supposed to be implemented through regulation, PSC orders, and legislation. Not surprisingly, the aspirational schedule of the Climate Act has proven to be more difficult to implement than planned and many aspects of the transition are falling behind. In addition, the magnitude of the necessary costs is coming into focus despite efforts to hide them. A political reckoning is inevitable in my opinion.

Press Release

This section quotes the press release and includes my comments.

The introduction outlines the rebate plan:

Governor Kathy Hochul today announced that the New York State Public Service Commission adopted a $200 million New York State energy bill credit to be administered by the large electric and gas utilities on behalf of their customers. The energy bill credit is a one-time credit using State-appropriated funds to provide energy bill relief to more than 8 million directly metered electric and gas customers. With today’s action, more than $1.4 billion has been or will be made available to New York consumers to help offset energy costs in 2024.

The rebate totals $200 million and gives a one-time credit to 8 million directly metered electric and gas customers. Ry Rivard in the February 16 edition of Politico Pro NY & NJ Energy notes that “The money, which will be spread across eight million electric and gas customers, amounts to roughly a one-time bill credit of about $24.”

Hochul provides the rationale for the rebate:

“Every New Yorker deserves affordable and clean energy, which is why I fought to secure additional funds to provide financial relief for hardworking families,” Governor Hochul said. “Energy affordability continues to be a top priority in my clean energy agenda and this utility bill credit is just one of many actions New York is taking to reduce costs for our most vulnerable New Yorkers.”

In Albany there are always working groups, advisory councils, and other committees set up to deflect blame and/or claim benefits. In this instance the Energy Affordability Policy working group, “a group of stakeholders that included the most prominent consumer advocacy groups in the state” made the recommendations. The press release states:

The program, proposed by the Energy Affordability Policy working group, provides that the $200 million appropriation included in the FY24 State Budget will be allocated to customer accounts through a one-time credit within roughly 45 days of the utilities receiving budget funds. This utility bill relief builds on several other key energy affordability programs administered by New York State, including $380 million in energy assistance program (EAP) funding for consumers through utilities, $360 million in Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) funding, $200 million in EmPower+ funding through the State Budget, over $200 million in ratepayer funding to provide access to energy efficiency and clean energy solutions for low-to -moderate income (LMI) New Yorkers through the Statewide LMI portfolio and NY Sun, and more than $70 million annually through the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP).

The Department of Public Service (DPS), in consultation with the Energy Affordability Policy working group, was tasked with designing a utility bill relief program related to the costs of utility affordability programs in recognition of energy commodity cost increases and the costs of utilities’ delivery rate increases. The working group considered multiple proposals over several months to effectuate the desired relief. The majority of the working group agreed to the staff proposal after several key modifications and recommended the PSC implement a one-time energy bill credit that would primarily benefit residential and small business electric and gas customers.

The Energy Affordability Policy working group is made up of leading consumer groups and advocates, municipalities, relevant state agencies, and utilities in New York.

Ry Rivard explains that the PSC was asked to divvy up the money in a few different ways:

New York City, for instance, urged the commission to provide different credits to gas customers depending on whether they used gas to heat their homes or just for cooking. And AARP, among others, argued the bill credits should be targeted to people who need the help most.

Ultimately, the PSC went with a simple, rough and ready way that gets money out the door quickly and just in time to help reduce winter heating bills: divide the money available by the number of customers.

A large section of the press release was devoted to congratulatory statements and descriptions of other ways the Hochul Administration wants to help:

PSC Chair Rory M. Christian said, “We applaud Governor Hochul for continuing to address the high cost of utility bills in New York State head on. While global commodity price volatility and utility delivery rate requests for increases, the Governor’s new and innovative energy affordability initiatives are coming at exactly the right time.”

Public Utility Law Project (PULP) Executive Director and Counsel Laurie Wheelock said, “PULP extends our sincere gratitude to Governor Hochul and the State Legislature for the allocation of a historic $200 million in the FY 2023-24 State Budget to address energy affordability. PULP and other stakeholders, including the Department of Public Service, Joint Utilities, and fellow consumer advocates, worked together to put forward a proposal that would provide relief to customers. The Commission’s decision today underscores a shared commitment to find ways to aid all New Yorkers, including our most vulnerable households, facing rising utility costs and volatile electric and natural gas prices. As we celebrate this milestone, PULP remains committed to identifying and advocating for additional measures to ensure energy is affordable in 2024 and beyond.”

In addition to the energy bill credit funds and EmPower+, New York State programs offer funding and technical assistance that can assist homeowners, renters, and businesses manage their energy needs. This includes:

Apply for HEAP: As of November 1, applications were being accepted for the Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) which can provide up to $976 to eligible homeowners and renters depending on income, household size and how they heat their home (e.g., family of four with a maximum monthly gross income of $5,838 can qualify). For more information visit NYS HEAP.

Energy Affordability Program/Low Income Bill Discount Program: This program provides income-eligible consumers with a discount on their monthly electric and/or gas bills, as well as other benefits, depending on the characteristics of the particular utility’s program. New Yorkers can be enrolled automatically if they receive benefits from a government assistance program. For more information, they should visit their utility website or links can be found at DPS Winter Preparedness.

Community-based Service Programs: Service organizations and local community agencies provide financial aid, counseling services and assistance with utility emergencies. New Yorkers can contact organizations like the American Red Cross (800-733-2767), Salvation Army (800-728-7825), and United Way (2-1-1 or 888-774-7633) to learn more.

Receive a customized list of energy-related assistance in the State: New York Energy Advisor can help income-eligible New Yorkers locate programs that help them spend less on energy and create healthier and more comfortable spaces. With New York Energy Advisor, consumers answer simple questions and get connected with energy-saving offers in New York State. Sponsored by NYSERDA and utilities, qualified New Yorkers can get help paying utility bills, receive special offers on heating assistance, and more.

EmPower+: Income-eligible households can receive a home energy assessment and no-cost energy efficiency upgrades through the EmPower+ program, administered by NYSERDA. Get more information about the program, including information on how to apply at https://www.nyserda.ny.gov/All-Programs/EmPower-New-York-Program.

Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP): Administered by New York State Homes and Community Renewal, WAP provides income-eligible households with no-cost weatherization services. Rental properties can also be served, though there are additional requirements for owners of rental properties. For more information on WAP, including how to apply, visit https://hcr.ny.gov/weatherization-applicants.

The press release ends with a bragging reference to the Climate Act. Not mentioned here is how the Climate Act initiative will affect consumer costs. It is the same oft-repeated drivel seen before so I will not comment here.

New York State’s Nation-Leading Climate Plan

New York State’s nation-leading climate agenda calls for an orderly and just transition that creates family-sustaining jobs, continues to foster a green economy across all sectors and ensures that at least 35 percent, with a goal of 40 percent, of the benefits of clean energy investments are directed to disadvantaged communities. Guided by some of the nation’s most aggressive climate and clean energy initiatives, New York is on a path to achieving a zero-emission electricity sector by 2040, including 70 percent renewable energy generation by 2030, and economywide carbon neutrality by mid-century. A cornerstone of this transition is New York’s unprecedented clean energy investments, including more than $40 billion in 64 large-scale renewable and transmission projects across the state, $6.8 billion to reduce building emissions, $3.3 billion to scale up solar, nearly $3 billion for clean transportation initiatives, and over $2 billion in NY Green Bank commitments. These and other investments are supporting more than 170,000 jobs in New York’s clean energy sector as of 2022 and over 3,000 percent growth in the distributed solar sector since 2011. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve air quality, New York also adopted zero-emission vehicle regulations, including requiring all new passenger cars and light-duty trucks sold in the State be zero emission by 2035. Partnerships are continuing to advance New York’s climate action with 400 registered and more than 100 certified Climate Smart Communities, nearly 500 Clean Energy Communities, and the State’s largest community air monitoring initiative in 10 disadvantaged communities across the State to help target air pollution and combat climate change.

Discussion

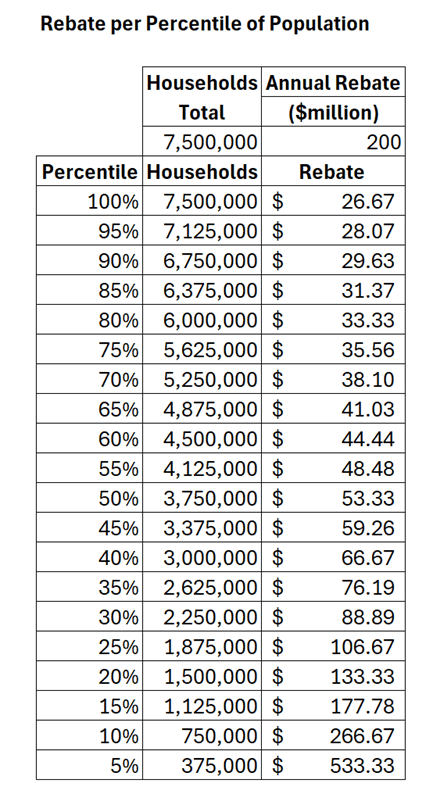

In this section I will put some context around these numbers: rebate totals $200 million and gives a one-time credit to 8 million directly metered electric and gas customers which “amounts to roughly a one-time bill credit of about $24.” In my opinion it is disappointing that this rebate apparently is being given to everyone and not limited to those who can least afford high energy costs. I calculated the rebate as function of the number of household percentiles. Using 7.5 million households as the state total and dividing by the $200 million rebate gives $26.67 per household. If only half the households are eligible for the rebate the $200 million is divided by 3,375,000 the rebate goes up to $53.33. The numbers quoted earlier are different simply because a different number of households was used.

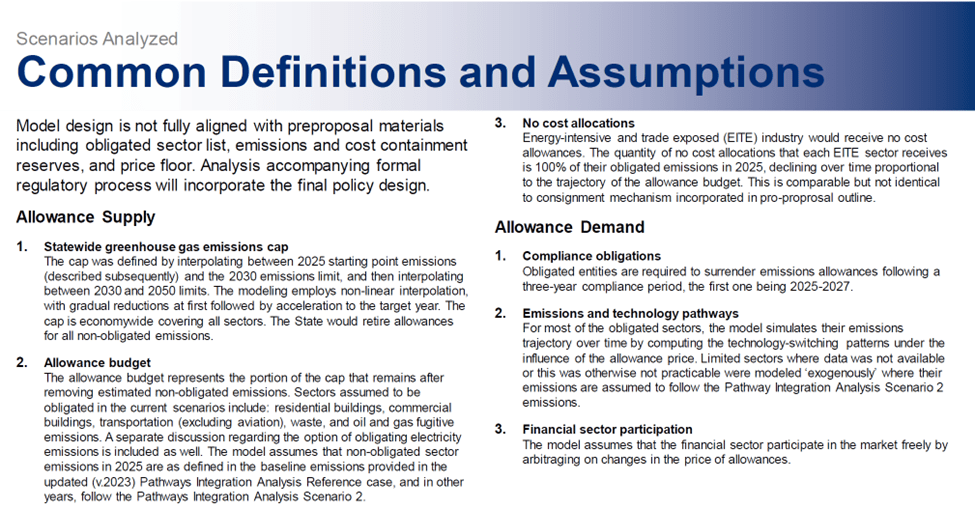

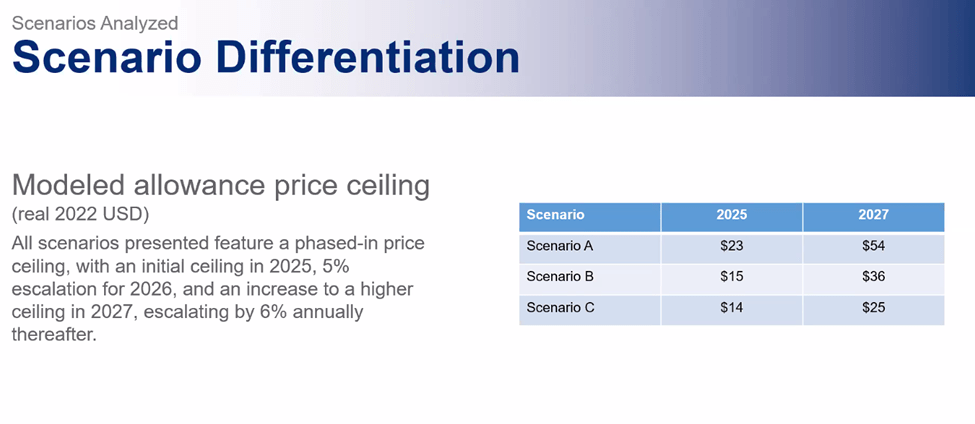

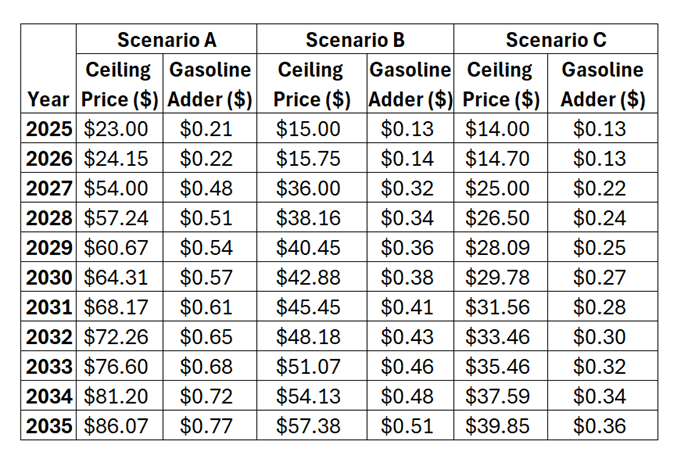

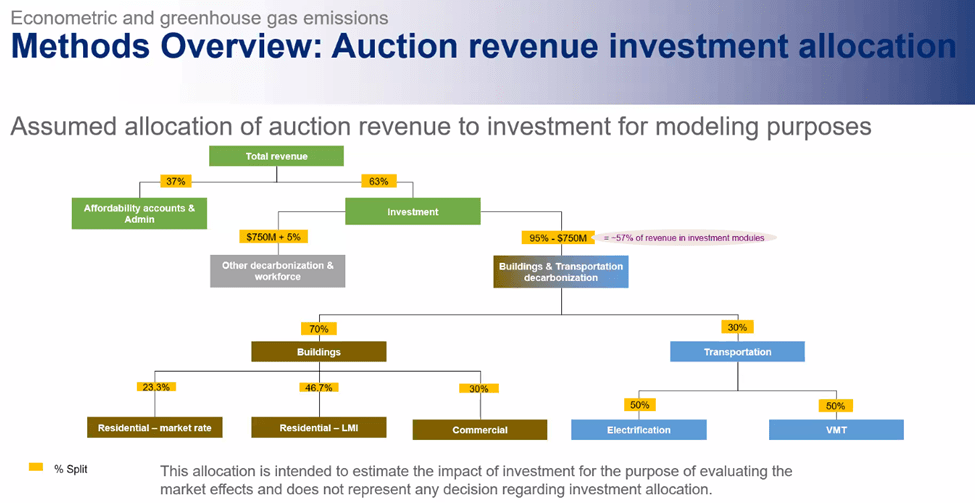

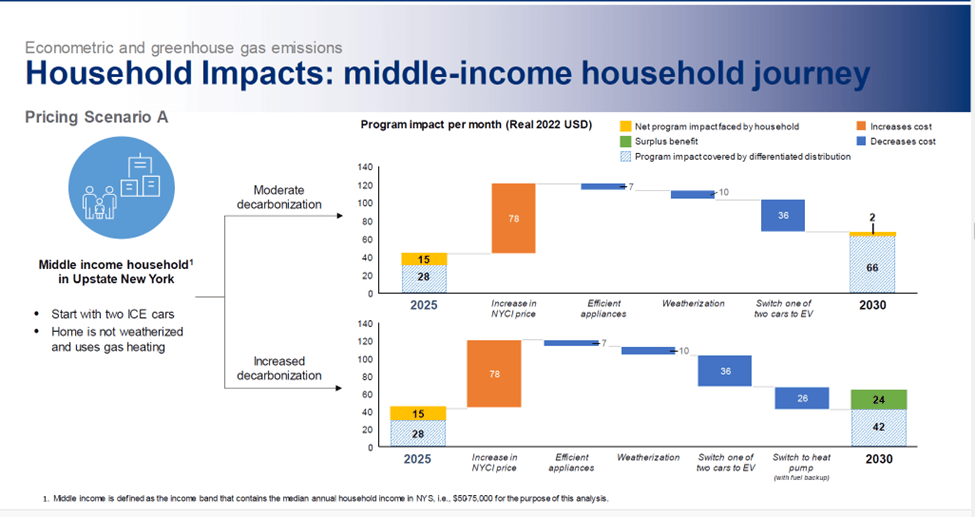

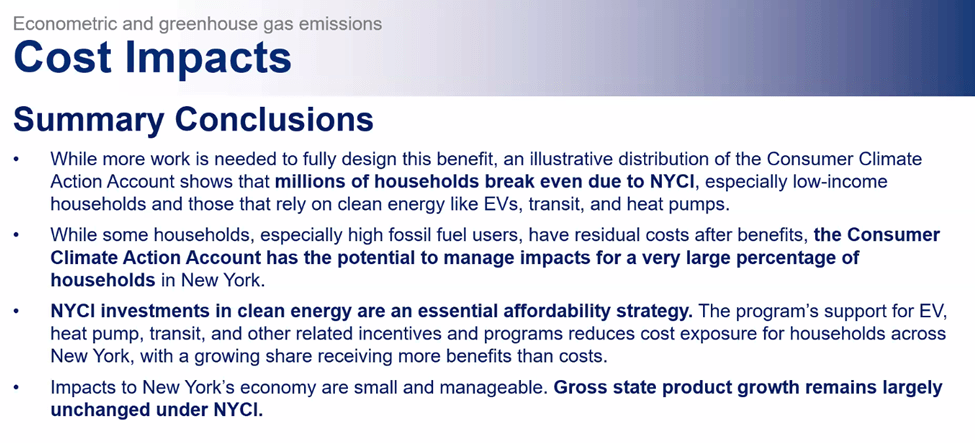

Last year legislation mandated that auction funds from the New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) program be allocated to the Consumer Climate Action Account (CCAA) as part of the overarching investment framework established for the New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) program A recent webinar on plans for NYCI noted that the first 37% of revenue generated by NYCI auctions is “set aside for the affordability accounts, the Consumer Climate Action Account, the industrial small business climate action account and administrative expenses.” The Consumer Climate Action Account itself is supposed to get 30% of the revenues. Recall that 2030 total revenue is “estimated to be between $6 and $12 billion per year” so the Consumer Climate Action Account should get between $3.3 and $1.5 billion in 2030.

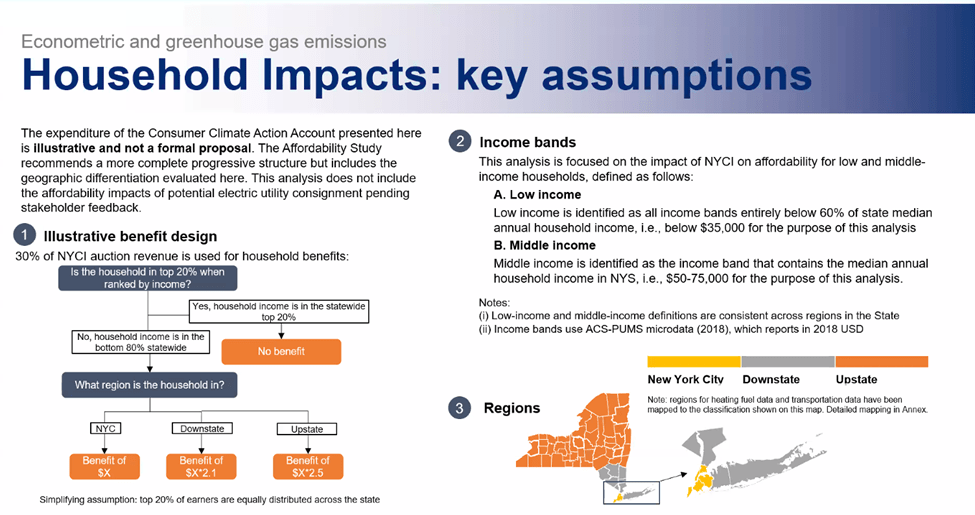

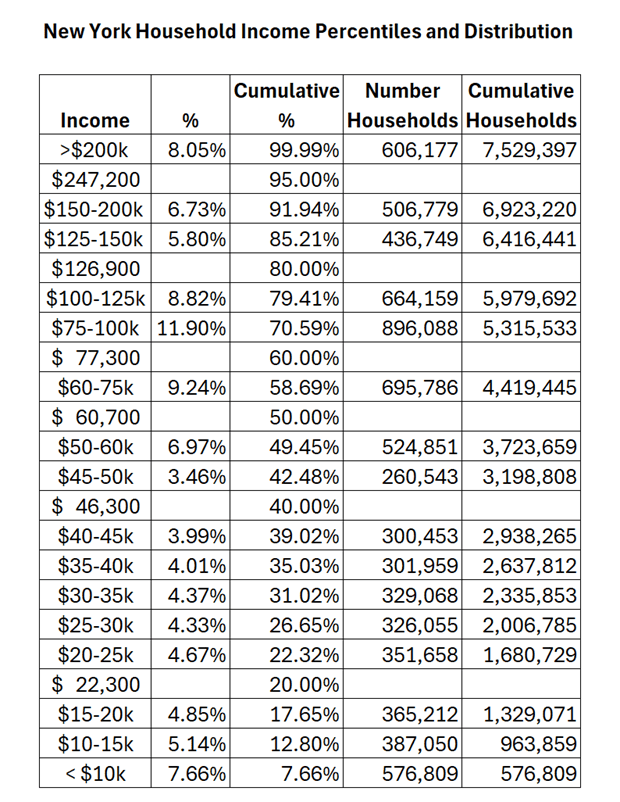

The amount of CCAA rebates to individual households is a function of the set-aside and the number of households eligible for the rebate. I previously found an overview of New York household income at Statistical Atlas that I used to estimate income percentiles and number of households at different levels in the following table. Note that the total number of households from this source is slightly different than what was used before. The NYCI webinar presentation stated that there will be no benefit for households in the top 20% which according to the table corresponds to an income exceeding $126,900. There are six million households under that threshold which means that around 1.5 million households in the top 20% of income will get no benefit. Low-income households are those below $35,000 and there are 2.3 million households in that category. There are 2.1 million households above $35,000 but below $75,000. Middle income is identified as the income band that contains the median annual household income in NYS, i.e., $50-75,000 for the purpose of the NYCI analysis. That leaves 1.6 million households with income between $75,000 and $126,900.

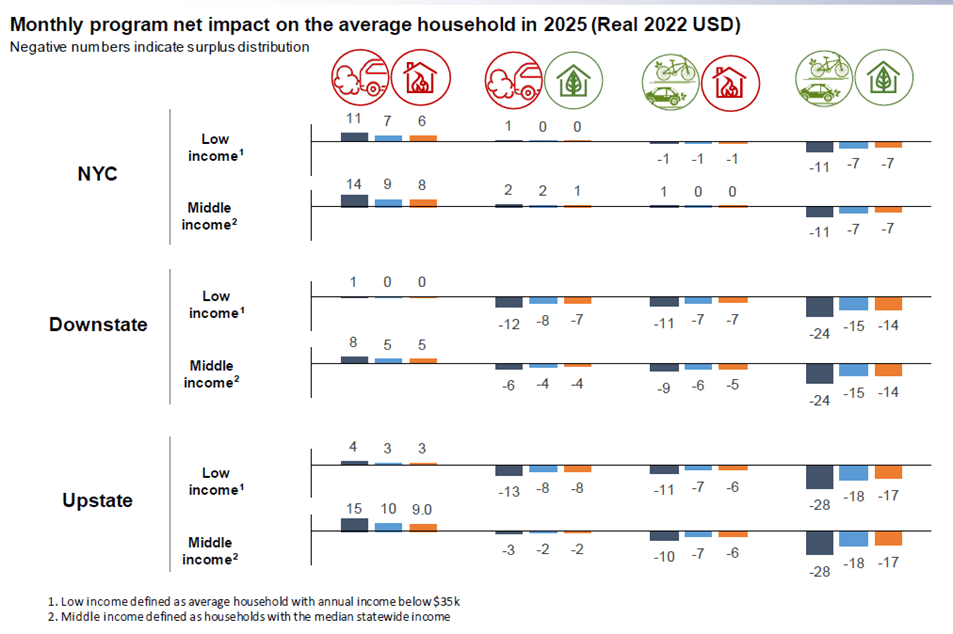

The following table lists the CCAA rebates for the four income categories described above. I assumed that the rebates would be assigned across the income categories included for the two NYCI revenue categories ($6 to $12 billion). If the auction revenues are distributed only to low-income households with incomes less than $35K, then each household will get between $774 and $1547 per year. At the other end of the range where every household with incomes less than the 80th percentile gets an equal share then the CCAA rebate will be between $300 and $600. I think it is more equitable to focus benefits on the lower brackets. The lower table apportions the rebates so that the upper bracket gets 20% while the lower two brackets each get 40%. In this example, rebates range from $225 to $619 per year.

Hochul’s press release noted “Energy affordability continues to be a top priority in my clean energy agenda and this utility bill credit is just one of many actions New York is taking to reduce costs for our most vulnerable New Yorkers.” This program is a $200 million appropriation coming from some never mentioned pot of money in the 2024 budget. This utility bill relief builds on several other key energy affordability programs administered by New York State: $380 million in energy assistance program (EAP); $360 million in Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) funding; $200 million in EmPower+ funding through the State Budget; over $200 million in ratepayer funding for energy efficiency and clean energy solutions for low-to -moderate income (LMI) New Yorkers; and more than $70 million annually through the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP).

The hypocrisy of this press release is astonishing. It claims a total of $1.41 billion for programs that help with energy affordability. Today energy affordability is affected by the energy policy of the Hochul Administration and in the future those costs will increase much more. The Administration has never quantified how these investments will affect global GHG emissions. My analysis has shown that while there is interannual variation, the five-year annual average increase in global GHG emissions has always been greater than 0.79% until the COVID year of 2020. I also found that New York’s share of global GHG emissions is 0.42% in 2019 so this means that global annual increases in GHG emissions are greater than New York’s total contribution to global emissions. Anything we do will be supplanted by emissions elsewhere in less than a year. In that context, it is appropriate to ask whether the Climate Act transition plan is appropriate because it is forcing over a billion dollars to help reduce the cost impacts of the transition. Eventually all this money must come out of the pockets of New Yorkers for no quantifiable benefit to global emissions.

Conclusion

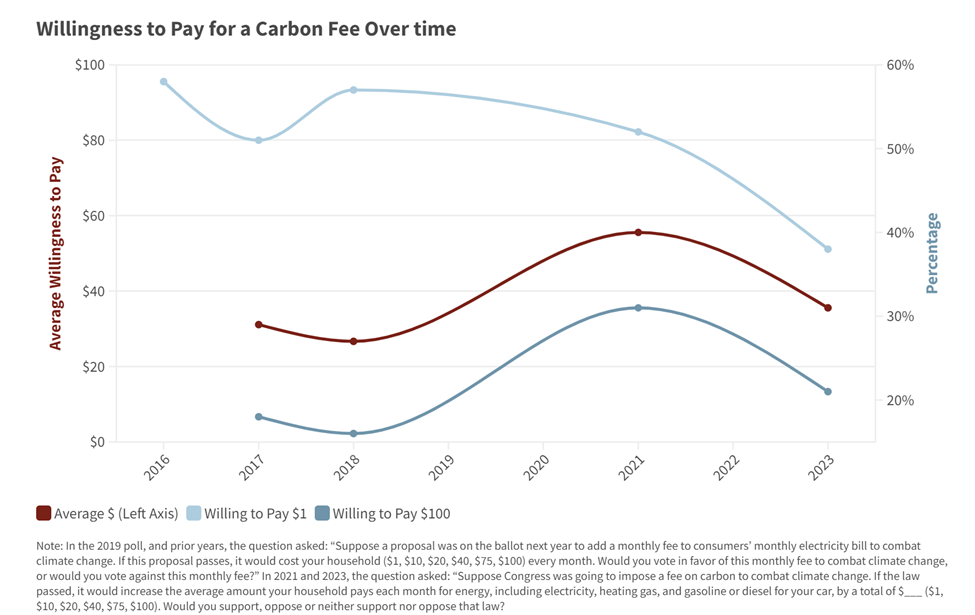

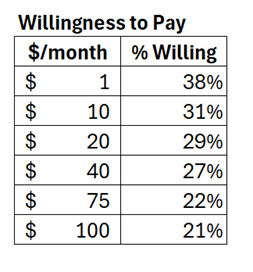

The Hochul Administration has never admitted how much households can expect to pay to implement the Climate Act net-zero transition plan. The plan is to electrify as much energy use as possible. That means we will be required to electrify home heating, cooking, and hot water as well as moving to electric vehicles. Recent electric rate cases have included double digit increases needed so support the Climate Act transition. I have no doubt that the costs of the transition for households will far exceed these rebates described in the press release. I urge all New Yorkers to demand an open and transparent accounting of the costs so we can all decide if we are willing to foot the enormous bills coming our way. There is no way the State can rebate its way to prevent those who can least afford the regressive increases in energy prices to not be adversely affected.