Manhattan Contrarian Francis Menton’s recent article on electric truck deployment prompted Rich Ellenbogen to write an email to his distribution list that deserves a wider distribution. I have collaborated with both gentlemen because we all agree that the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (Climate Act) net-zero transition mandates are bound to fail simply because the ambition is too great. Nowhere is this more evident than the magical thinking associated with heavy-duty trucks.

Ellenbogen is the President [BIO] Allied Converters and frequently copies me on emails that address various issues associated with the Climate Act. I have published other articles by Ellenbogen including a description of his keynote address to the Business Council of New York 2023 Renewable Energy Conference Energy titled: “Energy on Demand as the Life Blood of Business and Entrepreneurship in the State -video here: Why NY State Must Rethink Its Energy Plan and Ten Suggestions to Help Fix the Problems” and another video presentation he developed describing problems with Climate Act implementation. He comes to the table as an engineer who truly cares about the environment but has practical experience that forces him to conclude that New York’s plans simply will not work.

Menton on Electric Trucks

Menton’s article makes the point that so far the impossible mandates of the Climate Act have all been so far in the future that reality has not been evident. He points out that:

In 2021 Governor Hochul sought to do the Climate Act one better by adopting a regulation called the Advanced Clean Truck Rule. This Rule requires a certain percentage of heavy duty trucks sold in New York to be “zero emissions,” i.e., all-electric. It so happens that New York copied this Rule and its percentages from California. For the 2025 model year, now under way, the relevant percentage is 7%.

He continues:

All-electric heavy duty trucks? Did anyone think this one through? Clearly not. The New York Post today reports that two upstate legislators of the Democratic Party have now introduced legislation to postpone the electric heavy-duty truck mandate until 2027. The legislators are Jeremy Coney Cooney of Rochester and Donna Lupardo of Binghamton. The two call the mandate “nearly impossible for the trucking industry to comply with.” Here is one among several noted problems: “The legislators noted that an average diesel truck can be refilled in about 10 minutes and can drive for about 2,000 miles. By comparison, an electric, zero-emission heavy-duty truck takes approximately 10 hours to charge and can run for about 500 miles. . . . “Battery charging times are . . . a challenge and will remain so until new technology emerges and is commercialized,” [Lupardo] said.

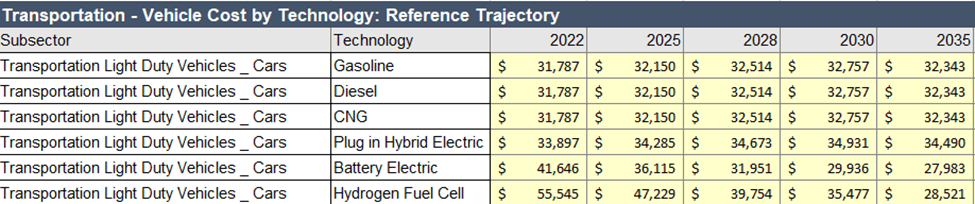

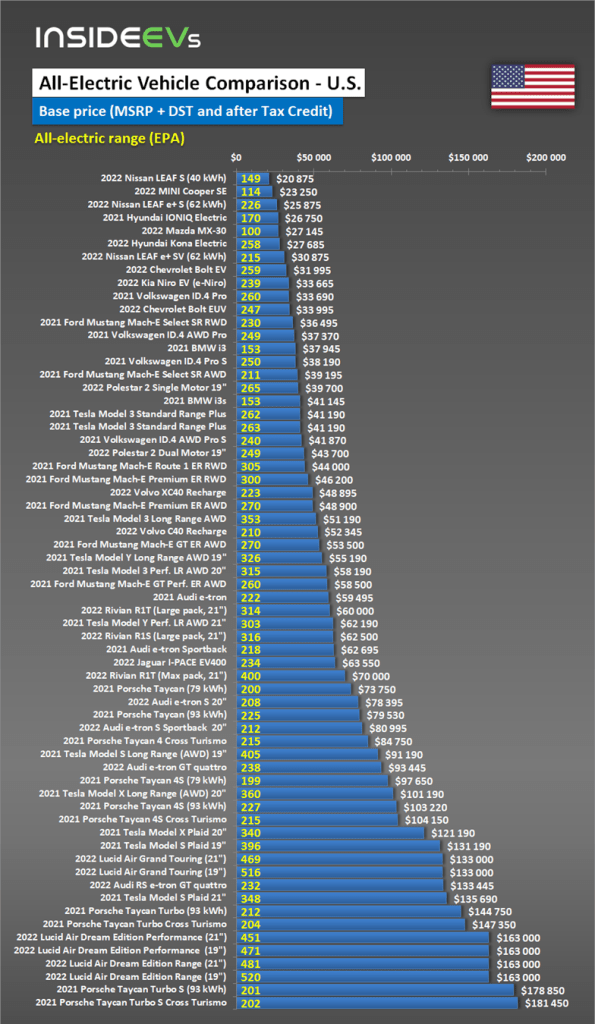

Menton argues that there is no way that these issues can be resolved in a couple of years. There is no way the battery challenges s are going to be resolved that soon. Throw in lack of charging infrastructure and costs (a fully-electric heavy-duty truck can be as much as triple that of a diesel competitor with comparable load capacity) and this is clearly unworkable. He also describes the difficulties trying to enforce a mandate on electric vehicle sales quotas. Despite the wails and gnashing of the teeth of the environmental advocates, Menton concludes that reality will win and this mandate will have to eventually be rescinded. I recommend the entire article for additional facts and context.

Ellenbogen Trucking Challenges

The following is Ellenbogen’s lightly edited email.

The electric truck situation is even more complex than Francis mentions and more unworkable. It’s more than the fact that the truck would cost three times as much as the Post clip said. Physics and energy math are getting in their way again. The truck would be so heavy that it couldn’t carry nearly the same amount of freight. It is apparent that whoever wrote the truck rules knew nothing about EV’s, long haul trucking, or Federal highway rules. They just didn’t like diesel fuel so they said, “Let’s make them electric” without thinking about what that would entail. Also, the following statement about comparable load capacity defies physics: “On the cost front, it the Post reports that the price of a fully-electric heavy-duty truck can be as much as triple that of a diesel competitor with comparable load capacity.”

We load large trucks several times per week at my factory and we must be very conscious of Gross Vehicle Weight. In the US, for an 18-wheeler with 5 axles, that is 80,000 pounds max or about 16,000 pounds per axle. Of those 80,000 pounds, about 35,000 pounds is the tractor and trailer including about 4000 pounds of fuel when fully loaded. We can safely load a truck with about 43,500 pounds of freight and stay below the weight limit without worrying about the fuel weight. We also must be careful to balance the load so that the weight is evenly distributed. If a trucker hits a weigh scale and there is too much weight on one axle or if the truck is overweight, they will be subject to fines in the thousands of dollars.

My Tesla X weighs 5400 pounds and can travel about 300 miles with a 100 KWh battery. A 100 KWh battery can weigh about 675 Kg or about 1500 pounds. If 1500 pounds of Lithium batteries can store enough energy to move 5400 pounds for 300 miles and energy used is proportional to distance and mass, then assuming the same velocity it would take almost fifteen times as much storage to move 80,000 pounds 300 miles, or about 22,500 pounds of batteries, 18,500 pounds more than the weight of the diesel fuel.

If we subtract 18,500 pounds from the 43,500 pounds of freight to meet Federal Highway Laws, no truck could carry more than 25,000 pounds of freight for 300 miles at a time so it would need almost two EV truck trips for one diesel truck trip. As diesel engines are about 43% energy efficient and EV’s are about 75% energy efficient, it would take 15% more energy to move the same amount of freight using an EV than with a diesel truck. It would also take two times as much labor to just move the freight within a very small radius. We ship truckloads across the country, and they will get there in three or four days. Hours of Service regulations require them to drive no more than 11 hours within a 14-hour window. They must take a mandatory 30-minute break after eight hours of driving. The EV truck couldn’t even make a round trip to Syracuse from my factory just north of New York City without stopping for charging. Diesel truck operations are limited by Federal regulations whereas electric trucks can only drive 4 – 5 hours before charging. As a result, about 4 hours of the 14 hours would be lost charging and the truck would lose at least 60 miles of range per day, or about 10% best case. Also, to charge a 1500 KWh battery pack in four hours would require the capacity of four to five Tesla chargers.

An enormous amount of the energy would be expended just moving the batteries, not the freight. It will use about 15% more energy per pound of freight, which is absolutely not “green” and it will use at least six times the amount of labor if you figure in charging stops. If you figure in generation losses if the energy is fossil fuel based, then you can at least double the energy use of the electric truck and the 15% becomes 100% more energy per pound of freight.

UPS has ordered several electric trucks but they aren’t doing long hauling with those and their freight is less dense so they might be able to stay below the 25,000 pound limit so it may work for them. For large, long-haul trucks, it will be logistically impossible. Sea containers can weigh 44,000 pounds. There isn’t a physical way to build an electric truck that could legally haul them to or from a pier.

We’re shipping 80,000 pounds of freight to Philadelphia next Tuesday on two trucks. The total fright cost is about $1800 or about 2.25 cents per pound. With electric trucks, the freight costs would be substantially higher. Just the fact that it would take twice the number of loads to move the same amount of freight would double the price but then you must figure in that the truck owner is amortizing three times the cost of the equipment and lost labor during charging, so the cost would likely triple or more.

Almost everything moves by a long-haul truck. If you want to see inflation, add that to the cost of every delivery if you could even find enough truck drivers to logistically drive all the extra loads that would be required. The entire idea is unworkable. It sounds like another not well thought out “only a matter of political will plan” from New York State and California.

Caiazza Conclusion

Menton and Ellenbogen describe insurmountable issues with the heavy-duty truck mandates. There is no way that the Climate Act heavy duty truck mandates can be achieved on schedule and probably not ever. This is another reason to pause the Climate Act implementation and rethink the ambition and schedule of all the mandates. Until the feasibility of each requirement has been proven it is utter folly to throw more money at these magical dreams.