The goals for two proceedings associated with the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) are not clear. The Public Service Commission (PSC) Order on Implementation of the Climate Act (Case 22-M-0149) is supposed to “both track and assess the advancements made towards meeting the CLCPA mandates and provide policy guidance, as necessary, for the additional actions needed to help achieve the objectives of the Climate Act”. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) are implementing the New York Cap-and-Invest (NYCI) proposed by Governor Hochul which is a market-based program to raise revenues for the strategies necessary to meet the mandates of the Climate Act. The question for both programs is whether their goal is to address the Climate Act itself or the entirety of the effort needed to make the transition targets mandated by the Climate Act.

I have been following the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 300 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. I have devoted a lot of time to the Climate Act because I believe the ambitions for a zero-emissions economy embodied in the Climate Act outstrip available renewable technology such that the net-zero transition will do more harm than good. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Climate Act Background

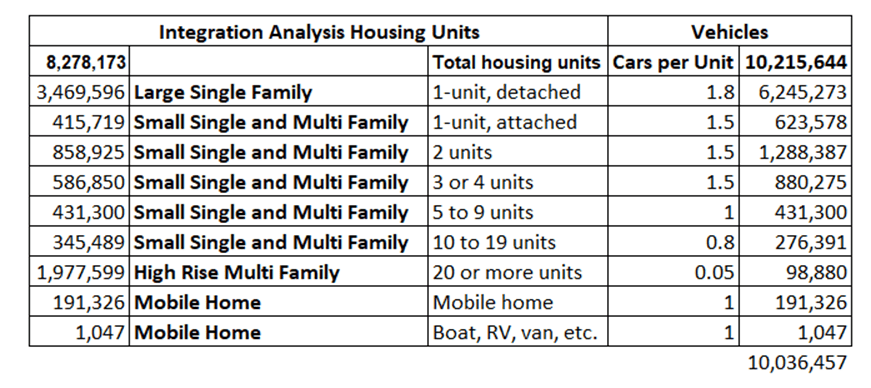

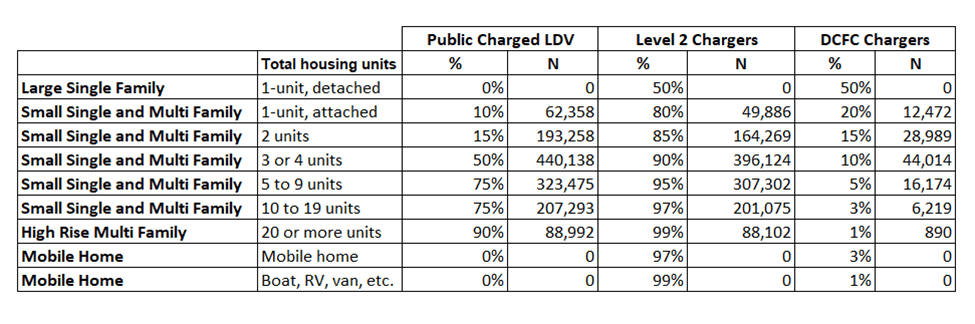

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050 and an interim 2030 reduction target of a 40% reduction by 2030. The Climate Action Council is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlines how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” In brief, that plan is to electrify everything possible and power the electric grid with zero-emissions generating resources. The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to write a Draft Scoping Plan. After a year-long review the Scoping Plan recommendations were finalized at the end of 2022. In 2023 the Scoping Plan recommendations are supposed to be implemented through regulation and legislation. This post addresses a couple of implementation components.

PSC Order on Implementation of the Climate Act

The order implementing this proceeding explains that:

The changes contemplated by the CLCPA are expected to profoundly transform the State’s regulatory landscape and impact every sector of the economy. The Public Service Commission (Commission) will play a critical role in these efforts as it continues to implement a variety of clean energy initiatives, including those related to the deployment of renewable energy resources to support the State’s transition to a zero emissions electric grid, energy efficiency, building electrification, and zero emission transportation.

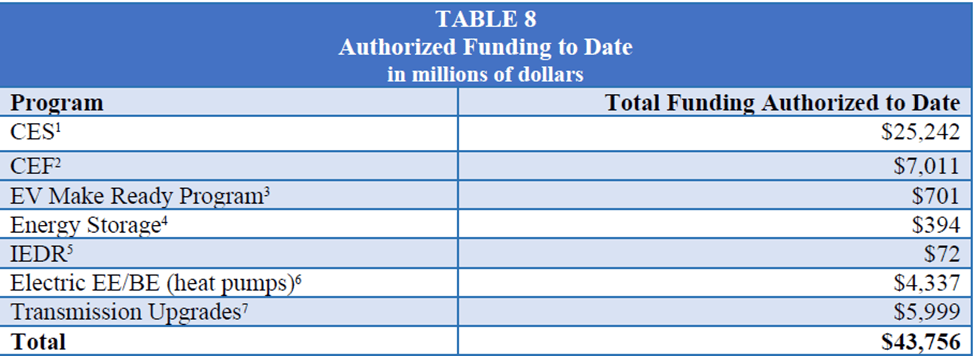

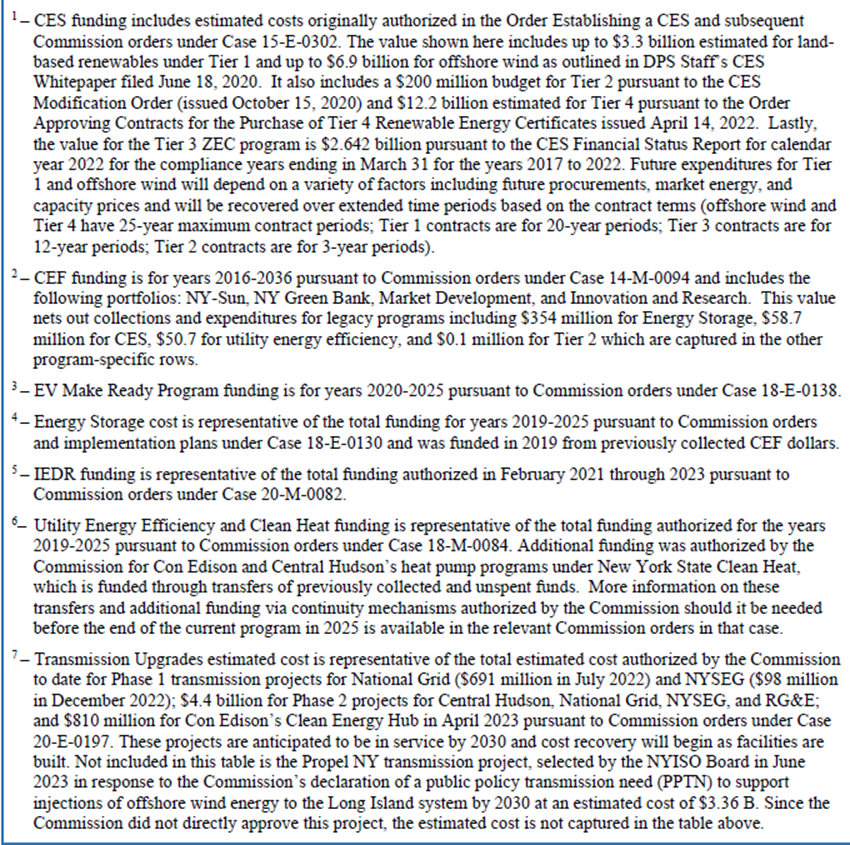

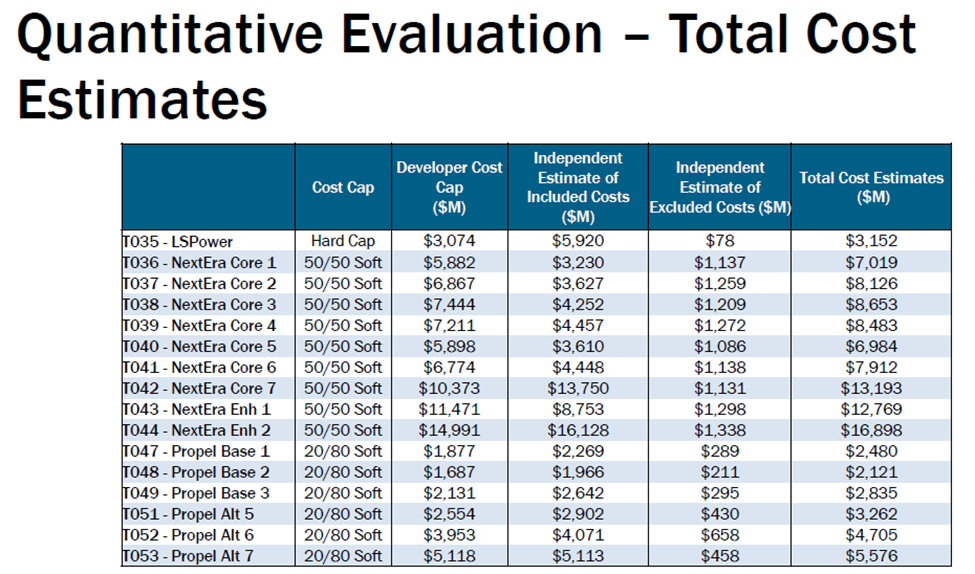

The Commission has already begun to implement the many objectives of the CLCPA through a number of existing proceedings. To date, the Commission has authorized the offshore wind solicitations necessary to achieve the CLCPA goal of procuring nine gigawatts (GW), funded programs to support the electrification of buildings’ heating load and the transportation industry, supported both large scale and distributed clean energy project development, funded programs to reduce natural gas and electricity usage in the State, and instituted a coordinated planning process to evaluate local transmission and distribution system needs to support the State’s full transition to renewable generation.

The Commission has quickly taken action related to items within its jurisdiction to help put the State on a path to meet the aggressive CLCPA targets. However, in consideration of the scope of the CLCPA and the extensive work necessary to achieve its mandates, continuous monitoring of the progress made will be crucial to ensure the State remains on track to achieve these objectives. In addition, there are existing policies that will need to be reviewed, and new policies that will need to be developed, to further the enablement of the CLCPA. This proceeding will be the forum for such policy development. By this Order, the Commission institutes this new proceeding to both track and assess the advancements made towards meeting the CLCPA mandates and provide policy guidance, as necessary, for the additional actions needed to help achieve the objectives of the CLCPA.

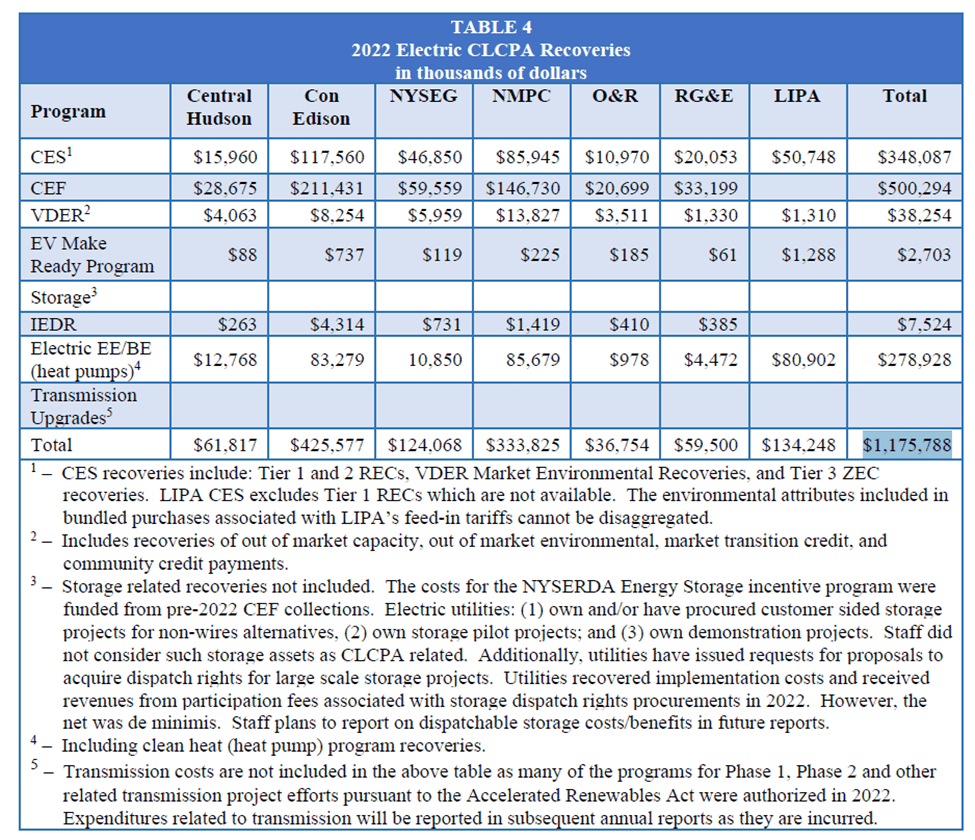

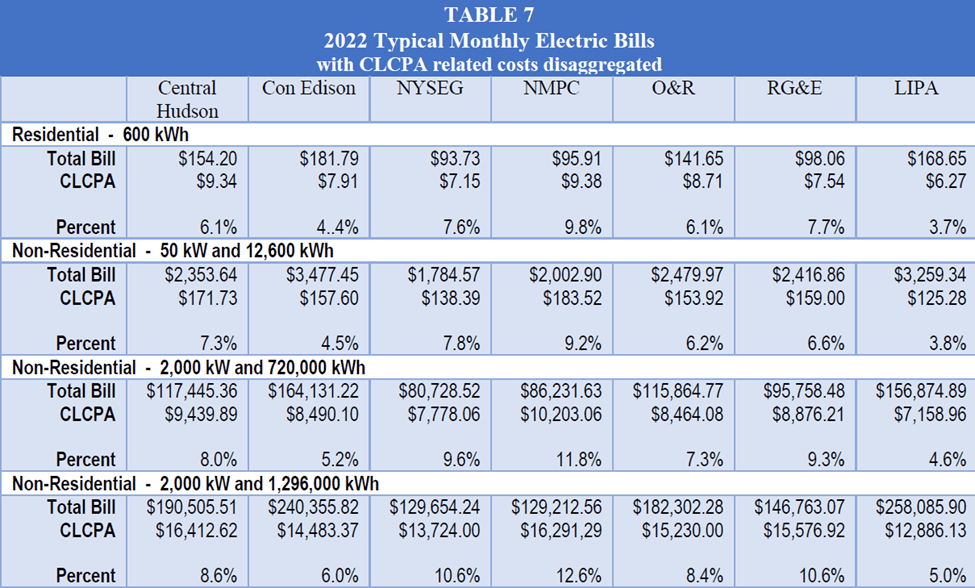

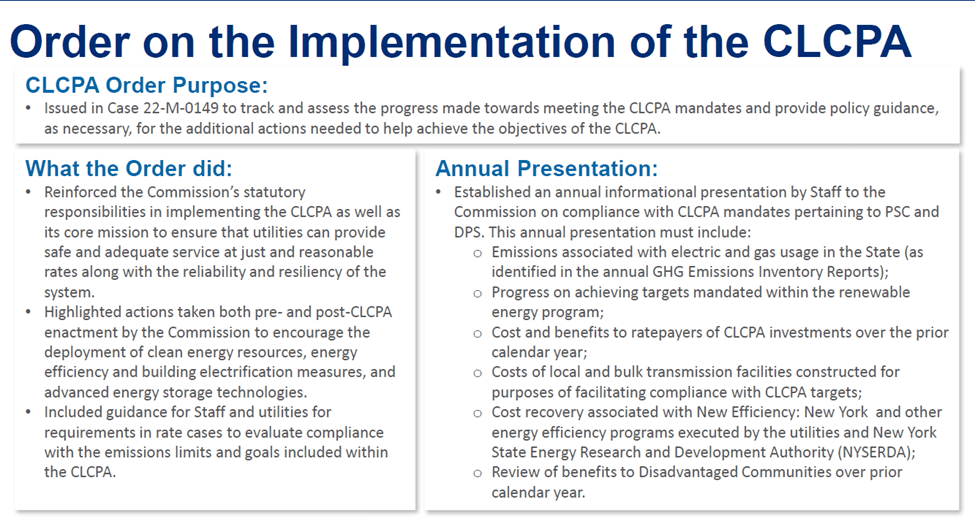

On July 20, 2023 the first annual informational report for this proceeding was released. The Power Point presentation summarizing the results includes the following slide describing the purpose, requirements, and goals for the annual report. It explains that the PSC has statutory responsibilities in implementing the Climate Act that must be consistent with its “core mission to ensure that utilities can provide safe and adequate service at just and reasonable rates along with the reliability and resiliency of the system.” My interpretation is that the PSC is required to address all actions, both pre-and post-Climate Act enactment by the Commission to achieve the mandates of the Act.

The report describes the information provided:

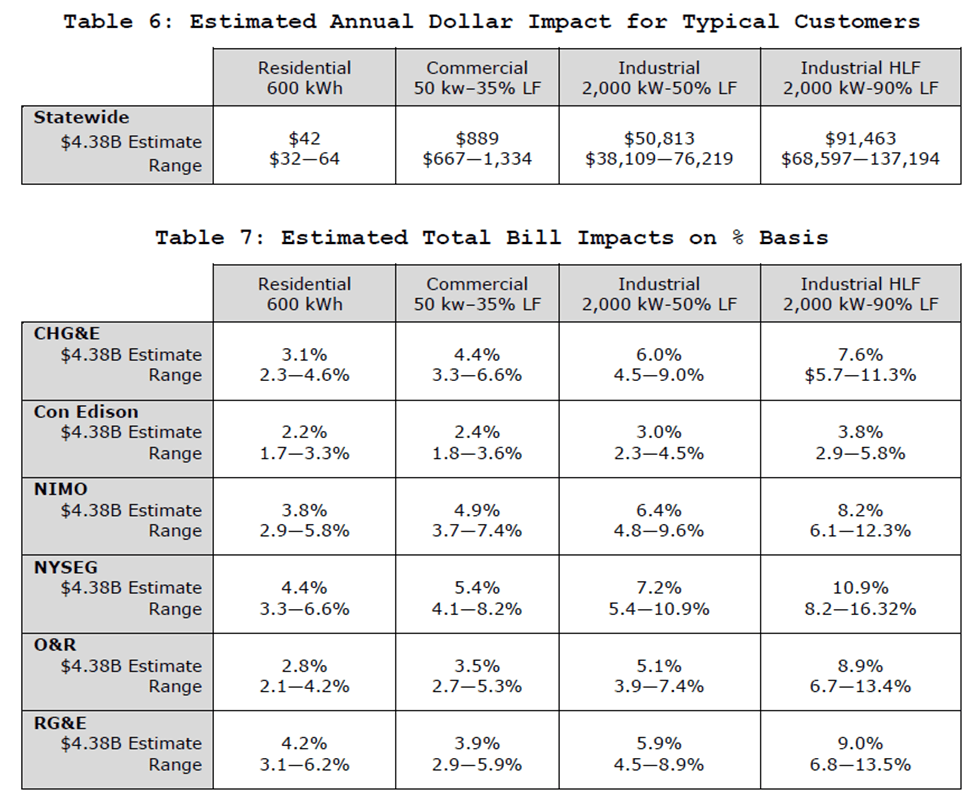

The cost recoveries, benefits, and other information reported here are mainly focused on the direct effects of CLCPA implementation. Notably, the estimates of total funding authorized by the Commission to date for various clean energy programs in some instances reflect actions that pre-date the enactment of the CLCPA. With respect to both pre- and post-CLCPA measures, this report focuses only the portion of those direct effects arising from programs over which the Commission has oversight authority and does not account for programs implemented by other state agencies that are funded from other sources (e.g., Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) funding). Examples of effects not captured here include property tax revenues to localities from newly developed renewable generation facilities, workforce development and job growth, and local air quality impacts, among others. It should also be noted that the benefits and costs of the measures discussed in this report do not accrue uniformly across stakeholders, and in some cases one stakeholder’s benefit is another’s cost. As such, this report generally describes a subset of benefits and costs related to the CLCPA and does so from the perspective of New York as a whole by using the Societal Cost Test. In instances where this report adopts a different perspective, it indicates what that perspective is. For those benefits that are difficult to quantify, this report includes qualitative descriptions of the nature, extent, and incidence of the benefit.

The issue I want to raise in this post relates to this description and the PSC core mission “to ensure that utilities can provide safe and adequate service at just and reasonable rates along with the reliability and resiliency of the system.” In particular, consideration of just and reasonable rates needs to consider the effect of other programs that directly impact rates. Although the Commission has no oversight authority for programs like RGGI and NYCI, the costs associated with those programs are passed through to ratepayers. Therefore, I believe that this report should include those costs and any other programs that directly affect ratepayer costs in its assessment.

New York Cap-and-Invest

In June 2023, DEC and NYSERDA hosted a series of webinars addressing NYCI implementation. The Cap-and-Invest Analysis Inputs and Methods webinar (Inputs and Methods Webinar Presentation and View Session Recording) on June 20, 2023 described proposed policy modeling. In order to evaluate the effects of different policy options, this kind of modeling analysis forecasts future conditions for a baseline or “business-as-usual” case, makes projections for different policy options, and then the results are compared relative to the baseline case.

The proposed modeling approach uses a unique approach. The Scoping Plan modeling used a reference case that included “already implemented” programs instead of the usual practice of a “business-as-usual” base case. The NYCI Cap-and-Invest Analysis Inputs and Methods webinar proposed to use the same framework. Starting with the reference case developed for the Scoping Plan, the NYCI modeling proposal will add policies enacted since then.

It is more appropriate to compare the policy cases to a base case that excludes all programs intended to reduce GHG emissions. Putting the pre-Climate Act programs and costs in the reference case means that the cost forecasts will not include all the measures necessary to meet the Climate Act mandates. One of the goals of NYCI is to “minimize potential consumer costs while supporting critical investments” but the proposed approach will only consider a subset of the total costs necessary to meet the Climate Act mandates.

Discussion

The question for both proceedings is whether the goal is to consider all the costs and benefits of the Climate Act or some sub-set. The Hochul Administration has never released its estimate of the total costs to meet any of the Climate Act targets. Instead of providing the cost and benefit components themselves only net numbers are provided to support the misleading and inaccurate party line statement that the costs of inaction are more than the costs of action. In order to make that statement the Administration used the reference case approach that hides the total implementation costs.

There are implications for these two proceedings. In order to provide the total costs, both should cover as many programs as possible. The PSC has statutory limits on its Climate Act Implementation analysis that precludes many aspects of the transition but I believe that they should incorporate the costs of Climate Act-related expenditures that get incorporated into ratepayer assessments even if they are not in a rate case proceeding. There was one relevant item not addressed in the PSC Climate Act Implementation Report. New York Public Service Law § 66-p. “Establishment of a renewable energy program” has safety valve conditions for affordability and reliability that are directly related to the PSC core mission “to ensure that utilities can provide safe and adequate service at just and reasonable rates along with the reliability and resiliency of the system.” § 66-p (4) states: “The commission may temporarily suspend or modify the obligations under such program provided that the commission, after conducting a hearing as provided in section twenty of this chapter, makes a finding that the program impedes the provision of safe and adequate electric service; the program is likely to impair existing obligations and agreements; and/or that there is a significant increase in arrears or service disconnections that the commission determines is related to the program”. I think that this mandate calls for including ratepayer costs that are not related to a rate case proceeding.

With respect to NYCI the question is what is the expectation for the revenues. The revenues needed to make the necessary changes to the energy system are not related to the legislation or regulation that drives the initiative. Therefore, the proposed modeling should evaluate the policy scenarios against a business-as-usual base case that excludes any program that exists to reduce GHG emissions. Furthermore, the proposed approach will not be able to provide an estimate of necessary revenues to meet the Climate Act mandates because it excludes already implemented policies and their associated costs.

Conclusion

The goals for these two programs should be clarified. I believe that I am not the only resident of New York that wants to know the all-in costs necessary to meet the Climate Act mandates. In order to provide those numbers both proceedings should address as many program costs as possible for the effort needed to make the transition targets mandated by the Climate Act.

I intend to evaluate the reported costs in the PSC Climate Act Implementation Analysis relative to the NYCI modeling proposal included programs. At this point I can only say the NYCI approach will be mis-leading for the revenue needs of the Climate Act transition costs but cannot estimate the magnitude of the error. Arbitrarily eliminating some costs is nothing more than a politically expedient ploy to downplay the total costs of the Climate Act.