James Hanley from the Empire Center published Ten Reasons the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act May Cost More than It’s Worth (“Ten Reasons”) that explains why massive political promises like the Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act (Climate Act) often cost more than they’re worth, wasting taxpayers’ money. While I agree with his ten reasons, this post explains why the costs are even worse than he describes.

I submitted comments on the Climate Act implementation plan and have written over 275 articles about New York’s net-zero transition because I believe the ambitions for a zero-emissions economy embodied in the Climate Act outstrip available renewable technology such that the net-zero transition will do more harm than good. The opinions expressed in this post do not reflect the position of any of my previous employers or any other company I have been associated with, these comments are mine alone.

Background

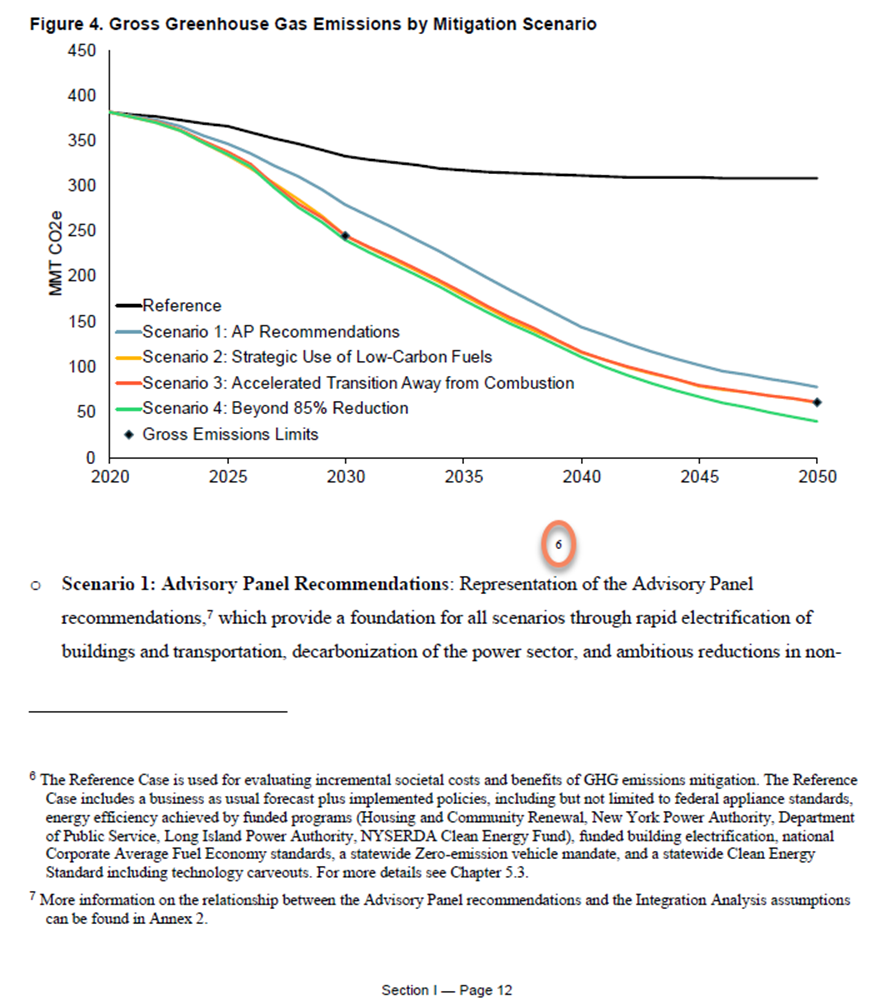

The Climate Act established a “Net Zero” target (85% reduction and 15% offset of emissions) by 2050. The Climate Action Council is responsible for the Scoping Plan that outlines how to “achieve the State’s bold clean energy and climate agenda.” In brief, that plan is to electrify everything possible and power the electric gride with zero-emissions generating resources by 2040. The Integration Analysis prepared by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and its consultants quantifies the impact of the electrification strategies. That material was used to write a Draft Scoping Plan that was revised in 2022 and the Final Scoping Plan was approved on December 19, 2022. In 2023 the plan is to develop regulations and legislation to implement the Scoping Plan recommendations.

In the following section I reproduce Hanley’s post with my bold italicized comments.

Ten Reasons

Over budget, over time, over and over – that’s the iron law of megaprojects.

Megaprojects are transformational, multi-billion-dollar, multi-year projects involving numerous public and private stakeholders. 90 percent come in over budget, often two, three or even more times over, and they often underdeliver on the promised benefits.

In short, despite political promises to the contrary, they often cost more than they’re worth, wasting taxpayers’ money.

Some notable examples of megaproject cost overruns include California’s high speed rail (years behind schedule and at least three times over budget), Boston’s Big Dig (completed five years late and more than five times over budget) and New York’s own Long Island Railroad East Side Access (12 years behind schedule and – with a budget that’s grown from $3.5 billion to between $11 and $15 billion – three to four times over budget). And that’s not New York’s only over-budget transit project.

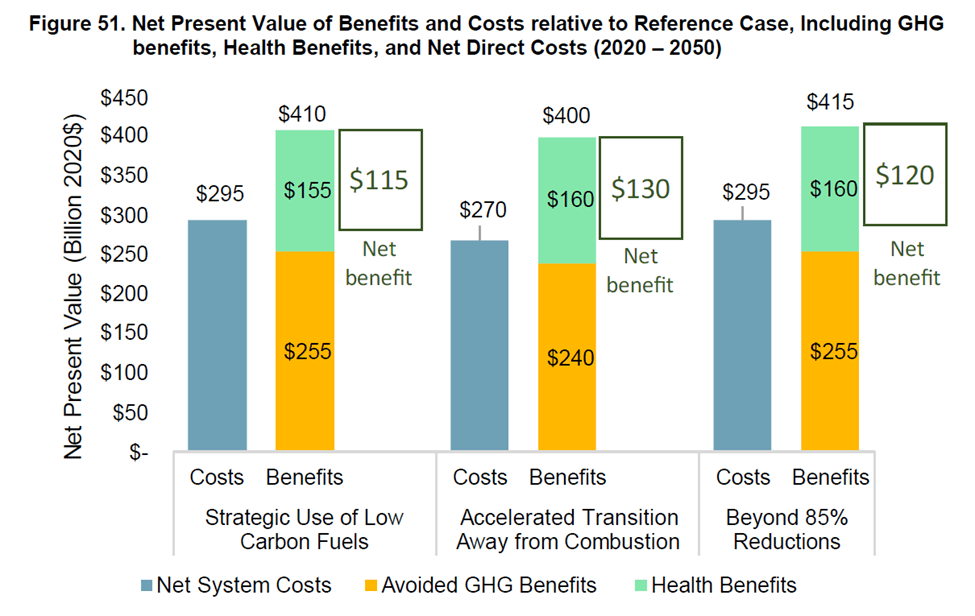

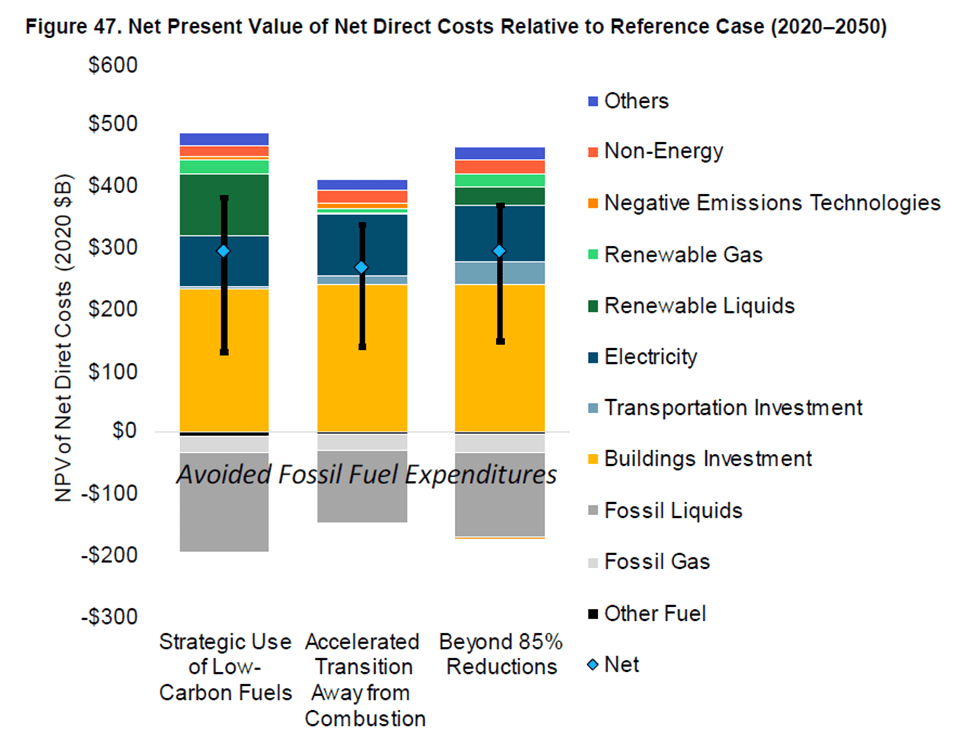

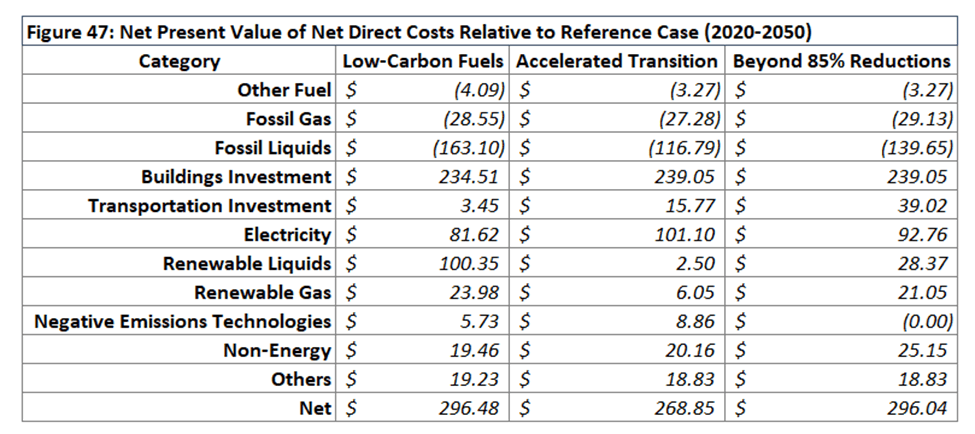

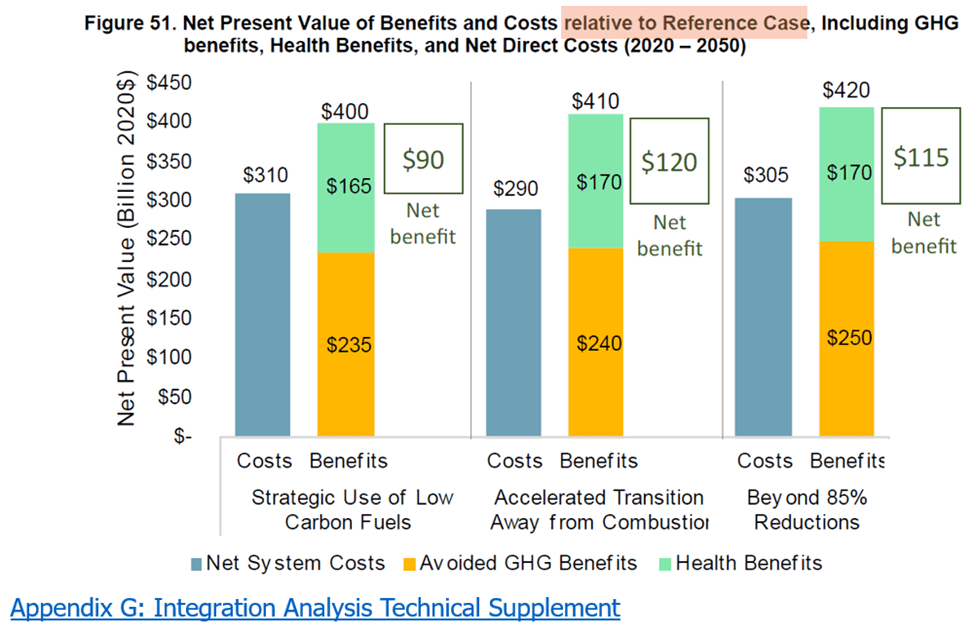

Those are all small potatoes compared to New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). The overall benefit-cost analysis for the CLCPA predicts a cost of $280-$340 billion – around 20 times the cost of the East Side Access project – to radically transform New York to a net-zero greenhouse gas emissions economy. The benefit is supposed to be $420-$430 billion, for a net gain of $80-$150 billion.

The Scoping Plan benefit-cost analysis is a shell game disguising misleading and inaccurate information. In short, the $280-$340 billion costs only represent the costs of the Climate Act itself and not the total costs to meet the net-zero by 2050 target. The Scoping Plan costs specifically exclude the costs of “Already Implemented” programs including the following:

- Growth in housing units, population, commercial square footage, and GDP

- Federal appliance standards

- Economic fuel switching

- New York State bioheat mandate

- Estimate of New Efficiency, New York Energy Efficiency achieved by funded programs: HCR+NYPA, DPS (IOUs), LIPA, NYSERDA CEF (assumes market transformation maintains level of efficiency and electrification post-2025)

- Funded building electrification (4% HP stock share by 2030)

- Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards

- Zero-emission vehicle mandate (8% LDV ZEV stock share by 2030)

- Clean Energy Standard (70×30), including technology carveouts: (6 GW of behind-the-meter solar by 2025, 3 GW of battery storage by 2030, 9 GW of offshore wind by 2035, 1.25 GW of Tier 4 renewables by 2030)

The Scoping Plan documentation is not sufficiently detailed to determine the expected costs of these programs or to determine if the benefits calculations included the benefits of the emission reductions from these programs. I have not doubt, however, that if these costs are included that the total would be greater than the benefits and I suspect very strongly that the benefits from these programs were included even if the costs were not. The shell game definition: “A fraud or deception perpetrated by shifting conspicuous things to hide something else” is certainly an apt description of the Scoping Plan benefit-cost analysis.

That’s a good deal, if it really works out that way. Unfortunately, based on the history of megaprojects, it’s unlikely to provide so much benefit.

Based on my evaluation it is not a good deal from the get go. All of Hanley’s discussion of megaprojects below is in addition to the inaccurate starting point.

If we take the lower end cost estimate and assume the policy only costs half again as much – which would make it a rare megaproject success story – the cost would rise to $420 billion, exactly wiping out the lower end estimate of the gains.

If it came in at twice the low-end cost estimate – which is common for such big and complex programs – it would cost $560 billion, resulting in a net loss of at least $220 billion. Three times over budget would mean a net loss of at least $410 billion – closing in on half a trillion dollars wasted.

And if the benefits are less than predicted – which is also common – the outcome gets even worse.

The issue is not that there aren’t any benefits. At least some of the claimed benefits are real. But just like buying a car or a meal, it’s possible to overpay for what we’re getting.

Part of the general reason for the predictable cost overruns is that these projects tend to be exceptionally complex and innovative, novel ideas which nobody really knows how to execute well due to lack of experience. New York’s CLCPA-supporting politicians and advocates love to boast about the CLCPA being a nation-leading policy, which is to say it’s something nobody has experience doing.

Another reason – known both from research and from the mouth of a famous politician – is that advocates sometimes intentionally mislead the public about the costs and benefits of megaprojects. Perhaps no CLCPA supporters are consciously lying about its costs, but it seems evident that it would be uncomfortable for them to dig deeply into the issue of megaproject cost, and whatever doubts they may have they are not voicing them.

Ultimately the Climate Act is a political initiative designed to appeal to specific constituencies within the state. In that context the Scoping Plan itself is just a tool to cater to those constituencies. Authors of the Scoping Plan may not have lied but they did intentionally mislead the public as I have explained in posts and comments. The response to comments submitted did not address any of the issues I raised.

But we shouldn’t look at the CLCPA as just a single megaproject. It’s actually a large group of them. Among the projects within the CLCPA that are, or may ultimately scale up to the size of, megaprojects are:

- The build-out of electric vehicle charging infrastructure;

- Transitioning the state’s school buses to all electric;

- Transitioning the state’s public transit buses to all-electric;

- Promotion of smart-growth for mobility-oriented (biking and walking) development.

- Electrifying 85 percent of residential/commercial space by 2050;

- Achieving 70 percent renewable electricity by 2030;

- Developing 6 megawatts of battery storage;

- Building 9,000–18,000 megawatts of offshore wind;

- Building the grid for renewable energy transmission;

- The overall agricultural and forestry portion of the CLCPA Scoping Plan;

- Achieving dramatic reductions in the amount of solid waste being produced and disposed of;

- Decarbonizing the statewide natural gas distribution system.

That comes to at least 12 distinct policy areas within the CLCPA that are each likely to be multi-billion dollar projects on their own. Depending on how one analyzes the Act and its Scoping Plan, this may be an incomplete list.

Keep in mind the “already implemented program” costs in the $280-$340 billion costs of the Scoping Plan. Those programs at least include: The build-out of electric vehicle charging infrastructure; transitioning the state’s school buses to all electric; transitioning the state’s public transit buses to all-electric; developing 3 MW of the 6MW of battery storage; and building 9,000 MW of the 18,000 MW of offshore wind.

This means at least 12 opportunities for mega-failure in the CLCPA. And with 90 percent of megaprojects coming in over budget, we should expect at least 10 or 11 of these to experience substantial cost overruns.

But saying that megaprojects tend to come in over budget and short on benefits is not enough. It’s fair to ask why this particular set of megaprojects that collectively make up the CLCPA are likely to do so. So, in addition to the sheer innovative complexity of the CLCPA’s bid to transition New York to a net zero economy, here are 10 reasons why the Climate Act’s costs may be understated, and its benefits overstated.

- Inflation Bites

Projects that take multiple years to complete face the risk of inflation. When the CLCPA’s benefit-cost analysis was conducted, the analysts could not have anticipated that inflation would surge, pushing up the cost of materials and labor. Particularly hard hit so far have been offshore wind projects.

Inflation has moderated somewhat lately, but on-going large federal deficits could cause it to remain at higher levels than anticipated.

- Cap-and-Invest May Cause Business Flight

Policies that cap emissions of particular chemicals, then reduce those caps over time and allow trading of emissions allowances, can be the most cost-effective way of reducing emissions when done at the national or multi-national level. Even if businesses move their operations to another country, a tariff on their emissions can be levied to either make businesses pay for those emissions or incentivize firms to reduce them.

But cap-and-invest is ill-suited to the state level. First, it is easier for businesses to move out of state – or refuse to move into the state – than to move out of country. It is likely that other states competing for business investment will use the Empire State’s emissions cap as a way to leverage firms to look to their states for investment rather than to New York.

This means a state-level cap-and-invest scheme is likely to diminish business investment, reducing the state’s economic growth and therefore tax revenues.

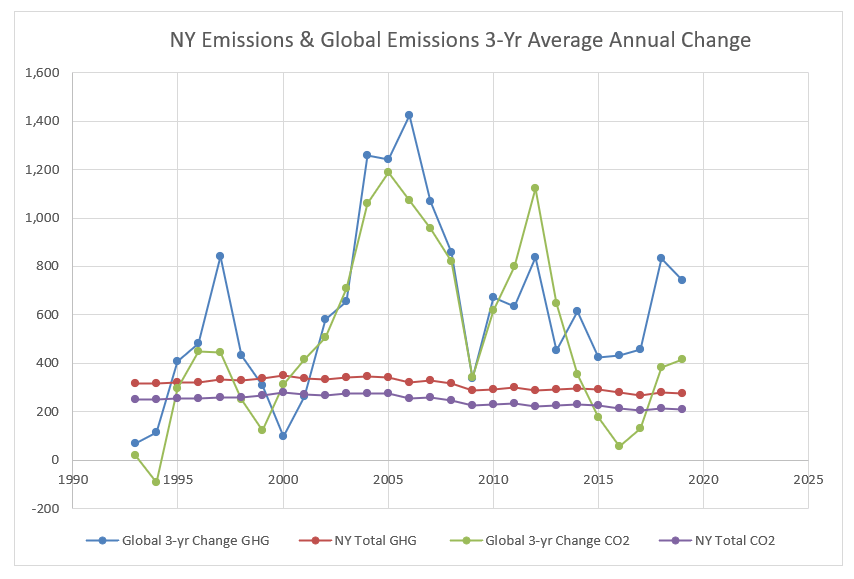

Second, a state cannot enact an emissions tariff because it would violate the U.S. Constitution’s interstate commerce clause, so there is no cudgel to force emissions reductions on businesses that move operations out of state. This means less overall reduction in greenhouse gas emissions because those emissions just occur elsewhere.

This emissions “leakage,” and loss of tax revenue, can also occur if GHG-emitting in-state businesses become less competitive due to compliance costs and lose market share to out-of-state competitors.

This kind of leakage has long plagued California’s cap-and-trade program. In New York’s case, because a majority of the CLCPA’s claimed benefits come from greenhouse gas reductions, it means a potentially very large reduction in the benefits of the policy.

To minimize business flight and emissions leakage, the Climate Action Council proposes giving away emissions allowances to emissions-intensive and trade-exposed businesses – those that are most likely to find it more cost-effective to leave than to buy emissions allowances. But this may only be a temporary reprieve for these industries, as the number of emissions allowances is required to decline over time, and some businesses may never find it more cost-effective to reduce their emissions than to move operations out of state.

Giving away emissions allowances also means the state will take in less revenue from auctions of emissions permits, having given away many for free, and so will have less money to invest in CLCPA policies, further reducing the law’s benefits.

- Union Job Requirements Drive Up Costs

The Climate Action Council’s Scoping Plan – the roadmap for Climate Act implementation – calls for the use of union labor and project-labor agreements. But jobs go on the cost side of the ledger rather than the benefits side, so anything that increases the cost of labor increases the overall cost of the policy.

How much this will drive up the total cost of the Climate Act has not been analyzed, but past reporting by the Empire Center shows that prevailing wage requirements can add 13 to 25 percent to project costs. And it’s not as though there aren’t New Yorkers willing to give the public a better deal – around two-thirds of workers in New York’s construction sector are non-unionized, but they will be locked out of CLCPA projects. - Overbuilding of Renewable Energy and Building Energy Backup Is Costly

The most undeniable truth about wind and solar power is that they are unreliable – the wind can fail, the sky can become clouded or night can fall, just when you need the electricity most. According to the New York Independent System Operator, New York must develop 15-45 GW of dispatchable zero-emission electricity generation resources. That’s in comparison to a total of roughly 40 gigawatts of total installed capacity today, and it must be in addition to any new wind and solar power developments.

At a minimum, this means we have to overbuild solar and wind resources in the hopes that somewhere in the state the wind will be blowing and the sun shining. But because New York is too geographically small to ensure that the wind is always blowing, or the sun always shining, somewhere in the state, New York will also need to build backup energy sources.

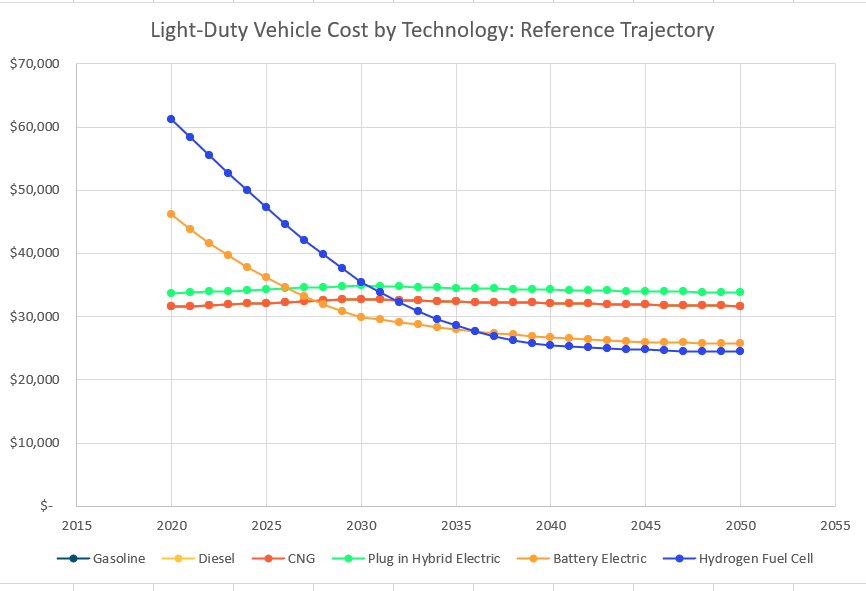

What these greenhouse gas emission-free resources will be – and how much they will cost – is currently unknown, because none are yet commercially available or competitively priced. Hydrogen is a possibility, but the cost will have to fall dramatically and quickly to keep backup power affordable.

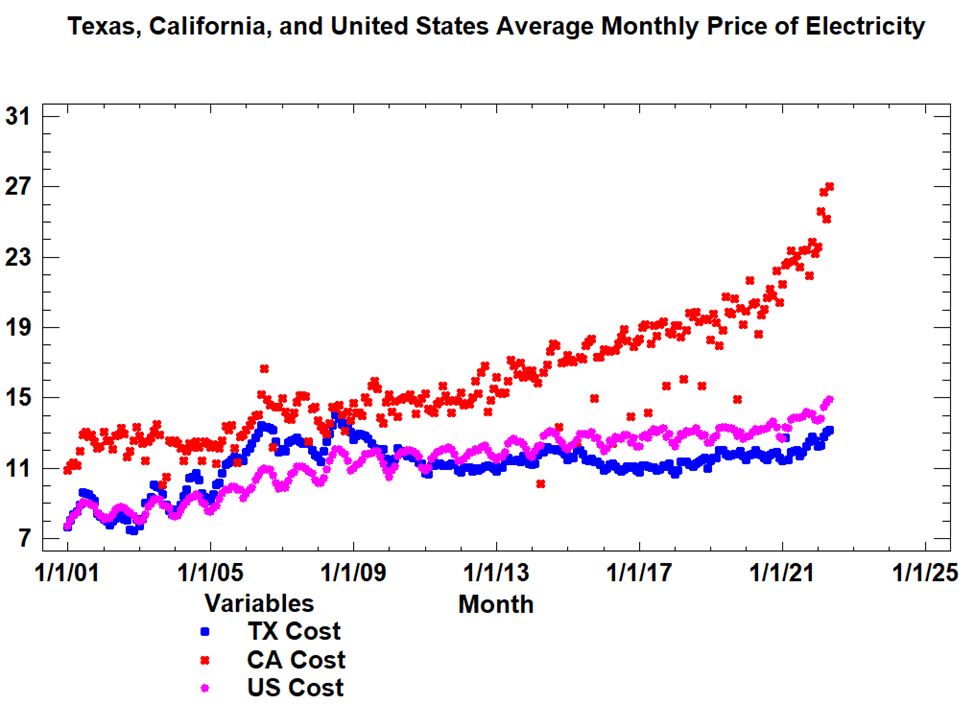

Batteries are also intended to be part of the backup system, although they are only good for meeting peak demand for a few hours. They are currently very expensive, even though – like all technologies – the learning curve continues to push down their price. However, materials costs for batteries may remain high for years, because demand is growing rapidly while supply chains are hindered both by political opposition to minerals mining and geopolitical constraints on mining and refining. - The Cost of Redeveloping the Grid Is Unpredictable

New York currently has, in effect, two largely – although not completely – separate power grids. One is upstate and draws heavily on hydroelectric and nuclear power. The other is mostly downstate and based on natural gas and dual-fuel power plants. Both are based on controllable and dispatchable forms of electricity production.

To eliminate fossil fuel electricity generation and rely much more heavily on variable, uncontrollable, sources like wind and solar, New York must expand its transmission grid to move electricity from where it will be produced – primarily upstate and off-shore – to where it is needed. But this grid will have to be built so that energy can be delivered from whichever sources happen to be producing at a given time, which means more miles of high voltage transmission lines than ever before.

Experts can make a first-pass estimate of the cost of building out all this new transmission, but the complexity of working through multiple political jurisdictions and satisfying numerous stakeholders is one of the leading causes of megaproject cost overruns. Few people want high-voltage transmission lines near their homes, and merely fighting the political battles to site these lines across numerous municipalities and counties could drive up the end cost significantly.

There is another aspect of the transmission system that the Scoping Plan glossed over. Because wind and solar resources are inverter-based they do not provide ancillary services necessary to keep the transmission system stable. As far as I can tell this issue was not addressed by the Scoping Plan and that means there are unaddressed technological and cost issues.

- The Jones Act Increases Offshore Windpower Costs

The Jones Act is a law requiring ships moving cargo between U.S. ports to be U.S. built, owned, crewed, and flagged. There are no Jones Act compliant off-shore wind turbine building vessels in the U.S., although at least one is under construction (at an inflated cost because it has to be U.S. built). Because of the Jones Act, the available ships have to operate out of Canada or rely on the more expensive and dangerous process of having Jones Act compliant “feeder barges” bring materials out to the work site. - The True Social Cost of Carbon Is Unknown

Most of the benefit of the Climate Act doesn’t go to New Yorkers but is a world-wide benefit from the reduction of CO2 emissions. To estimate this benefit, a social cost per ton of CO2 has to be estimated. New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) set the cost at $124 per ton for 2022, rising each year.

But nobody truly knows the social cost of CO2. The number varies wildly between different models used to estimate it. The Biden administration has tentatively set the social cost of CO2 at $51 per ton, while it works to develop a new official estimate. Even if their estimate comes in higher than the tentative setting, it may be considerably lower than what the DEC estimates.

Even the DEC’s own estimates diverge dependent on the discount rate used, and they chose to use only low discount rates that mathematically increase the social cost of CO2 emissions. There is no expert agreement on what discount rate should be used, and if a higher discount rate was used the social cost of CO2 would be much lower, and therefore the benefit from eliminating it would be much lower.

While it’s not impossible that the DEC has underestimated the social cost of carbon – which would make the benefits of the CLCPA even larger than estimated – it’s at least as, if not more, likely that they’ve overestimated the social cost for political reasons, meaning the benefits could be far lower than predicted.

The primary driver of the benefits is the social cost of carbon and Hanley’s description of these issues is spot on. There are other issues associated with social cost of carbon that I discussed in my Draft Scoping Plan comments. The biggest inaccuracy is that it is inappropriate to claim social cost of carbon benefits of an annual reduction of a ton of greenhouse gas over any lifetime or to compare it with avoided emissions. The Value of Carbon guidance incorrectly calculates benefits by applying the value of an emission reduction multiple times. Using that trick and the other manipulations results in New York societal benefits more than 21 times higher than benefits using everybody else’s methodology. When just the over-counting error is corrected, the total societal benefits range between negative $74.5 billion and negative $49.5 billion.

- Some Alleged Benefits Are Dubious

Not all of the claimed benefits in the benefit-cost analysis pass the sniff test. The most dubious of these is the assumption that indoor trip-and-fall hazards will be mitigated while weatherizing homes, producing almost $2 billion in health improvements. But there is no inherent connection between weatherization – replacing old windows adding insulation, sealing drafts – and removing interior trip hazards. It could happen, but to say it will is purely speculative.

Another dubious assumption is that people will walk and bike significantly more, creating a claimed $40 billion health benefit – nearly 10 percent of all estimated benefits. But this requires major reconstruction of cities and reduced suburbanization, all in less than three decades. If that doesn’t happen and people fail to change their behavior, this benefit will be drastically reduced at best, and quite possibly come in at close to zero.

My comments on Scoping Plan benefit claims agreed with these dubious claims and also noted that the if the claims related to air quality improvements were accurate then we should be able to observe improvements due to the sixteen times greater observed air quality improvements than the projected improvements due to the Climate Act. Until their projections are verified, I do not accept their projections.

- Subsidies Will Need to Increase, Creating Deadweight Economic Losses

The Scoping Plan proposes transitioning most homes to heat pumps. Currently the only subsidies are $5,000 for geothermal systems, which is too small an amount to enable moderate- to low-income homeowners to afford them. To accomplish this goal, subsidies will have to increase substantially. Most likely this subsidy will be paid for by increases in utility rates, a de facto tax increase on ratepayers.

But both taxes and subsidies create deadweight economic losses, increasing the cost of the policy in ways that were probably not accounted for in the benefit-cost model.

The loss caused by the subsidy will be at least partially offset by the positive externality of reduced carbon emissions, but how much so is challenging to determine (in part because we don’t know the social cost of CO2). Ultimately, the size of these deadweight costs is unknown – and may remain so – but they are real and potentially significant. - There Is No Focused Benefit-Cost Analysis of Individual Projects

The benefit-cost analysis is a global analysis of the whole Climate Act, produced before the consultants even knew what specific policies would be proposed. None of the individual policies proposed have received a focused benefit-cost analysis.

Even getting those right might be challenging, given that so many of these individual projects are megaprojects all on their own. But by focusing on specific policies, there is at least a better chance of achieving accuracy.

An example of a missed opportunity is the requirement that all school districts shift to electric school buses. This will cost at least $8 – $15 billion – a broad estimate that needs to be narrowed down – but the value of the benefits is unknown. While benefits such as reductions in air pollution and improvements in student health are real, we have no dollar amount estimate of them.

We do know that much of the benefit could be gained less expensively by shifting to clean fuel vehicles or buying newer – cleaner burning – diesel buses. Which of these approaches would provide the best benefit to cost ratio, making for the best use of taxpayer dollars? We don’t know because no analysis was conducted before creating the policy.

Conclusion

Perhaps not all these problems will come to pass. Inflation could moderate and remain low. Business flight and avoidance of New York due to cap-and-invest might be reduced if other states join a regional plan. Supply chain challenges for battery materials might be overcome. But others are sure to play a role, such as unionization of green jobs, the effect of the Jones Act, and the deadweight economic loss from subsidies and taxation. In addition, there could be other issues not addressed here that could cause CLCPA costs to increase. This is not intended to be a complete list.

For these reasons, as well as the dismal history of such gigantic public ventures, it’s virtually certain that at least some, if not most, of the individual megaprojects within the CLCPA will be over budget. By how much is anyone’s guess, but it takes an unwarranted leap of faith to be confident that this time will be different. And as noted above, all it would take is for the cumulative effect of budget overruns to push the CLCPA’s cost up by half – a far better performance than most megaprojects – to completely wipe out any gains.

When the fact that the Scoping Plan costs do not include the “already implemented” programs are considered this analysis is overly optimistic. Even without considering all the problems described in this analysis the total costs of all the programs necessart to meet the net-zero by 2050 target are greater than the alleged and impossibly optimistic benefits cited in the Scoping Plan. Any claims that the costs of inaction are greater than the costs of inaction by proponents of the Climate Act are simply wrong.