On February 26, 2026 the Hochul Administration “leaked” a New York Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) memo that said that “full compliance with New York’s 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act could cost upstate households more than $4,000 a year – on top of what they are already paying today”. On March 5, 2026, a group of 29 New York Democratic state senators responded with a letter (“Democratic Letter”) to Governor Hochul saying they “categorically oppose any effort to roll back New York’s nation leading climate law” and urging Hochul to “stand strong in the face of misinformation” about affordability. The letter insists that any pushback on the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) amounts to “climate denial” and that only their “bold” agenda will save New Yorkers money, clean the air, and protect a livable climate for our grandchildren. That framing gets the politics right, but the facts are wrong.

I am convinced that implementation of the Climate Act net-zero mandates will do more harm than good if the future electric system relies only on wind, solar, and energy storage because of reliability and affordability risks. I have followed the Climate Act since it was first proposed, submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan, and have written over 600 articles about New York’s net-zero transition. The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other organization I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Overview

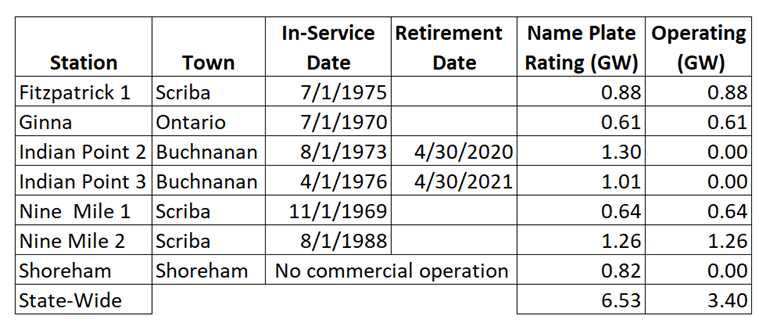

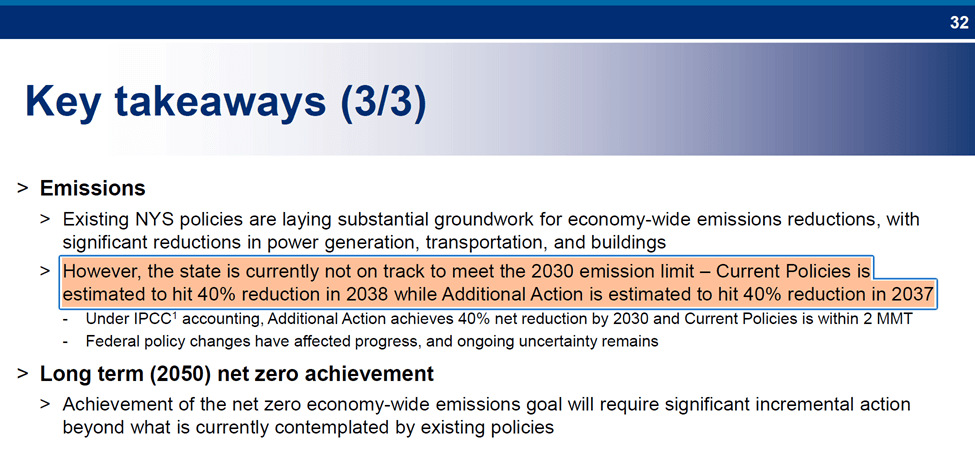

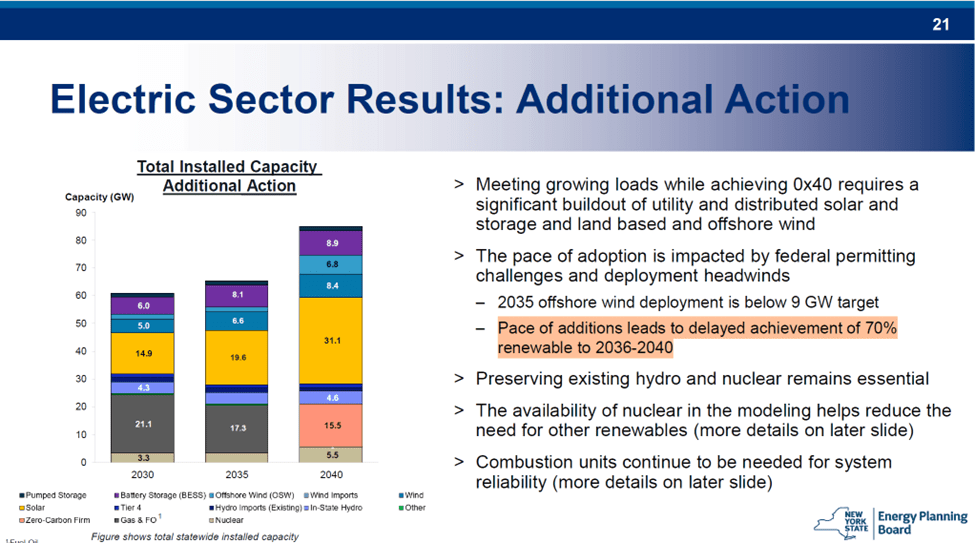

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction in GHG emissions and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. It includes an interim reduction target of a 40% GHG reduction by 2030. Two targets address the electric sector: 70% of the electricity must come from renewable energy by 2030 and all electricity must be generated by “zero-emissions” resources by 2040. The Climate Action Council (CAC) was responsible for approving the Scoping Plan prepared by New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) that outlined how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” NYSERDA also prepared the recent State Energy Plan that was approved by Energy Planning Board (EPB). Both the CAC and the EPB were composed of political appointees .

I am not a climate denier. The climate is always changing, and greenhouse gases affect climate, but the authors of the Democratic Letter do not acknowledge that climate uncertainty, natural variability, or observational constraints call for a realistic response. . I spent my 50-year career as an air pollution meteorologist working with real emissions, real regulations, and real power plants. The most disappointing aspect of the letter is that there is no recognition that as Dr. Matthew Wielcki has said “energy is not merely an input to the economy, but the foundation of human flourishing”. The question before New York is not whether climate change exists, but whether the package of mandates in the Climate Act is feasible, affordable, and effective. When it comes to those practical issues, the facts don’t sit well with the people throwing around the “denier” accusation.

Costs

Start with costs. When the Climate Act was passed, there was no honest, front‑end feasibility and cost analysis. Only after the targets were locked into law did agencies begin publishing scenarios showing the scale of spending required. Those scenarios all assume massive expansion of the electric grid, rapid electrification of heating and transportation, and large‑scale deployment of wind, solar, and batteries. None of this comes free. We are already seeing rising bills, growing arrears, and households struggling with basic energy costs, even before the most aggressive requirements take hold.

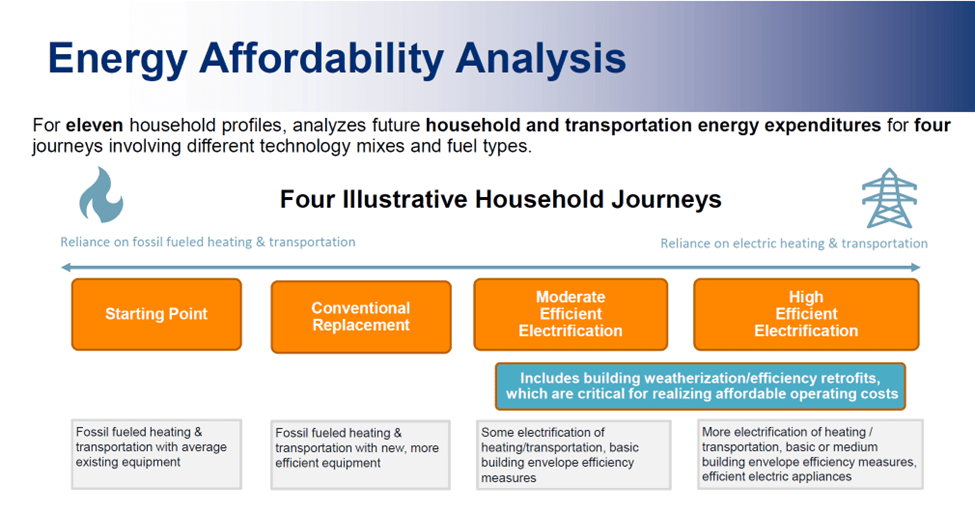

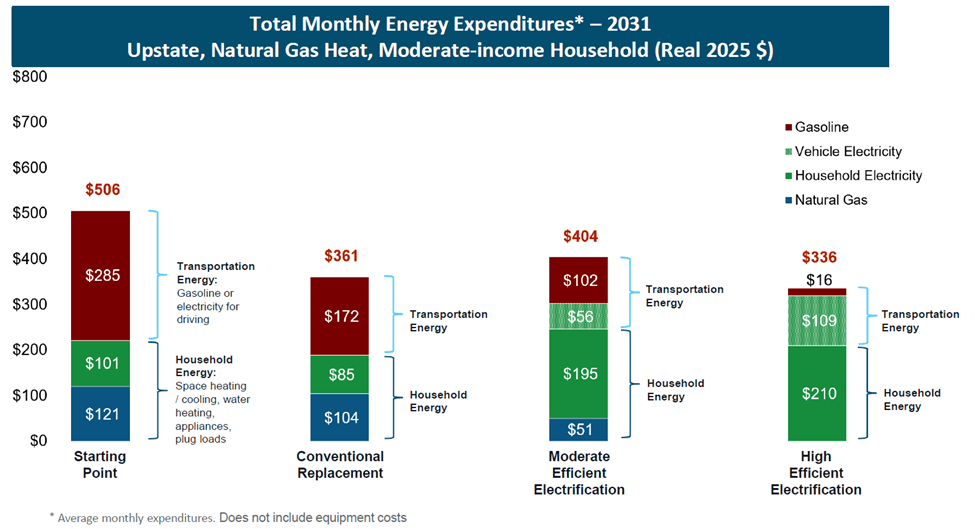

These lawmakers do not understand that NYSERDA’s cost estimates for the Climate Act Scoping Plan and the State Energy Plan are built on modeling choices that systematically understate the burden on New Yorkers: they embed Climate Act programs inside opaque “system” totals, use a “No Action” baseline that already includes other greenhouse‑gas policies, and present small percentage changes instead of the several‑hundred‑dollar‑per‑month increases that households will actually face.

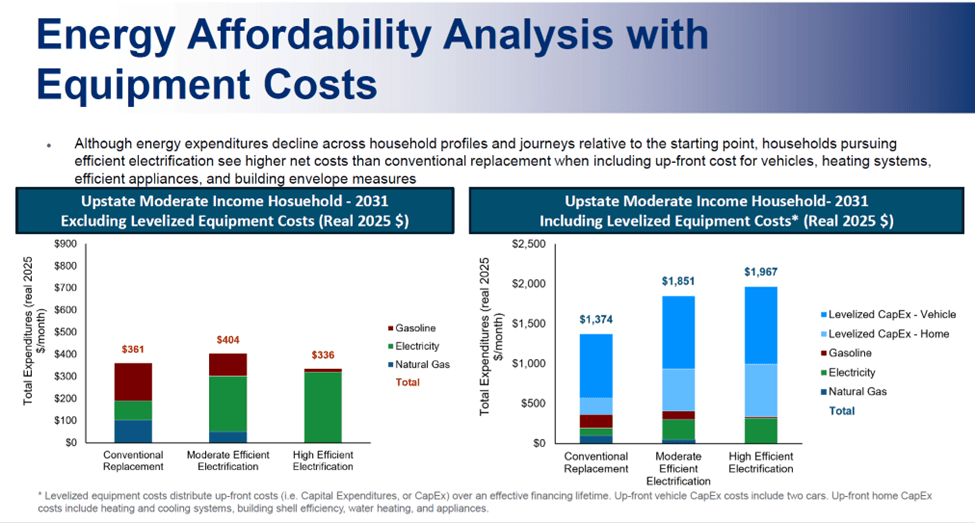

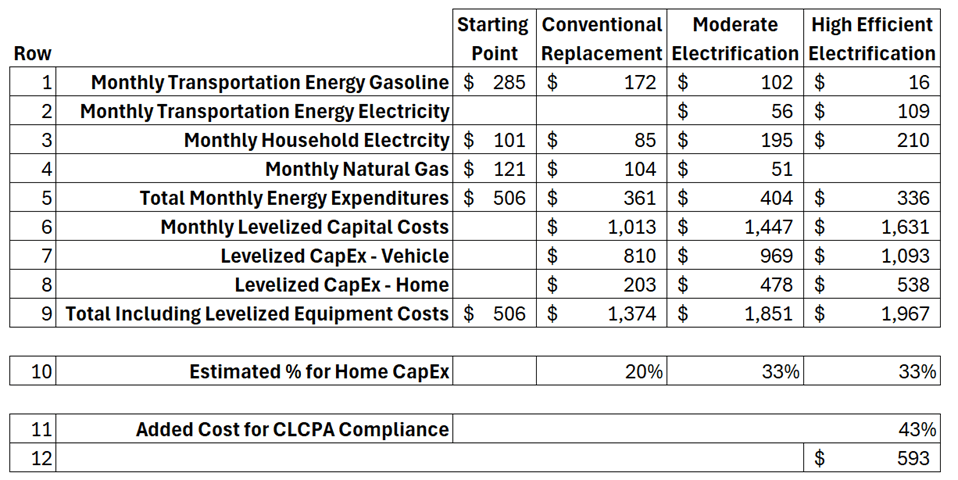

For example, the NYSERDA memo notes “absent changes, by 2031” that “Upstate oil and natural gas households would see costs in excess of $4,000 a year”. I believe that these costs are underestimated. Using State Energy Plan December 2025 data I determined costs to buy the equipment to meet the Climate Act household mandates for an Upstate New York moderate income household that uses natural gas for heat. NYSERDA’s Affordability Analysis Overview Fact Sheet claims that the use of new, efficient equipment can cut energy spending by $100 to over $300 per month, but those estimates do not include the costs of equipment. When equipment costs are included, the difference in monthly energy costs and levelized equipment costs between replacement with conventional equipment and electrification equipment consistent with Climate Act goals is $594 a month or $7,200 per year. For the only scenario where NYSERDA included equipment costs sum of those costs and those in the NYSERDA memo total compliance costs are $11,200 a year.

If these policies truly “saved New Yorkers money,” we would not need to hide behind slogans and carefully worded “average household savings” claims that depend on subsidies and optimistic modeling assumptions. We would see transparent accounting of rate impacts, program costs, and who pays when things go wrong. Instead, we get talking points and attacks on anyone who asks for a balance sheet.

Pollution

The pollution story is similarly oversold. New York dramatically cleaned up its air decades ago. We now live in one of the cleanest air basins in the country by traditional criteria pollutants. Additional greenhouse gas reductions here may be desirable, but they do not magically translate into big local health improvements when we are already near the floor. On climate itself, New York’s emissions are a tiny fraction of the global total. Even if we somehow hit every target in the Climate Act on time, the effect on global temperature would be too small to measure.

That does not mean “do nothing.” It does mean we should stop pretending that blowing up our energy system on an unrealistic timeline is a gift to the world’s climate and will have sufficient societal co-benefits to offset the actual costs. New York can and should reduce emissions, but it must do so in ways that maintain reliability, preserve affordability, and respect the limits of what one state can accomplish.

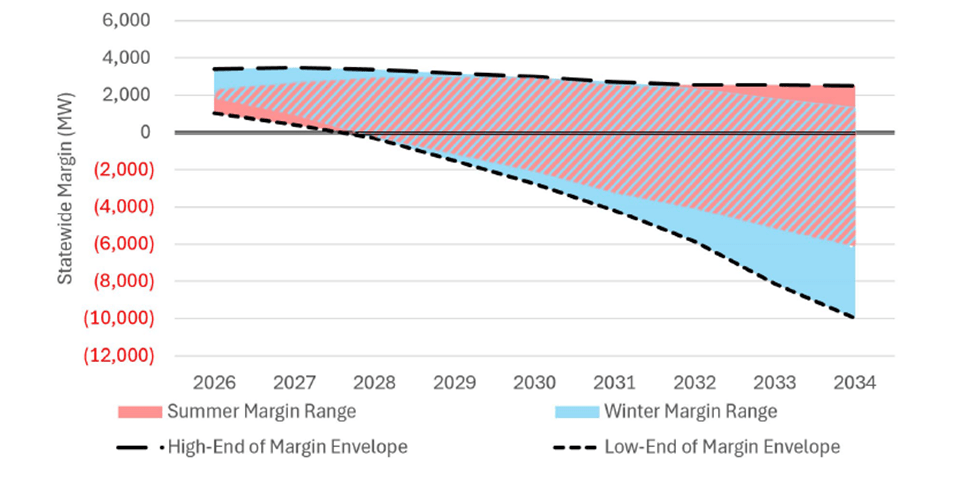

Reliability

The biggest gap in the “bold policy” rhetoric is reliability. A livable climate for our children and grandchildren does not include routine blackouts, shuttered industries, and a grid that fails under stress. Yet the very same politicians who decry “denial” are remarkably casual about the technical challenge of running a winter‑peaking system in a cold climate on weather‑dependent generation backed by storage that does not yet exist at the necessary scale.

Many lawmakers do not understand the electric system and advocate for a flexible electric grid. They don’t understand that the electric system must be built around reliability during peak demand because that is when it is needed the most. That is why utilities must invest so much in preparation for peak times. While that adds to costs it is also why ratepayers are assured power is always available.

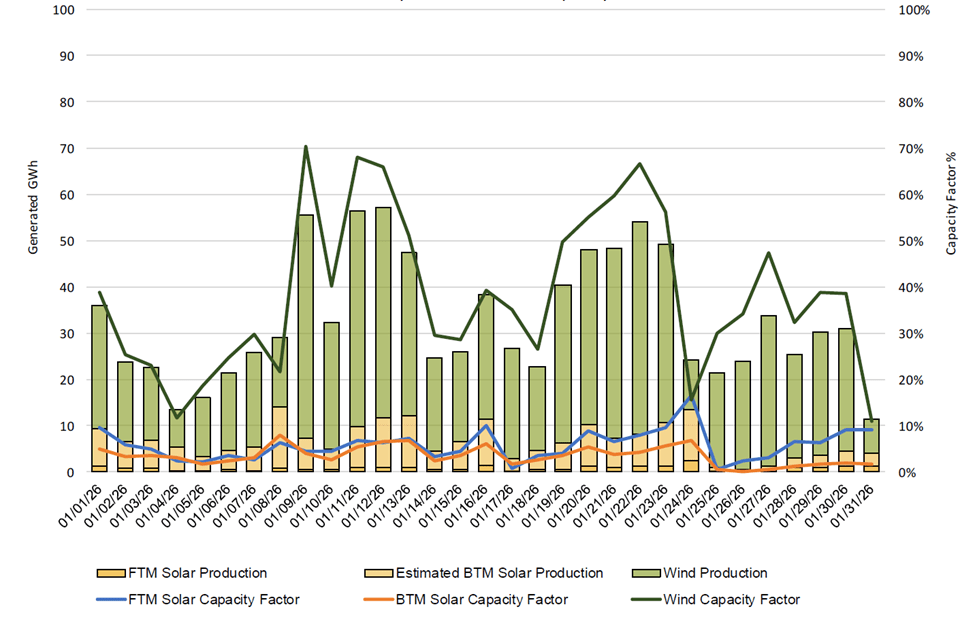

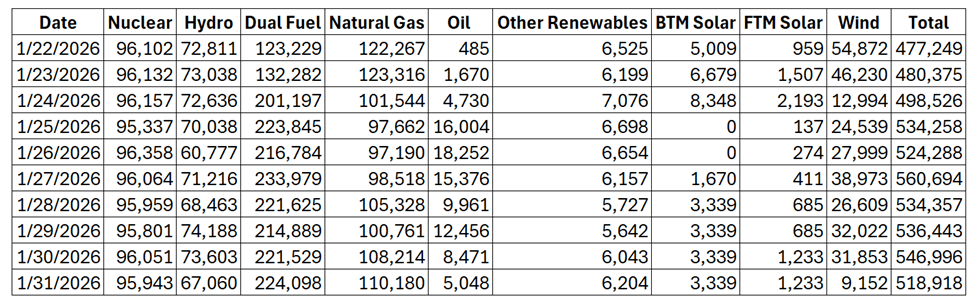

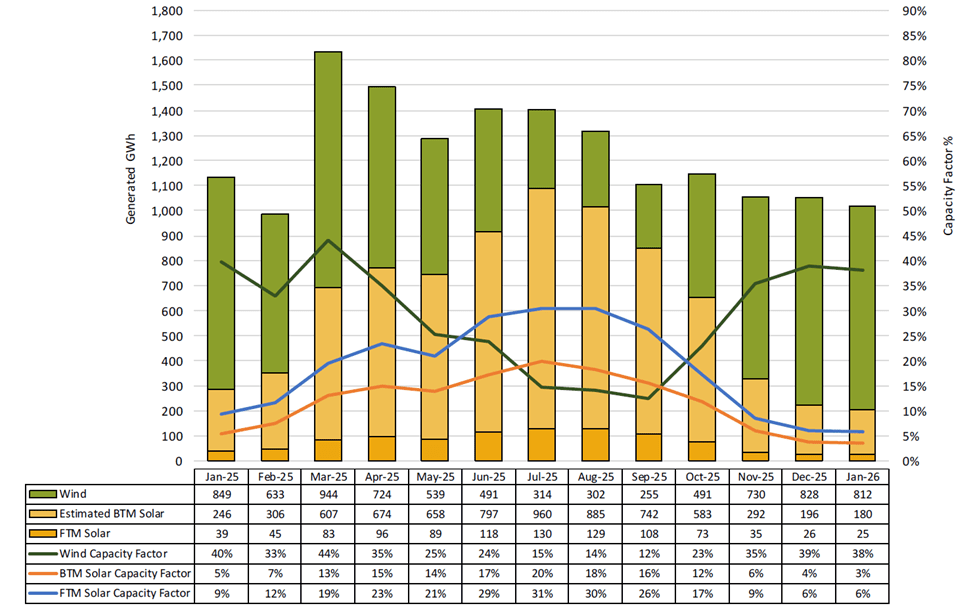

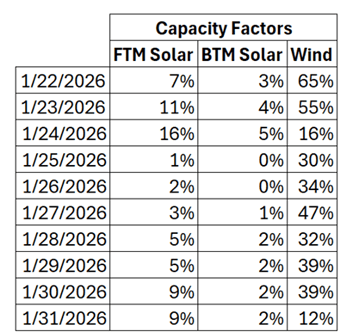

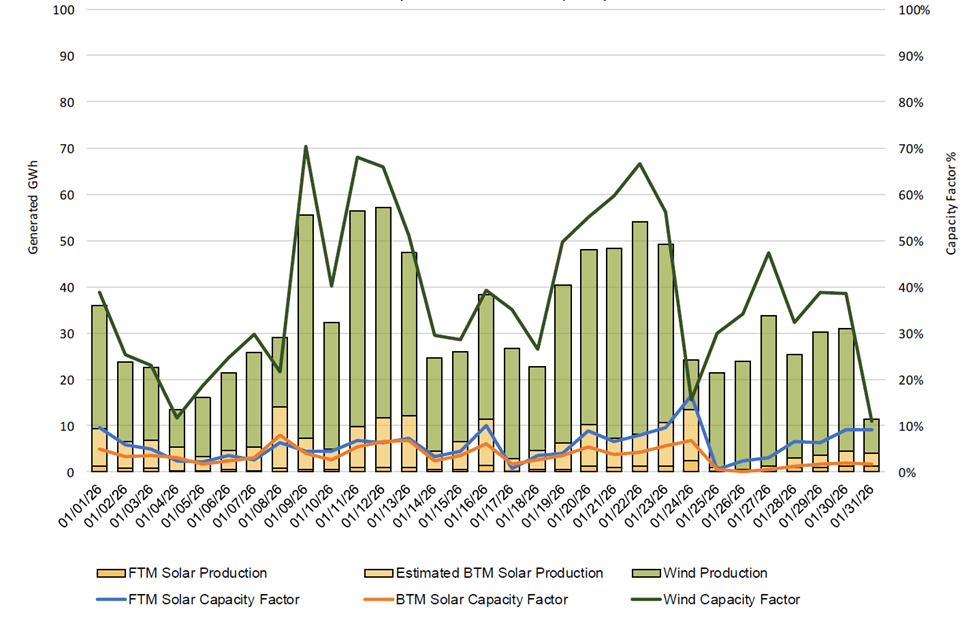

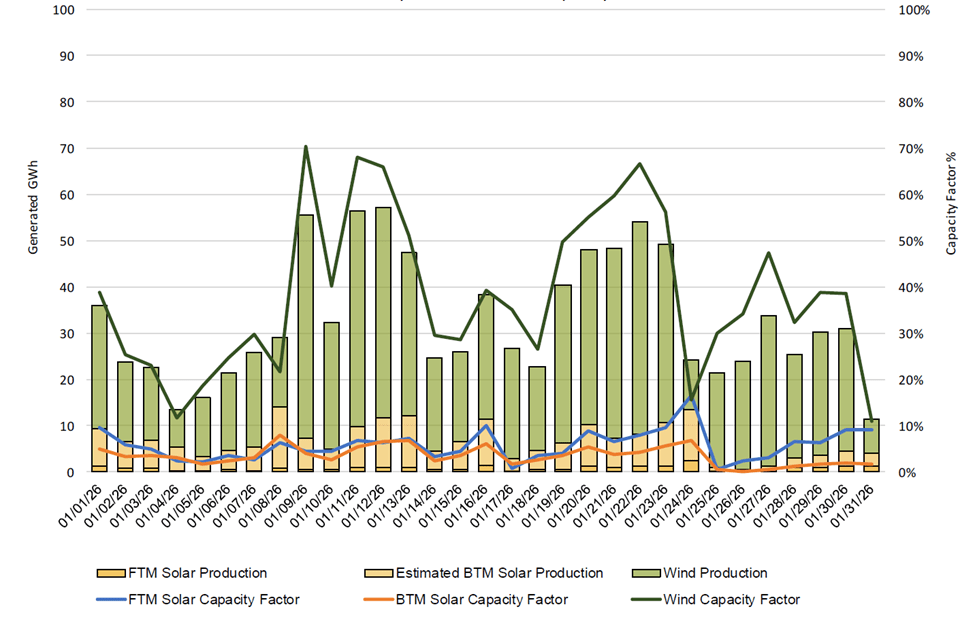

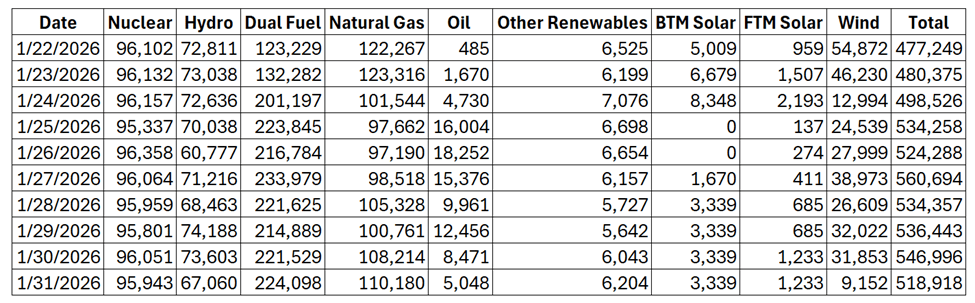

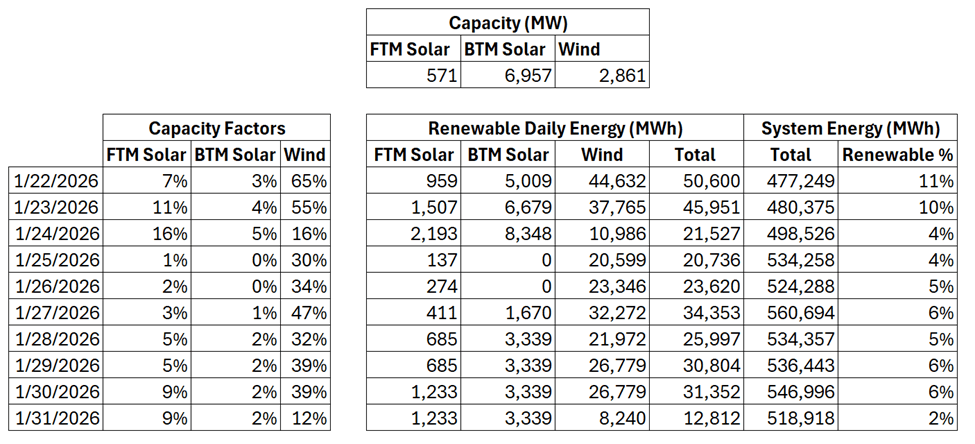

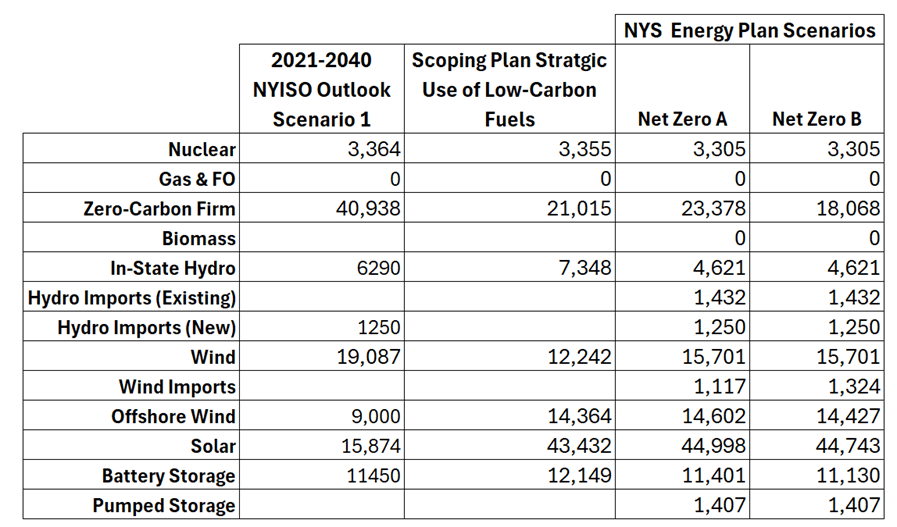

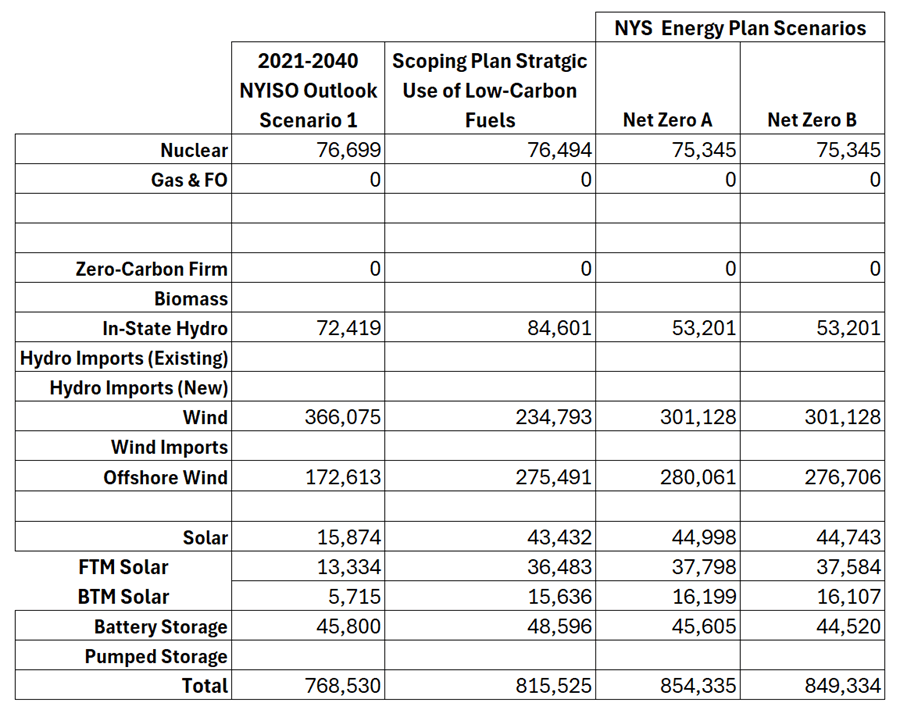

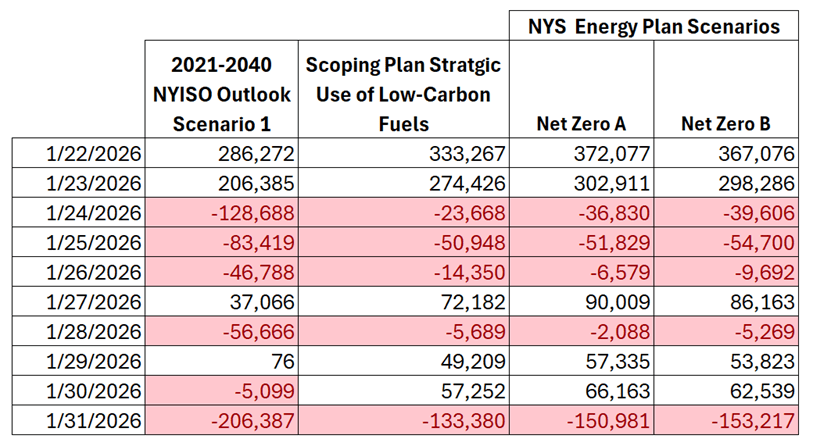

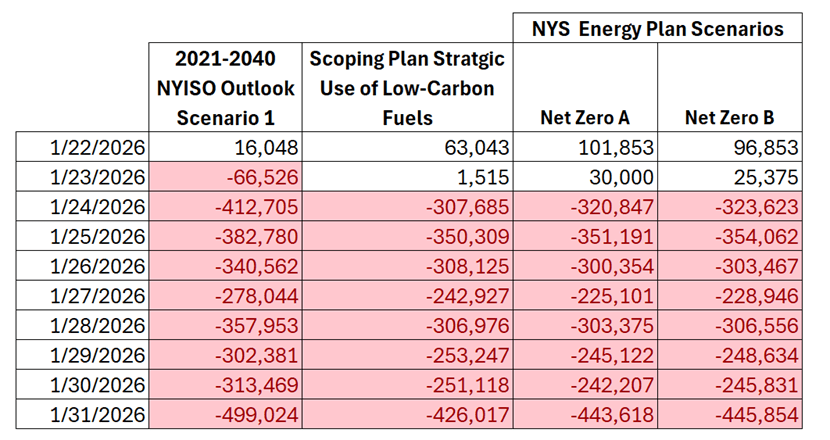

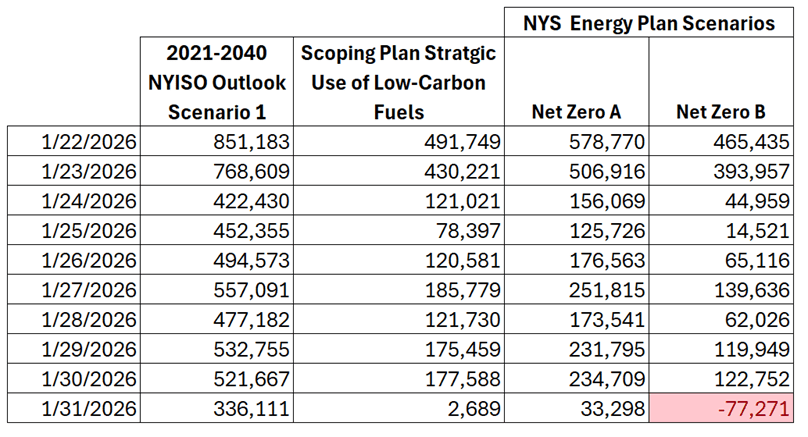

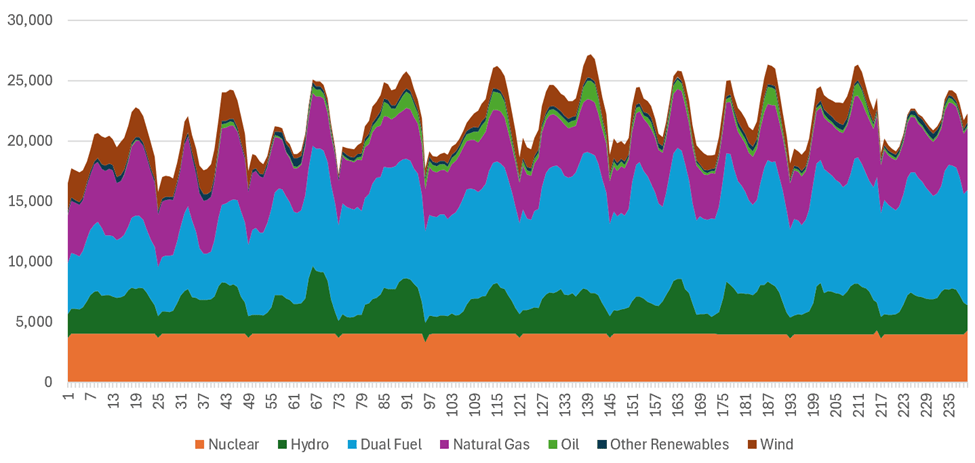

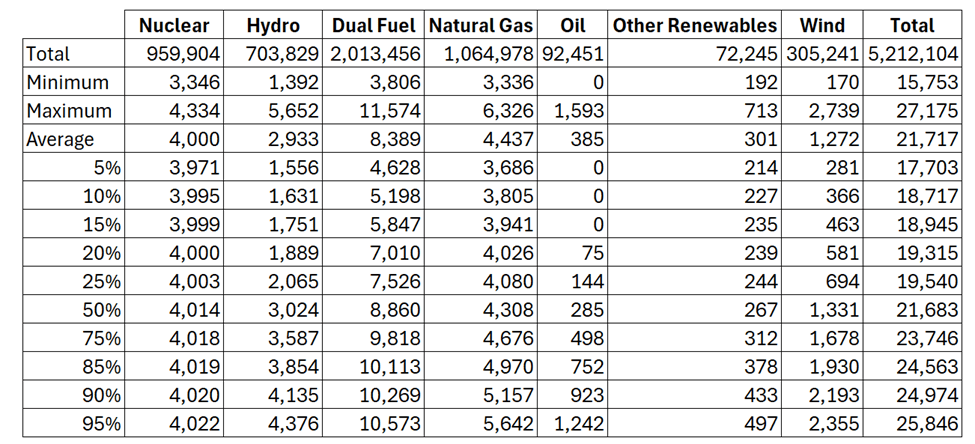

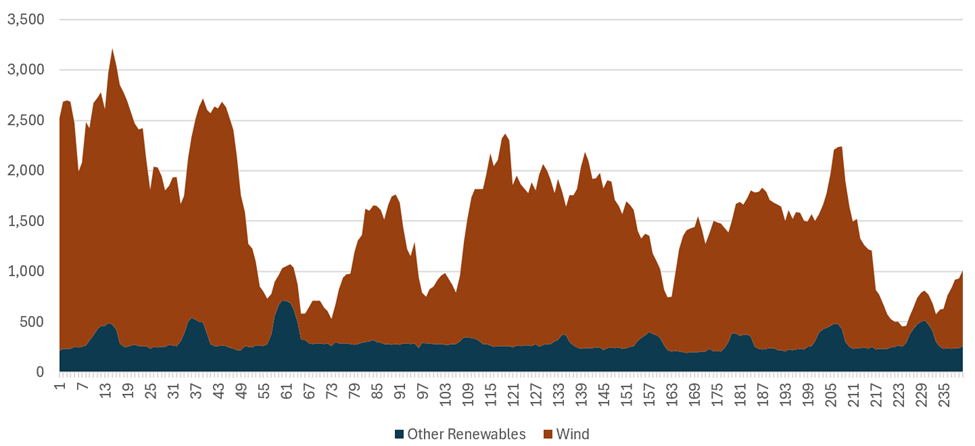

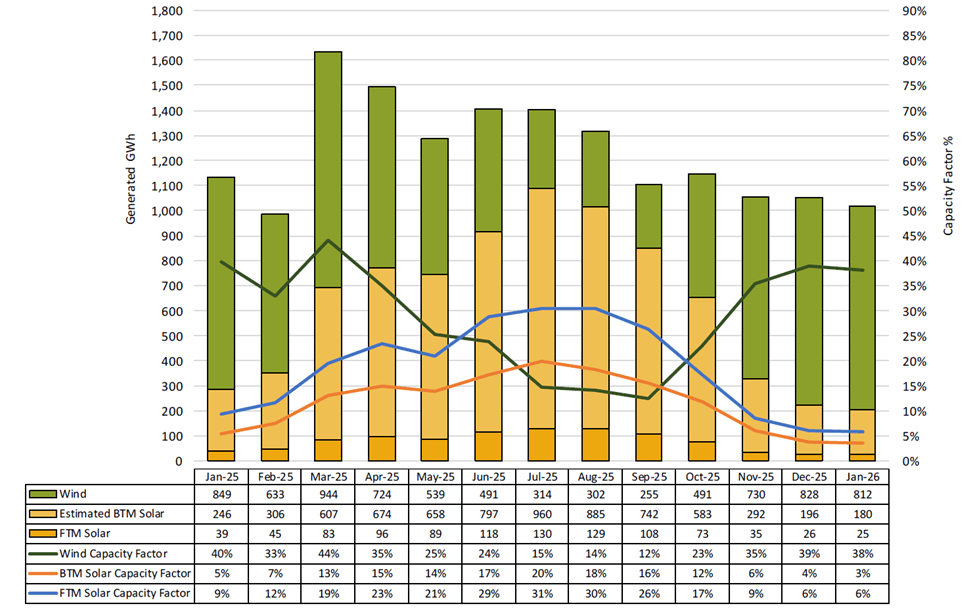

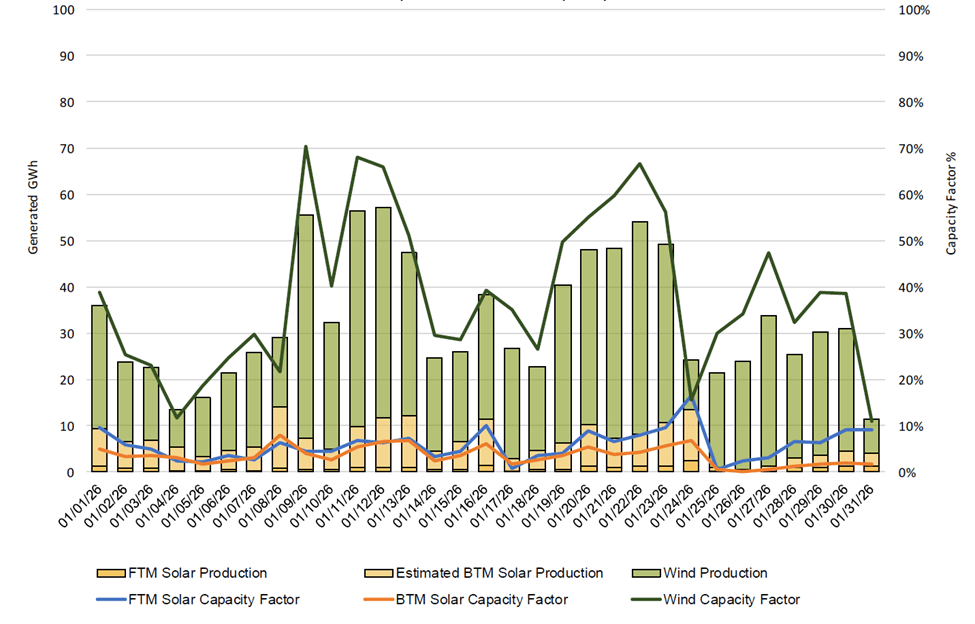

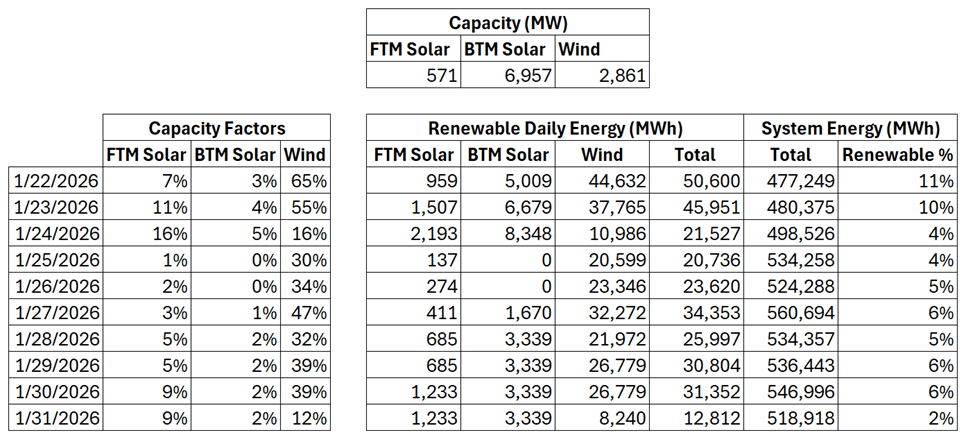

The Climate Act proposes a weather-dependent electric system. We already know what happens when extended periods of low wind and sun line up with high demand. Europe has experienced it and this winter’s weather showed what will happen in New York when there is a dark doldrum period where both wind and solar underperform for days. NYISO data clearly shows that the January 24-27 snowstorm caused both the utility-scale and rooftop solar resources to go to essentially zero on January 25th at the height of the storm. The subsequent period of cold weather prevented melting of the snow covered panels through the end of the month. On January 31, the winds tailed off and the total renewable energy resources only provided 2% of the total energy. The current plans still have no proven, affordable solution for these worst‑case conditions, even as dispatchable fossil units are pushed toward early retirement. That is not bold; it is reckless.

Discussion

Calling anyone who raises these concerns a “denier” is a way of avoiding the hard work of fixing the plan. It flips reality on its head. The truly irresponsible position is to insist that the laws of politics can overrule the laws of physics and economics, and to dismiss the engineers, grid operators, and analysts who point out the contradictions.

New Yorkers deserve better than this false choice between blind faith in an untested transition and caricatures of anyone who dissents. A responsible path forward would:

- Admit that the current schedule and mandates are not aligned with demonstrated technology and cost.

- Use existing safety‑valve and review provisions to pause, reevaluate, and correct course where needed.

- Prioritize reliability and affordability as co‑equal goals with emissions reduction, not afterthoughts.

- Be honest about New York’s tiny share of global emissions and focus on scalable innovations that others might actually adopt.

You can call that pragmatism, skepticism, or just basic due diligence. What it is not, under any honest definition, is “climate denial.” If New York’s climate agenda is as strong as its supporters claim, it should be able to survive tough questions from people who pay the bills and rely on the grid. If it cannot, the problem is not the questions.