One of my pragmatic interests is market-based pollution control programs. As part of New York’s budget process Governor Kathy Hochul announced a plan to use a market-based program to raise funds for Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) implementation that is included in the Budget Bill. I have looked at the language for proposed amendments to the original Budget Bill proposal and am stunned at the disconnect between reality and the perceptions of the authors of the amendments.

I submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan and have written over 290 articles about New York’s net-zero transition because I believe the ambitions for a zero-emissions economy embodied in the Climate Act outstrip available renewable technology such that the net-zero transition will do more harm than good. I also follow and write about the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) market-based CO2 pollution control program for electric generating units in the NE United States. I have extensive experience with air pollution control theory, implementation, and evaluation having worked on every cap-and-trade program affecting electric generating facilities in New York including the Acid Rain Program, RGGI, and several Nitrogen Oxide programs. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Climate Act Background

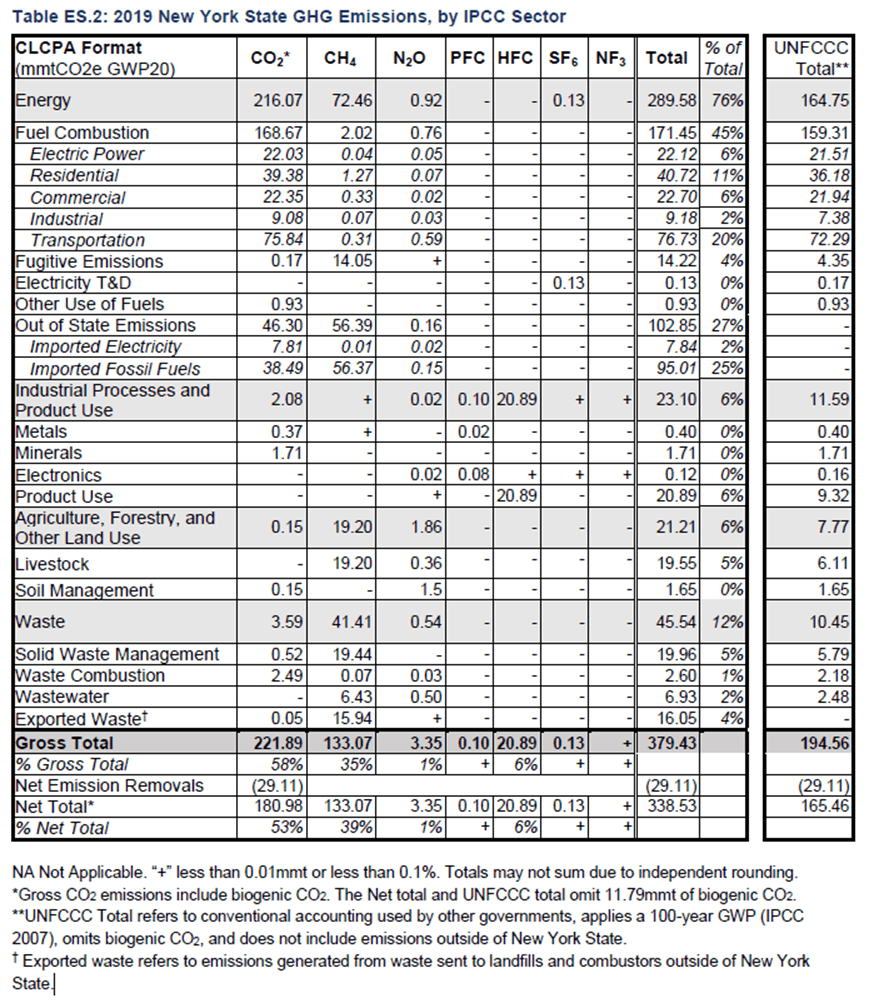

The Climate Act established a New York “Net Zero” target (85% reduction and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. The Climate Action Council is responsible for preparing the Scoping Plan that outlines how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” In brief, that plan is to electrify everything possible and power the electric grid with zero-emissions generating resources by 2040. The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to write a Draft Scoping Plan that was released for public comment at the end of 2021 and approved on December 19, 2022.

The Final Scoping Plan included recommendations for a comprehensive economy-wide policy to support implementation. The recommendations included a cap and invest market-based emissions control approach similar to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). The policy is supposed to provide compliance certainty and “support clean technology market development and send a consistent market signal across all economic sectors that yields the necessary emission reductions as individuals and businesses make decisions that reduce their emissions.” The “market signal” translates into an additional source of funding to implement policies identified in the Scoping Plan. But that’s not all. A key narrative in New York’s version of the Green New Deal is equity and the cap and invest recommendation includes “prioritizing air quality improvement in Disadvantaged Communities and accounting for costs realized by low- and moderate income (LMI) New Yorkers.”

New York Cap and Invest

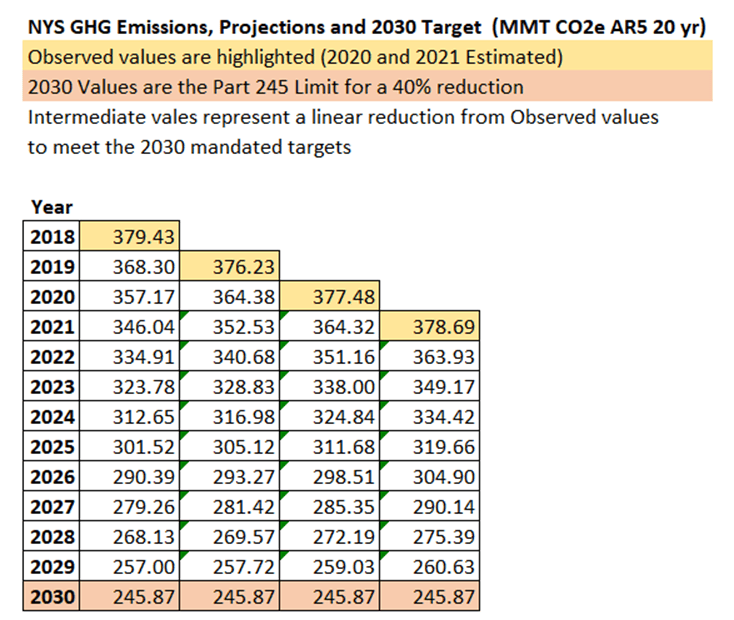

Hochul’s state of the state address included a proposal for a cap and invest program. It stated that “New York’s Cap-and-Invest Program will draw from the experience of similar, successful programs across the country and worldwide that have yielded sizable emissions reductions while catalyzing the clean energy economy.” Subsequently other legislators have jumped on the bandwagon and offered legislation to modify the Hochul proposal. My first article on this plan, initial impression of the New York cap and invest program, gave background information on the Climate Act’s economy-wide strategy and my overarching concerns. I looked at potential revenue targets in a couple of subsequent posts here and here. More recently I compared the emissions reduction trajectory necessary to meet the 40% GHG emission reduction by 2030 mandate relative to observed emissions trends.

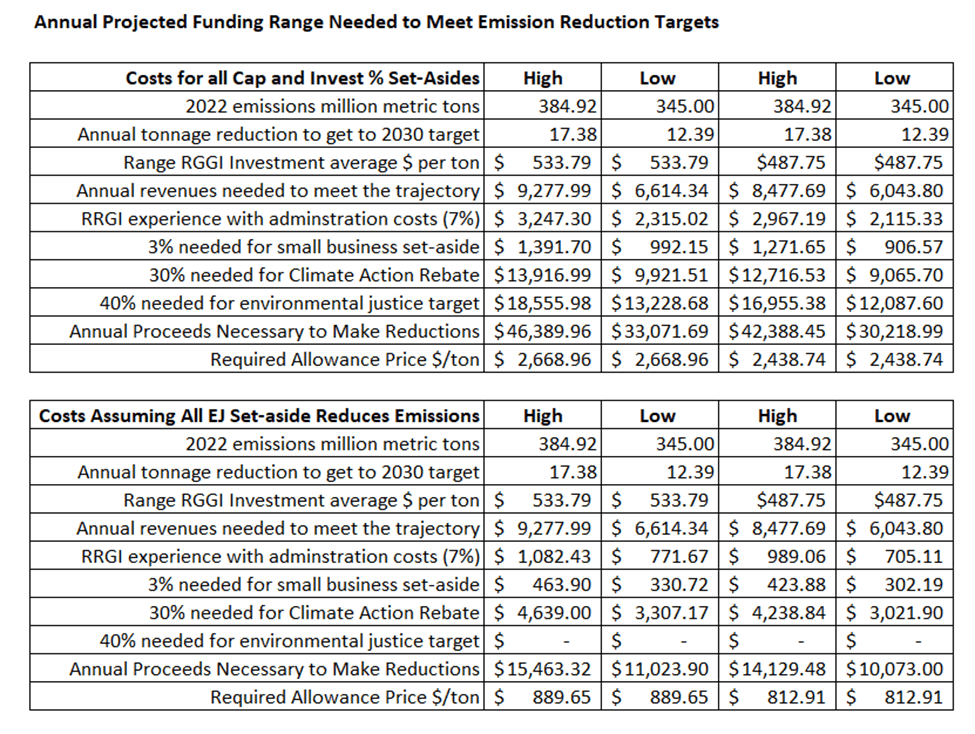

My analyses to date indicate that New York’s belief that the proposed cap and invest program can build on “the experience of similar, successful programs across the country and worldwide” is misplaced. The idea that the RGGI market signal was a significant driver for the observed emissions reductions is inaccurate because the primary driver was fuel switching to cheaper natural gas caused by the fracking success in other states. New York has been investing RGGI auction proceeds for years and the cost per ton reduced is no less than $469. At that rate, if the program were to fund all of the reductions necessary, auction revenues of anywhere between $10 billion per year and over $40 billion per year would be needed depending on the assumptions used. Finally, the required emission reductions per year to meet the 2030 mandate are so aggressive that it is unlikely that there will be sufficient allowances available for all sectors to meet that mandate. The result will be an artificial energy shortage that will limit electric production as well as gasoline and natural gas availability.

Incredibly, the legislative amendments (Senate Bill 4008-B) to the Hochul Administration bill proposal described below would make things worse for New Yorkers.

Fatal Flaws for Cap and Invest

In my opinion, the Hochul Administration and other Progressive legislators have been trying too hard to incorporate environmental and climate justice concerns into the net-zero transition plans. In the first place, I don’t think that constituency will ever be satisfied because their insistence on zero-risk policies ultimately requires a shut down of all power sources. There is no benign way to make power or use energy so ignoring the possibility of pragmatic tradeoffs means they will never be placated. Worse, their rationale for the tenets of their beliefs is flawed.

The Climate Act requires the state to invest or direct resources in a manner designed to ensure that disadvantaged communities to receive at least 35 percent, with the goal of 40 percent, of overall benefits of spending on:

- Clean energy and energy efficiency programs

- Projects or investments in the areas of housing, workforce development, pollution reduction, low-income energy assistance, energy, transportation, and economic development

In order to implement these goals, the Climate Act created the Climate Justice Working Group (CJWG) which is comprised of representatives from Environmental Justice communities statewide, including three members from New York City communities, three members from rural communities, and three members from urban communities in upstate New York, as well as representatives from the State Departments of Environmental Conservation, Health, Labor, and NYSERDA. The 22 members of the Climate Action Council were chosen mostly because of their ideology but most at least had relevant expertise. None of the representatives appointed to the CJWG outside of the agency staff have any energy or climate science background. Nonetheless, all of their comments on the Draft Scoping Plan were explicitly addressed and responses to their concerns are evident in the cap and invest plan.

There are four CJWG concerns that legislators are trying to incorporate into the cap and invest proposed laws or are in the Climate Act itself that make the proposed approach unworkable. Their four concerns are “hot spots”, allowance banking, allowance trading, and the use of offsets. I will address each one below. In each case, CJWG members, climate activists, and environmental justice advocates have seized on an issue based on poor understanding or something else and are demanding their concerns be considered and the legislators are addressing their concerns.

Hot Spots

As mentioned previously a key consideration in the Climate Act is “prioritizing air quality improvement in Disadvantaged Communities”. Chapter 6. Advancing Climate Justice in the Scoping Plan states:

Prioritizing emissions reduction in Disadvantaged Communities should help to prevent the formation or co-pollutant emissions despite a reduction in emissions statewide. A broad range of factors may contribute to high concentrations of pollutants in a given location that create a hotspot. The result can be unhealthy air quality, particularly for sensitive populations such as expectant mothers, children, the elderly, people of low socio-economic status, and people with pre-existing medical conditions.

The poster child for egregious harm from hotspots is fossil-fired peaking power plants. I believe the genesis of this contention is the arguments in Dirty Energy, Big Money and I have shown that that analysis is flawed because it relies on selective choice of metrics, poor understanding of air quality health impacts, unsubstantiated health impact analysis, and ignorance of air quality trends. In this context, I have seen indications that there are people who believe that GHG emissions themselves have some kind of air quality impact exacerbated in disadvantaged community hot spots. That is simply wrong – there are no health impacts associated with carbon dioxide emissions at current observed ambient levels. Dirty Energy, Big Money and arguments in the Scoping Plan are based on co-pollutant emissions (NOx and PM2.5) that allegedly cause impactful hot spots that result in unhealthy air quality. Note that all facilities in New York State have done analyses that prove that their emissions do not directly produce concentrations in the vicinity of power plants that contravene National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) mandated to protect human health and welfare. Trying to make the cap and invest program, that is appropriate for controlling GHG emissions to mitigate global warming, also address a neighborhood air quality problem already covered by other air quality rules is not in the best interests of a successful cap and invest program. I do not know how the allowance tracking system could be modified to address hot spots without creating major unintended consequences.

Allowance Banking

The proposed amendments to Hochul’s budget bill include a new section to the existing Climate Act law. Proposed § 75-0123. Use of allowances states that:

- Allowances must be submitted to the department for the full amount of greenhouse gas emissions emitted during such compliance period. If greenhouse gas emissions exceed allowances submitted for the compliance period, such shortfall shall be penalized pursuant to section 75-0129 of this article.

- Any allowances not submitted at the end of the compliance period in which they are issued by the authority shall automatically expire one hundred eighty days after the end such compliance period if not submitted prior to such date.

The provision for expiring allowances would prohibit allowance banking. Allowance banking is a feature of all existing cap and trade programs and is one of the reasons that they have been successful. Banking enables affected sources to handle unexpected changes in operation, compliance monitoring problems, and long-term planning.

The authors of this amendment have not figured out that the primary source of GHG emissions is energy production. One major difference between controlling CO2 and other pollutants is that there are no cost-effective control technologies that can be added to existing sources to reduce emissions. Combine that with the fact that CO2 emissions are directly related to energy production, the result is that after fuel switching the primary way to reduce emissions is to reduce operations. Consequently, CO2 emission reductions require replacement energy production that can displace existing production.

A feature of RGGI that addresses the link between energy use and CO2 emissions is a three-year compliance period with banking. It is included because it was recognized that in a year when it is either really cold or really hot GHG emissions go up as energy use goes up. In a year when it is mild, energy use goes down and emissions go down. To address that variability RGGI has a three-year compliance period and allows sources to bank allowances for this balancing inter-annual variability. The inevitable result of this amendment language would be insufficient allowances in a year with high energy use and that translates to an artificial shortage of energy.

Allowance Trading

There is no better example of ideological passion over-riding reality than language in the proposed amendments to Hochul’s budget bill that prohibits allowance trading. Proposed § 75-0123. Use of allowances states that:

3. Allowances shall not be tradable, saleable, exchangeable or otherwise transferable.

Words cannot describe how little I think of the authors’ understanding of cap and invest based on this language. Cap and invest programs are a form of cap-and-trade programs. Anyone who thinks that a program that excludes allowance exchanges has no concept whatsoever of how these programs are supposed to work and how they have been successfully working.

Offsets

There is one aspect of the proposed cap and invest legislation that is conspicuous by its absence – offsets. In RGGI a CO2 offset allowance represents “a project-based greenhouse gas emission reduction outside of the capped electric power generation sector.” In the California program Offset Credits are issued to “qualifying projects that reduce or sequester greenhouse gases (GHG) pursuant to six Board-approved Compliance Offset Protocols.” Recall that Hochul stated that “New York’s Cap-and-Invest Program will draw from the experience of similar, successful programs across the country and worldwide that have yielded sizable emissions reductions while catalyzing the clean energy economy.” Furthermore, the Climate Act has a net-zero target. In other words, emissions from certain sectors that can never be expected to reduce their GHG emissions to zero (like aviation) will have those emissions offset by programs that reduce or sequester GHG emissions.

In a rational world, it is obvious that the agriculture and forestry sectors that are the likely sources of most offsets in New York would get incentives to develop offsets compliant with qualification protocols used in other successful programs. After all the Climate Act needs offsets to meet its net-zero targets and offset programs are components of the similar, successful programs New York wants to emulate.

New York’s Climate Act is not rational. Chapter 17 in the Final Scoping Plan explains why offsets are not mentioned:

The inclusion of offset programs in some cap-and-invest programs, such as RGGI, has engendered some criticism, particularly from environmental justice organizations that contend that the availability of offsets reduces the certainty of emission reductions from the regulated sources. In any cap-and-invest program adopted to meet Climate Act requirements, the role of offsets would have to be strictly limited or even prohibited in accordance with the requirements of ECL § 75-0109(4). Under that provision, DEC would have to ensure that any Alternative Compliance Mechanism that is adopted would meet various requirements specified in that provision of the Climate Act. Therefore, offsets would have little, if any, role under a cap-and-invest program designed to comply with the Climate Act.

In short, because there was “some criticism” from environmental justice organizations, the Progressive Democrats in control of the Administration and Legislature are excluding this “important cost-containment element” used in other successful programs. Given that offsets are a necessary component for meeting the net-zero by 2050 target I expect that a different subsidy will be used to incentivize offsets.

Conclusion

There are four CJWG concerns that legislators are trying to incorporate into the cap and invest proposed laws or are in the Climate Act itself that will make New York’s cap and invest plan fail. All cap and invest programs are intended to reduce emissions that have regional or global impacts. Trying to combine cap and invest global obligations with “hotspot” neighborhood air quality obligations already covered by other air quality rules would be difficult if not impossible to do without unintended consequences. Prohibiting allowance banking eliminates a compliance mechanism widely used in all existing emission market programs. Cap and invest is a variant of cap-and-trade emission market programs so eliminating trading is absurd. Emission offsets are a necessary component of economy-wide net-zero targets. If offsets are prohibited in the cap and invest plan they will be subsidized elsewhere.

A primary component of New York’s Climate Act and cap and invest legislation was to address climate justice. I do not dispute that is a reasonable goal but appeasement of the naïve and misguided demands of the CJWG on cap and invest components will make that program unworkable and cause reliability, affordability, and safety problems. When those problems occur, the communities that will be impacted the most will be the ones this mis-guided appeasement is intended to protect.